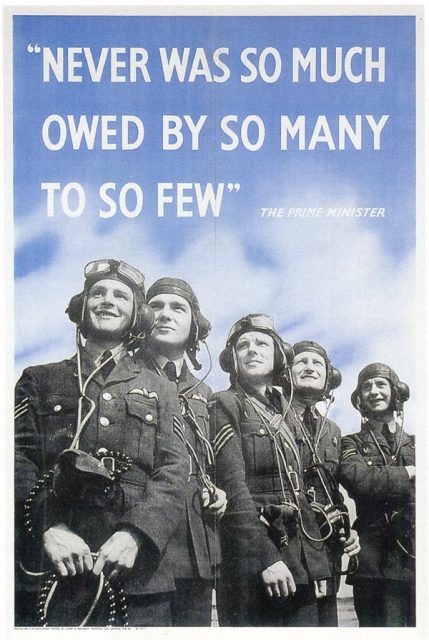

“Never in the field of human conflict has so much been owed by so many to so few.” This famous statement, from a speech by Sir Winston Churchill, commended the pilots of Great Britain’s Royal Air Force (RAF) for their heroic work in defending the British Isles against the German Air Force (Luftwaffe) during the Battle of Britain in World War II.

At the start of the battle, the numerical odds were in favor of the Germans. The Luftwaffe had 1,089 fighters and 1,576 bombers for its offense against the British, while the RAF could only muster around 700 fighters in defense.

However, the British pilots did not bear the brunt of defending their homeland entirely alone. The RAF distinguishes 2,937 pilots as having officially taken part in the Battle of Britain by flying at least one operational sortie between July 10 and October 31, 1940; of this number, 595 were foreign pilots from 13 other nations, thus comprising 20% of the RAF’s pilots.

The New York Times noted, “It is true, of course, that most of the time the British must carry the ball; but just the same these other fellows are doing some pretty good blocking and tackling.”

Why would foreign pilots seek to join the RAF to help the British fight the Luftwaffe in the Battle of Britain? The answer varies, depending on whether the question is asked of the exiled, Commonwealth, or American pilots.

Exiled pilots from Nazi-occupied European nations (Belgium, Czechoslovakia, France, and Poland) sought revenge and correctly reasoned that once the German advance was halted, the turning point would be reached in which they could then begin fighting to take back their own countries.

Commonwealth pilots came to England because they perceived that the present threat to Britain was simultaneously a threat to themselves; as British Dominions, they would certainly be claimed by the Nazis if Germany won the war. Better to fight the Luftwaffe over British skies instead of waiting for the Nazis to appear in their own countries!

A handful of American pilots came to England for a variety of reasons, whether that was for adventure or more altruistic motives such as that described by Arthur Donahue, who recorded his experiences with the RAF in a book entitled Tally-Ho! Yankee in a Spitfire.

He explained, “I felt that this was America’s war as much as England’s because America was part of the world, which Hitler and his minions were so plainly out to conquer.”

All the foreign pilots were welcome additions to the RAF because they had already acquired flying skills in their countries of origin; as The Times observed, “Aeroplanes may be mass produced, but there is no shortcut in training pilots, observers, and gunners.”

Though the British worked hard to quickly train more pilots, by the end of September 1940 only five of the new squadrons could be added to the operational strength of Fighter Command.

One of these was No. 1 Squadron of the Royal Canadian Air Force. The other four were flown by the heroic remnants of the air forces of Poland and Czechoslovakia. Of the exiled European pilots, the Belgians and French were integrated into British squadrons, but there were so many Poles and Czechs that each nationality had two of its own squadrons within the RAF, as well as men scattered throughout other British squadrons.

The Polish and Czech pilots became famous for the number of German aircraft they shot down. In one story the New York Times related how one of the Czech squadrons had shot down nine Germans one day and seven another day, and added, “The actions of these men is [sic] being praised widely [in Britain] where fighter pilots of any nationality can be used.”

One of the greatest aces of the Battle of Britain was Czech pilot Josef Frantisek, whose career total of 28 enemy planes destroyed included 17 shot down during the Battle of Britain. The Polish were considered the most remarkable of the RAF’s foreign pilots. Their lack of fear for their own lives led them to take great risks from which they usually emerged unscathed, because, as Arthur Donahue observed, “They fought savagely, for their pilots had nothing to lose.”

The renowned all-Polish 303 Squadron shot down over 100 Germans in one month alone. A Canadian pilot wrote, “They introduced their own technique in air fighting. They sailed right into the enemy, holding their fire until the very last moment. That was how they saved their ammunition and how they got so many enemies down with each sortie.”

Perhaps a British pilot, H. A. Fenton, provided the best description of the British pilots’ regard for their allied brothers: “The Poles and Czechs (of blessed memory) were vital as it turned out…. It was amazing how quickly we became real friends. I flew with a Pole on one side and a Czech on the other and was delighted to be so well looked after.”

The pilots from the British Empire and Commonwealth also made important contributions to the RAF. Canada transferred an entire squadron of its own air force—complete with planes—for Britain’s defense, but several other Dominions contributed valuable manpower. New Zealand sent more pilots (127) than any other Dominion, followed by Canada (113), South Africa (25), and Australia (32).

The Irish contributed 10 pilots, and there were even 3 pilots from Rhodesia, 1 from Jamaica, and 1 from Barbados. Many of the Commonwealth pilots were utilized in leadership and training positions. The famous Polish 303 Squadron was initially commanded by Johnny Kent, a Canadian. Another Canadian, “Butch” Barton, took charge of 249 Squadron; an Australian pilot there recalled, “I and the rest of 249 would have followed ‘Butch’ anywhere.”

A South African pilot, A. G. “Sailor” Malan, led 74 Squadron, and “his fellow ace, Alan Deere, reckoned that Malan was the finest shot he had ever seen.”

In addition to both the exiled and Commonwealth pilots, 9 Americans joined the ranks of the RAF pilots to fight the Battle of Britain. One trio of Americans—Eugene Tobin, Andrew Mamedoff, and Vernon Keogh—that served well in 609 Squadron, originally “had come over to help the Finns fight the Russians in 1939, switched to France when the Finns surrendered and [later] made their way across the Channel to what they saw as the last island bastion of freedom in Europe.”

Another American, William Fiske, was a former Olympic bobsled ace who proved to be as successful in flying a Hurricane fighter as he had been at guiding a bobsled. Before he was killed on August 17, the popular young pilot was credited with destroying several German planes.

Arthur Donahue, the sole American in his squadron, was frequently asked if the United States was going to give Great Britain any help; his typical response was “I don’t know. They’ve sent me, haven’t they?” While the Americans did not have an enormous impact – simply because there were only 9 of them – any amount of help, no matter how small, was welcomed by the RAF.

By the end of October 1940, the Battle of Britain was over. The exiled, Commonwealth, and American pilots who flew with the RAF helped attain the British victory by bringing their skills to the RAF when Great Britain needed them most.

They fought successfully, shooting down German aircraft out of proportion to their own numbers. “Not many but much” was the motto of the all-Czech 312 Squadron, and these words are a fitting description for all the foreign pilots who helped Great Britain defeat Germany’s Luftwaffe against all odds in the Battle of Britain.