Tunneling through walls, or through cement flooring. Dissolving metal bars with salsa, or the rough end of a nail file. A simple, quick slip through an accidentally opened window. Prison escapes and their masterminds are always creative, the stories both incredible and unbelievable.

How is it possible that men could slip out of sight, out of the confines of their cells or restraints, unnoticed by anyone? Almost magical, and indeed mysterious, a successful prison break becomes a bit of lore – and countless other prisoners use them as inspiration when they, too, wish to break beyond the bars of their confinement.

Such is the case with the Great Papago Escape. Under the cover of a wintery night in 1944, a group of 25 men escaped from a prison camp in Phoenix, Arizona, while the Allied Forces and Germany fought World War II an ocean and a nation away.

However, this prison escape was not like those in prisons around the world – it was one led by Nazi prisoners of war, by a man known as a “Super Nazi” by American military officials. This prison break, now known as the Great Papago Escape, was the most significant escape by Axis prisoners of war to take place during the war.

A Notorious Prisoner Begins Planning

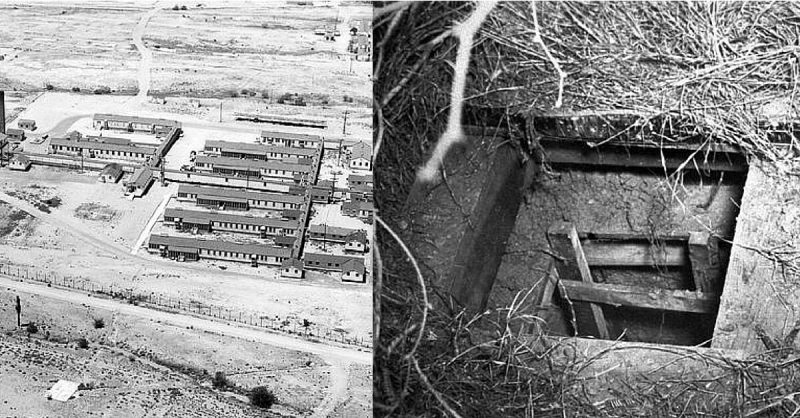

In 1943, the American military built Camp Papago Park in Phoenix, Arizona. Initially known as Papago Park, the site was designed and used as a recreational area for the city’s residents. However, with the onset of World War II, Papago Park was turned into a camp at which to keep Italian prisoners of war.

In January of 1944, the camp’s purpose changed: it became designated as a camp for Germans instead. Many of those who spent time at Camp Papago were members of the Kriegsmarine.

Camp Papago was like so many other prisoner-of-war imprisonment camps throughout America and other nations. Surrounded and enclosed by barbed wire fences and watchtowers, its residents stayed in one of five compounds on the grounds – one for officers only, and the rest for other soldiers.

Approximately 370 U.S. guards and officers watched over the Germans. However, Camp Papago was somewhat unusual in that none of its prisoners were required to work in any manner. Traditionally, prisoners were put to work to stave off boredom; at Papago, the men chose whether or not they wanted to volunteer at nearby workplaces like cotton fields.

During its peak years, Camp Papago interred about 3,100 German prisoners, many of whom were U-boat sailors. One of these men was quite well-known: Captain Jürgen Wattenberg, the highest-ranking German official in the camp. Wattenberg was the commander of U-162, a ship sunk near the Bahamas in September 1942 by the British Royal Navy.

The British, fearful that keeping Wattenberg in their care would lead to problems, passed him and his crew along to the United States. Considered a “Super Nazi” who caused trouble in every prison he spent time in, no nation wanted the responsibility of imprisoning Wattenberg; after being passed from camp to camp, he finally landed at Papago.

Although American military officials believed Wattenberg could do no harm in the barren Arizona desert, the commander of Camp Papago made one serious oversight: all of the camp’s most problematic, most escape-prone soldiers were kept together in the officer’s compound. Rather than separating these dangerous men from one another, they were instead sharing each other’s company.

Wattenberg, of course, began plotting his escape as soon as he took up residence in camp. He discovered that the officer’s compound featured a very fortunate blind spot – there was one area of the building that the guard towers couldn’t see, one small section hidden from all sight. That was the spot in which Wattenberg decided to begin constructing an escape tunnel.

The Tunnel Grows

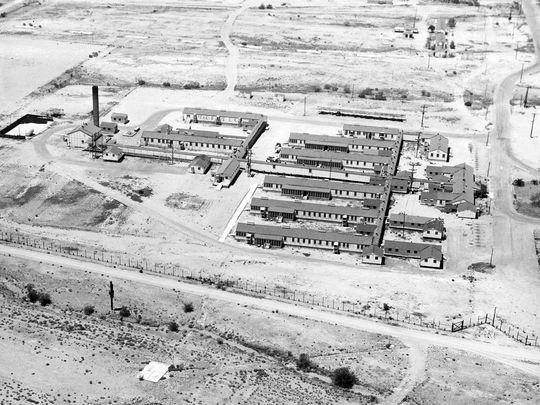

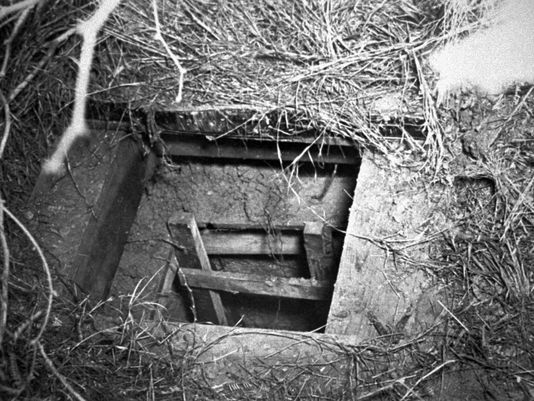

With no tasks or work to complete and some German masterminds at his employ, Wattenberg had the perfect storm of luck. Immediately upon determining where he would create his escape tunnel, he and his fellow prisoners got to work. The blind spot provided by the officer’s compound also happened to be close to Camp Papago’s bathhouse, where the men showered – and this was the closest building to the camp’s eastern perimeter, so the men could tunnel from inside the bathhouse, underneath its barbed-wire fence, and out into freedom.

