Although most people know Japanese soldiers invaded Alaska during World War II, most do not know Germany sent two groups of saboteurs to wreak havoc on utilities and industry on American soil.

These men sailed aboard U-boat submarines across the Atlantic, well trained, well equipped, but without any true heart and fervor for the mass destruction they had been sent to accomplish. The title Operation Pastorius was given in honor of a noted German, who settled in America.

Each of the operatives chosen to participate had immigrated to the United States after World War I. Several obtained American citizenship and all were well acquainted with the U.S.A. However, as the Third Reich appeared to be bringing Germany to its former glory, the men took advantage of an offer from Germany to have their passage paid to return to the fatherland. These men were picked from the records of the Ausland Institute, the financial backer of the thousands of German expatriates who returned to Germany.

They were considered to be loyal to the Nazi party, as most had participated in the German-American Bund, an organization that promoted the “New Germany” in America. Understandably, it dissolved and disappeared in 1941. Burger was a member of the original Nazi movement, having fought with Hitler’s attempted coup in 1923. Upon his return to Germany, he rejoined the Party and became the aide-de-camp to the Chief of the Storm Troopers.

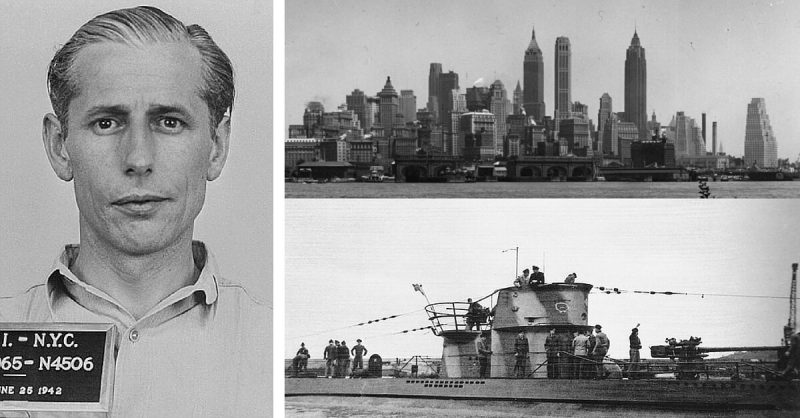

Somewhere along that undoubtedly miserable journey of 3000 miles over fifteen days in a U-boat, the leader of one of the groups of four evidently had second thoughts. George John Dasch, 39, was a smooth-talking former waiter whose mother was the principal reason for his moving back to Germany. Theories exist that he saw the operation as a way to get back to America.

He did arrive in America. Exiting U-202 as it grounded onto Long Island near East Hampton, New York, Dasch and the group loaded boxes of explosives, uniforms and clothing, and over $70,000 in cash into a rubber raft and paddled to shore. Their plan was to bury the boxes and return to them as needed for the various operations. Their objective was to destroy the hydroelectric plants at Niagara Falls, the Aluminum Company of America factories in Illinois, New York, and Tennessee, as well as various locks along the Ohio River to further disrupt electricity generation.

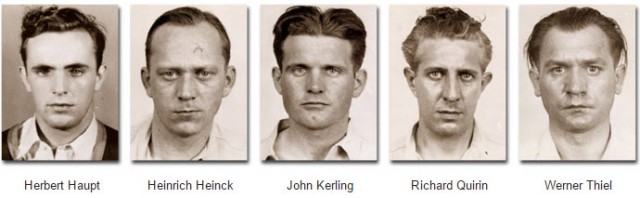

The other team, headed by Edward Kerling, 32, traveled in U-584 to a beach near Jacksonville, Florida. With identical equipment and funds, that group successfully buried their boxes, hopped on a Greyhound bus, and made their way to Cincinnati, Ohio to rendezvous with Dasch’s group on July 4.

The team on a very foggy Long Island beach, however, hit a snag. A young Coast Guardsman patrolling the area hurried toward the men waving a flashlight. Dasch rushed forward to stop him short of where the men were digging. Having already changed out of his uniform, Dasch explained they were stranded fishermen, but had no identification or fishing permit so could not go to the Coast Guard station.

