Tanks came into their own in WWI and eventually developed into a host of modern fighting vehicles. However, tanks were not the only motorized vehicles to play a part in that war.

The State of Play in 1914

In the early twentieth century, inventors and manufacturers had tried to interest the military authorities in motor vehicles. The internal combustion engine was becoming increasingly popular in farming, haulage, and personal transport. Surely there must be a use for it in the military?

The result was a slightly random selection of vehicles. Some had been enthusiastically obtained and then left to gather dust or became outdated. Others were experimental vehicles used to prove points by their designers, not production models or reliable war machines.

When the armies went to war, motor vehicles, therefore, played little part. Cavalry was considered perfect for scouting. Marching was good enough for infantry. Taxis across Paris were rushed into service to take soldiers to the Marne. However, the lesson learned was that the troops should have been there already, not that motor transport might get men into action more quickly and without tiring them out.

Bring on the Trucks

There were plans in place to use trucks for supplies, and when the war was declared, they went into effect. Subsidy schemes were used to obtain around 1,000 trucks for the British Army and around 1,500 for the French Army. The Germans, with their focus on swift movement to achieve a strategic victory, utilized trucks. Between subsidies and impressment, they pulled together around 30,000 vehicles.

Stalemate on the Western Front turned a vast swathe of the war into a massive siege operation. In those conditions, both sides got a better view of what trucks could do for them. They provided better traction than horses for dragging heavy equipment and supplies around the countryside. Specialist vehicles could perform a range of roles, from ambulances to mobile workshops to gun carriages to petrol tankers.

Austria and Germany, with many of their trade routes cut off by the war, relied upon manufacturers to provide them with their vehicles. The British and French developed their own and also imported vehicles from America.

Armoured Cars

The first combat vehicles were armored cars.

As German troops advanced into Belgium, Belgian officers added boiler-plate and machine-guns to a selection of Minerva and SAVA touring cars. They had some success in holding up the German cavalry.

The British started using armored cars when the Royal Naval Air Service was working around Ostend in the fall of 1914. Eighteen ordinary cars were used to retrieve pilots of downed planes. When the cars came under fire, they began to be fitted with armored plates.

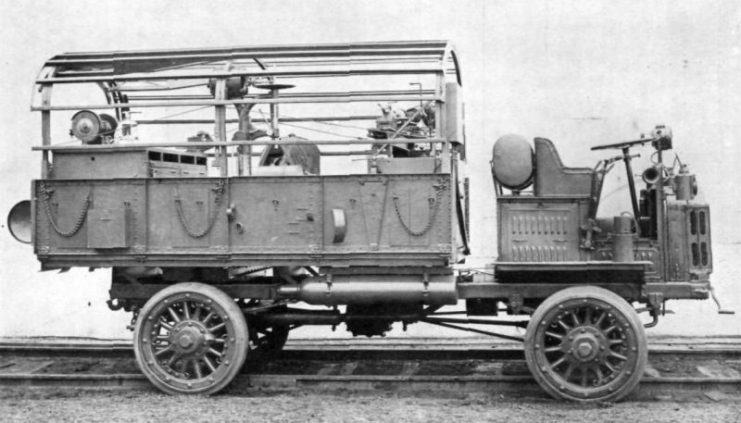

In September, Winston Churchill authorized the creation of 100 armored cars carrying machine-guns. Experiments with fitting vehicles out near the front lines proved it would be better to custom-build them. Various car chassis were obtained, and a standard model of armored car was built around them. Armored trucks followed, carrying crews of ten men and old Hotchkiss three-pounder naval guns to provide support for the armored cars.

As the war in France and Belgium ground to a standstill, the armored vehicles became less useful. They were transferred to other fronts where the war was more mobile, including South West Africa, Mesopotamia, and Russia.

Motorbikes

Motorbikes proved useful, fulfilling different roles to those of trucks and armored cars.

One of their greatest uses was in maintaining lines of communication. Motorcycle couriers provided fast transport for messages and so became somewhat commonplace.

Motorbikes with sidecars were useful for ferrying officers from one place to another. Female auxiliaries were among those who got behind the handlebars, helping to move British officers around.

In the right conditions, motorbikes could be used to improve the mobility of machine-guns. Attached to the side or rear of a bike, the heavy weapons could quickly be moved around the front while remaining ready for action.

Tractors

Heavy artillery was integral to the war and tractors provided ideal vehicles for transporting it. They were designed for heavy labor, fitted to drag equipment around, and could move in conditions that might bog down other vehicles.

The Schneider company, acting as agents for the sale of Holt tractors, made a specialty of selling them to the French army for towing guns. Trying to expand on their use, they experimented with adding armor and weapons to make the tractor into a fighting machine. The first demonstration of one took place in December 1915.

In the same month, the French Colonel Estienne, having seen Holt tractors towing artillery, wrote to General Joffre to suggest a tractor-based fighting vehicle. When Renault was uninterested in the project, Estienne went to Schneider, learned about their experiments, and teamed up with them. Work began on what became the first French battle tanks.

Tanks

Meanwhile, the British had been working in secret throughout 1915 on a new armored fighting vehicle. The landship – which earned the name tank after being disguised as a tanker for liquid – was the brainchild of a group of British officers, engineers, and politicians.

The aim of the innovators was to create a vehicle that could cross the barbed wire and trenches of no man’s land and so break the stalemate of the war. After much experimentation, the designers settled on a simple rhomboid shape with tracks running around the outside. The first tank moved under its own power in January 1916, and the following month it was officially unveiled to a select and secret group of officials.

On September 13, 1916, after much work in manufacturing and shipping, tanks entered the war. Their arrival sent shockwaves through their opponents. It led to every nation working to create similar armored vehicles, but they were far from being the first motor vehicles of the war.

Sources:

Ian V. Hogg and John Weeks (1980), The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Military Vehicles

William Weir (2006), 50 Weapons that Changed Warfare