Whenever Wattenberg and his men visited the bathhouse under the pretense of showering, they instead worked on their ingenious tunnel. Hidden beneath a box of coal was the Germans’ tunnel entrance; they pushed the box aside, removed a section of the wooden wallboards, and slide into the tunnel to continue working.

The tools to complete the task were readily available – in fact, American officers and guards were more than willing to give Wattenberg and his men shovels and rakes. Wattenberg simply told the Americans that he and his men were constructing a volleyball field at the compound.

Wattenberg organized his men to dig effectively and efficiently. Sticking to a schedule of three-man shifts, each group of Germans worked for 90 minutes at a time every night. As they removed the rocky Arizona soil, the men flushed the dirt down toilets, hid it in locations around the camp, and even down the legs of their pant legs. As the tunnel grew, they even began hiding the excess dirt in plain sight – right on the volleyball field, the Germans claimed to be building.

American guards never noticed all of this extra dirt. Though they began the tunnel in September 1944, their efforts grew it quickly; by December 20 of that same year, it measured 178 feet (54 meters) in length, which reached from the bathhouse to the Cross Cut Canal beyond Camp Papago’s borders.

Once the tunnel was ready for use, Wattenberg began preparing post-escape plans to get his men back to Germany. He successfully arranged for clothing, fake identification documents, and even contacts in Mexico for all 25 men. The rest of the Germans in Camp Papago’s other compounds were also helping the officer’s compound escape; they planned to throw a loud, raucous celebration on the night of the escape in hopes of distracting the guards.

But Wattenberg wanted to ensure that he and his men could gain much ground upon their escape. If the Americans realized their absence quickly, they would more easily recapture the Germans. So, Wattenberg decided to excuse himself and his men from roll call – he had four U-boat captains tell American officer that German officers wouldn’t appear for roll call. This set off a 16-day prisoner strike until a compromise was reached: German officers were excused from Sunday morning roll call.

Wattenberg’s Success – and Ultimately, Failure

With roll call altered, the tunnel completed, and post-escape plans prepared, Wattenberg and his men were ready to make a break for their freedom on Saturday, December 23. At 9:00 on the evening of that Saturday, Wattenberg, and 24 fellow German officers successfully walked through their handmade tunnel and into the Arizona desert, free from Camp Papago by 2:30 in the morning on December 24. The men divided into small groups, and walked away from camp, purposely avoiding any form of public transportation.

However, Wattenberg’s luck turned by 7:00 PM that day. One American officer, Captain Parshall, noticed that some of Camp Papago’s prisoners were missing. Just a few hours later, American soldiers, FBI agents, and even Papago Indian Scouts mobilized for what became known as the greatest manhunt in Arizona’s history.

Luckily for these skilled search teams, the prisoners faced obstacles that led them to be recaptured quickly: they were hungry, freezing in the cold, wet weather, and confused by Arizona’s desert landscape. Only a few of the Germans attempted to evade escape for weeks. By January 8, all of the men were recaptured before reaching the Mexican-U.S. border. Only three holdouts remained – Wittenberg and two others.

From there they explored the area and even dared to venture into the city. According to author Ronald H. Bailey, Kremler “pulled off the most bizarre caper of the entire escape.” Every few days he would make contact with one of the German workers sent outside of the camp’s perimeter and exchange places with him.

The exchanged prisoner would spend the night in the cave with Captain Wattenberg while Kremer slipped back into camp. Inside, Kremer would gather food and information. To deliver the food he would either join a work detail and escape again or send it out with another worker. This continued for some time until January 22, when a surprise inspection revealed Kremer’s presence in camp. Kremer must have given his captors information because on the following night Kozur was captured by three soldiers at the abandoned car used to hide the provisions.

They quickly captured the other escaped prisoner hiding with him; Wattenberg then chose to head into the city of Phoenix, where he ate at a restaurant, slept in a hotel lobby, and then ran into a street cleaning crew once night fell. After speaking with one member of the street cleaning crew, Wattenberg’s fate was sealed – finding his accent odd, the street cleaner notified the police. By 9:00 AM the following day, American officials had Wattenberg in custody once again.

With all of the escaped Germans safely back in imprisonment, the men expected to be punished for their actions. The Germans had a history of executing Allied prisoners of war, and Wattenberg and his men assumed their fate would be the same. However, the Americans did no such thing; they simply reduced the men’s rations to bread and water for a period of time. The war continued, a great distance away, and the prisoners were held until the end of World War II.

Today, little remains of Camp Papago Park and its great escape. The camp has become a site for the Arizona National Guard, and the Arizona Military Museum, in which the story of Wattenberg’s Great Papago Escape lives on in a historical display.