The second in command, Ernest Burger, approached out of the fog speaking in German. Dasch ordered him to go away, causing the Guardsman to become even more suspicious. Then Dasch did something very odd. He grabbed the young man’s flashlight and shined it into his own face. He told the Guardsman he did not want to have to kill him, offered him a bribe and told the young man to remember his face, as he would see it again. The Guardsman took the money and ran away as fast as he could toward the station.

The team hurriedly buried their equipment, changed their clothes and exited the area just before Seaman 2nd Class John Cullen and others returned to the beach bearing weapons.

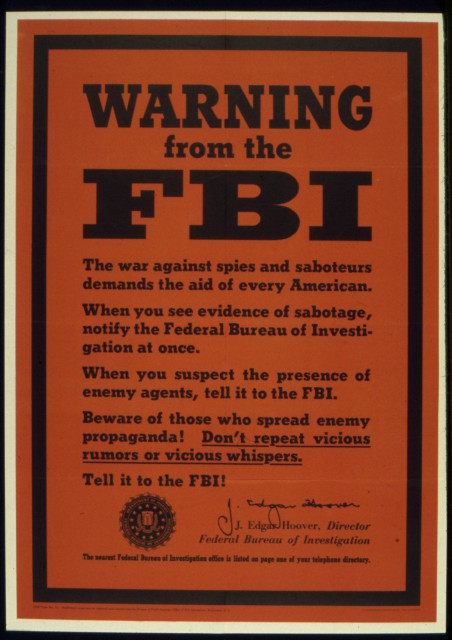

Through a break in the fog, they saw the departing submarine and the freshly dug holes in the sand. Just a bit of digging revealed the boxes with munitions and the discarded German uniforms. The Guardsmen immediately reported the incident, and news quickly reached the FBI. Director J. Edgar Hoover, wishing to keep the arrival of German soldiers on American soil from the press and even President Roosevelt, quietly ordered the largest manhunt the Bureau had seen since the search for John Dillinger.

Meanwhile, the German team of Dasch and Burger made their way to loyal contacts whose information had been written on disposable napkins. At some point, Dasch revealed his plan to scrap the mission and contact the FBI. Undoubtedly, Burger was taken aback, having been a loyal Nazi and willing to spread destruction throughout America.

He was placed in the position of either killing Dasch and taking over the mission, or going along with the leader’s plan. Though Burger was a fierce fighter, he was not a killer.

However, Dasch was apprehensive about calling the FBI. During the training in Germany, the teams had been assured there was no danger from the Bureau, as spies had breached their ranks and were in high positions. Despite his misgivings, he called the New York City FBI office. He was convinced they would hail him as a hero, and he would be able to speak directly with Hoover.

However, the agent who took the call was very skeptical, though he had heard of the incident on Long Island. He advised Dasch he could not connect him with the director. Spooked, Dasch said he would call back in a few days and hung up the phone.

Over the next several days, the team leader worked up his courage to go to Washington D.C. Strangely; he hooked up with some old friends and played pinochle for two days straight. Then he went to Washington. After checking into the Mayflower Hotel, he called the FBI and again asked to speak with Hoover.

The agent, sure it was a crank call, thought it best to send an agent to pick up the man at the Hotel. In his book entitled, “Eight Spies Against America,” (no longer in print) Dasch relates how he was shuffled from office to office facing the same questions over and over until he opened the satchel and dumped about $84,000 in cash on a desk.

That got some attention. The lead agent of the newly organized spy organization team interrogated Dasch for thirteen hours. A 250-page transcript was produced. Even before he had finished telling his story, agents apprehended Burger and were looking for the others. Within days, all the saboteurs were taken into custody, and a report was released to the president.

Brought before a military tribunal of seven generals, the eight German agents were tried and convicted. Dasch and Burger received life sentences. The other six, Edward John Kerling, Heinrich Harm Heinck, Richard Quirin, Werner Thiel, Hermann Otto Neubauer, and Herbert Hans Haupt (who had landed in Florida to meet with Dasch and Burger), were promptly electrocuted, the required sentence for spies.

In 1948, the two incarcerated members of the sabotage teams were granted clemency by President Truman and deported to Germany. Sadly, they were widely condemned for causing the deaths of the others.

Dasch published the book in 1959, then disappeared from the public and died in 1992.

By Elaine Fields Smith for War History Online