The notorious Nazi Party member, Julius Streicher, wasn’t part of the military nor did he participate in the planning of the Holocaust. Nevertheless, on the early hours of 16th of October, he was hanged, as a consequence of his death sentence.

Why?

Because he was one of the most prominent anti-Semites in all of Nazi Germany. Since the competition was serious those days, you might imagine how hard he had to try.

A veteran of WWI who earned an Iron Cross for his actions, Streicher was involved in a number of political parties after that war. After the Great War, the Weimar Republic was a rift between radical political options. The years following the failed Communist attempt to take over the government in 1918 saw the rise of many far right organizations in Germany, one of them being the NSDAP (The Nazi Party). But before the NSDAP there was the German Worker’s Party, and Streicher was one of its first members.

He founded the local branch of the Party in Nuremberg, where he lived with his wife. Streicher soon began to practice his early adopted anti-Semitism, since he claimed that his political work brought him into contact with German Jews, and he “must, therefore, have been fated to become later on a writer and speaker on racial politics.”

Through the German Worker’s Party Streicher got familiar with the works of editors and journalists who were contributing to the The Völkischer Beobachter (People’s Observer) newspaper, which was the early voice of the Nazis.

But his feverish anti-Semitism didn’t get a positive response in the German Worker’s Party. He left the organization and founded his own, leading his substantial following with him.

After hearing a three-hour long speech in Munich, Streicher became infatuated with Adolf Hitler, who was becoming more and more popular during the early 1920s. Immediately he suggested Hitler to merge his fraction of the Worker’s Party with Hitlers’s NSDAP, thus bringing in new members.

In 1923, Streicher founded Der Sturmmer (The Attacker) where he could freely agitate against the Jews in Germany, with support from Hitler. The newspapers which functioned on a mixture of panic-inducing tabloid articles and slander famously announced in their first headline: “We Will Be Slaves of the Jew; therefore He Must Go!”

Streicher became very close to Hitler, and during the failed Beerhall Putsch in November 1923, he was right next to the would-be dictator, marching and facing the Bavarian police. His loyalty shown by this act earned him Hitler’s lifelong trust and protection, and in the years to come, Streicher was one of the few that could’ve considered themselves to be the tyrant’s intimate friends.

In 1925, when the Nazi Party was reorganized after being banned for two years as a result of the failed coup attempt, Julius Streicher was appointed Gauleiter of the region Franconia (which included his home town of Nuremberg). The Gauleiter was a Party official with very symbolic powers, but once the Nazis took over the government in 1933, Streicher’s position was far less symbolic and far more actual. The Gauleiters like Streicher were practically untouchable by the legal authority during the 12-year long rule of the Nazi Party. Streicher was also elected to the Bavarian “Landtag” or legislature, a position which gave him a margin of parliamentary immunity – a safety net that would help him resist efforts to silence his racist message.

Meanwhile, The Sturmer was printing more copies than ever. Streicher and his mouthpiece for anti-Semitism started targeting notable Jews in smear campaigns. He would lure a person into a lawsuit by accusing them of some idiotic slander, then follow the trial with press coverage. Even though Streicher would lose the case, he would garner the attention through a detailed testimony which would expose some other not-so-glorious, but still trivial, facts about the accused.

This was the case with the Nuremberg city official Julius Fleischmann, who was accused by Streicher in 1924 of stealing socks from his quartermaster during combat in World War I. Even though Fleischmann won the case, his reputation was badly damaged. This was how Streicher discredited people through his newspapers. But it wasn’t all about discrediting Jews; it was also about getting his message heard throughout Germany. Other newspapers of the time wrote about the trials as well, causing a sort of sensation of the court being turned into a ridiculous arena for gossip and slander.

The Sturmer’s infamous slogan “The Jews are Our Misfortune” was soon becoming more and more adopted among the ethnic German population.

Streicher began reviving old anti-Semitic myths, like the one dating from medieval times that claimed that the Jews committed ritual murders and that they used blood from Christians for the preparation of Matzo, an unleavened flatbread used for Jewish holidays.

He insisted in the pages of his newspaper that the Jews had caused the worldwide Depression, and were responsible for the crippling unemployment and inflation which afflicted Germany during the 1920s. He claimed that Jews were white-slavers and were responsible for over 90 percent of the prostitutes in the country.

Streicher’s favorite misguidance in the newspapers was the idea that German wives were cheating on their husbands with Jews, or even worse, that Jews were raping German women. This gave him the opportunity write obscenities and publish pornographic images; that in particular gave the younger male audience an appeal. He certainly knew that sex sells.

In 1933, after the Nazis took power, Streicher called for a boycott of all Jewish-held businesses and imposed a series of anti-Semitic commercial measures. He had his fingers everywhere: from fueling the anti-Semitic propaganda together with Goebells to writing forgeries from the Old Testament and the Talmud in which he claimed that the Jewish religion takes an offensive stand against the Christian civilization. Streicher even published children’s books which promoted anti-Semitism, such as Der Giftpilz (the “the Toadstool” or “the poisonous mushroom”).

He was incredibly bold and used even against his opponents in the Nazi Party. Streicher invented a rumor that Goering’s daughter was conceived using artificial insemination; in response, Goering forbade all members of his staff to read The Sturmer. In 1938, the biggest pre-war persecution of Jews was staged by the Nazi Party. It was called the Kristallnacht. Streicher was known for seizing Jewish property for himself after the massive pogroms started.

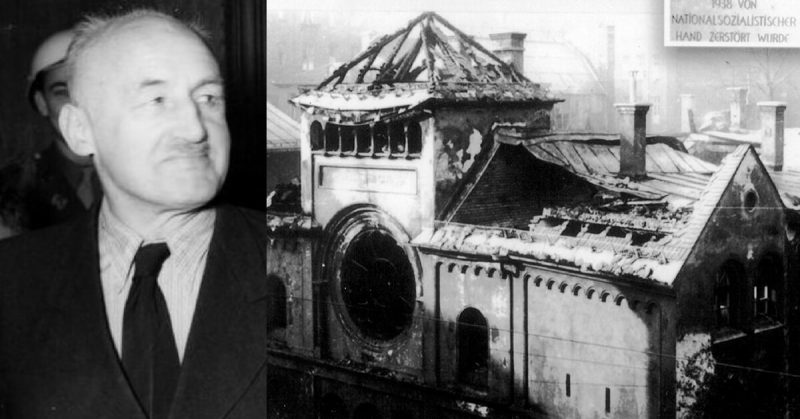

The pinnacle of his arrogance was the order to burn down the Nuremberg synagogue; he later claimed that his decision was based on his disapproval of its architectural design.

Julius Streicher and his campaign of anti-Semitic press prepared the German public for the events of the worst persecution of Jews in history. After the war, he was among the first to be trialed in Nuremberg. The judgment against him read, in part:

For his 25 years of speaking, writing and preaching hatred of the Jews, Streicher was widely known as ‘Jew-Baiter Number One.’ In his speeches and articles, week after week, month after month, he infected the German mind with the virus of anti-Semitism and incited the German people to active persecution. … Streicher’s incitement to murder and extermination at the time when Jews in the East were being killed under the most horrible conditions clearly constitutes persecution on political and racial grounds in connection with war crimes, as defined by the Charter, and constitutes a crime against humanity.

Here is a newsreel reporting about Streicher’s trial at Nuremberg after the war

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rR073nnbbE4