World War II introduced the international community to a host of new horrors: Adolf Hitler’s concentration camps dedicated to death, Japan’s air-led destruction that turned Pearl Harbor into a scene of fiery explosions and death, and bombings that decimated entire cities, monuments, and landscapes throughout Europe.

Yet one of the most unforgettable moments of the war came during its final days. As the Allied Forces accepted Germany’s surrender, attention turned to Japan, the one enemy still standing. The world’s first nuclear bombs brought Japan to its own surrender and showed nations around the world just how deadly a single bomb could be.

Although the United States was responsible for unleashing these new and terrifying weapons, it wasn’t the only nation prepared to use an ultimate means of destruction.

Like the United States in the years and months before the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Japan was also preparing for the possibility of waging an entirely new type of war on its enemies. However, Japan didn’t want to target just any Allied nation – its political and military leaders wanted to strike on U.S. territory yet again, this time on its mainland.

Upon the request of Japan’s Emperor, military experts developed a plan named Operation Cherry Blossoms at Night, a plan that would devastate Southern California with biological warfare. Though the intended operation was never enacted, its development was careful and its intentions severe.

The secrets of Operation Cherry Blossoms at Night detail what might just have happened had World War II come to a different end, one in which Japan was named the victor.

The Plan for Biological Destruction Begins

After Japan’s successful attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941, war was no longer a possibility; it was a certainty, and it was one that Japan eagerly anticipated. The nation, its leaders, and its military were all prepared to wage war on the United States – and biological warfare was at the heart of those plans. In the months that followed Pearl Harbor, the Japanese began readying different plans for biological-based attacks meant to cripple the U.S. population.

As Japanese troops took to the battlefield against American forces, military leaders had prepared biological attacks for any scenario. Japan was not a nation afraid of striking the enemy’s health. In March of 1942, as the Battle of Bataan raged on, Japanese forces were ready to unleash 200 pounds of plague-ridden fleas in 10 different attacks on U.S. soldiers.

The American troops surrendered at Bataan, and the fleas were never used. Two years later, in July 1944, the Japanese again readied the exact same biological weapon during the Battle of Saipan. Fortunately for the U.S. forces, the fleas were killed on their way to the battlefield when the American submarine Swordfish sank a Japanese submarine. The Japanese tried once more to use a biological weapon during the Battle of Iwo Jima, during which the troops were planning to drop pathogens on invading U.S. forces.

One Japanese pilot, Shoichi Matsumoto, recalled that orders were to send two gliders over the invaders and release disease that would shower the American troops – yet once again, this plan failed when the gliders took off and never reached their intended destination.

Though each one was shelved or never succeeded, these planned attacks wouldn’t have been Japan’s first foray into biological warfare. In fact, the Japanese military had relied on biological weaponry years before World War II broke out – the nation had a special military unit named Unit 731 created for and solely devoted to biological and chemical warfare that dated back to the early 1930s.

Unit 731 began its work in Manchukuo when Japan took control of the Chinese state. The Unit was tasked with researching potential biological and chemical weapons, and the effects they would have when unleashed on enemy populations. So, Unit 731 got to work under the leadership of Shirō Ishii, experimenting various diseases and dangerous chemicals on men, women, children, and even infants. The Japanese didn’t just conduct these cruel experiments on captured prisoners or injured enemy soldiers; instead, they ran the potentially deadly tests on anyone they could find.

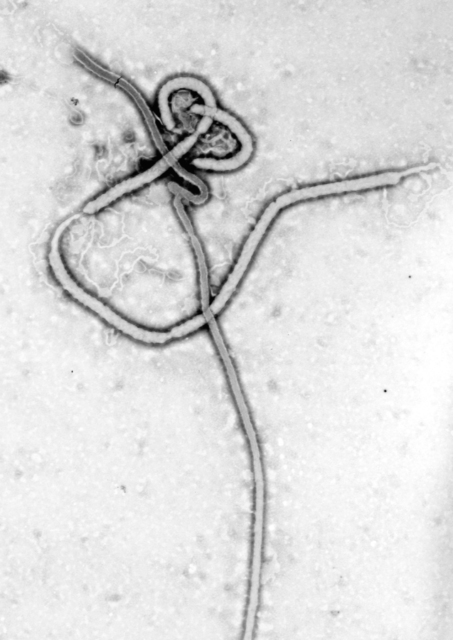

Thanks to the efforts of Unit 731, the Japanese military was quickly ready to put all of the research to use and wreak biological havoc. The Second Sino-Japanese War provided the perfect opportunity: Japanese soldiers placed the bubonic plague, cholera, smallpox, botulism, anthrax, and even more varied, dangerous diseases inside bombs that were meant for use against the Chinese military.

As the war and its conflicts pitted the Japanese and Chinese against one another, Japan unleashed it’s biological weapons – and the effects were deadly. In 2002, researchers estimated the number of Chinese individuals, both in war and during Unit 731’s human experimentation, at approximately 580,000. With this astounding and effective new type of warfare, the Japanese were eager to enact similar damage upon the United States during World War II.

A New Target: The Shores of the U.S.

Of course, the battles Japan faced throughout World War II proved more challenging and riddled with problems, and the opportunities to use biological warfare seemed to fail at every turn. That didn’t deter Japan’s leaders, military experts, or Shirō Ishii himself.

Instead, Ishii took on a new task: as Germany surrendered and Japan prepared to face the full attention of the United States, Ishii was asked to develop a long-distance, large-scale attack that would cripple the enemy nation. Operation Cherry Blossoms at Night was born, and Ishii spent the final months of World War II planning and preparing the details for this intended kamikaze mission.

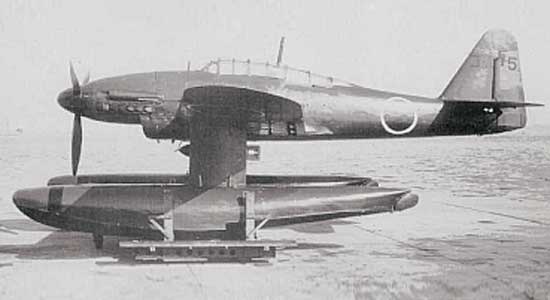

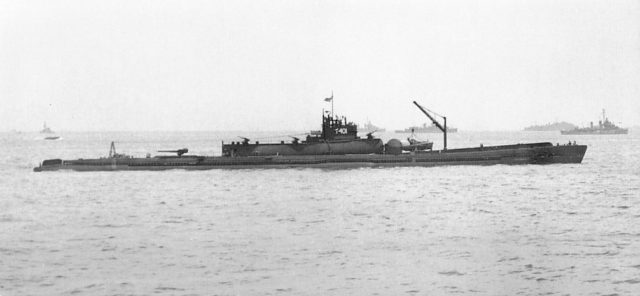

The plan for Operation Cherry Blossoms at Night required submarines, aircraft, and men to man these carriers of biological weapons. The men who would bring the weapons to their final destination weren’t going to survive. On March 25, 1945, Ishii’s operation was finalized. Five I-400 long-range submarines would leave Japan’s shoreline and travel across the Pacific Ocean, with each sub carrying three Aichi M6A Seiran aircraft.

The aircraft onboard the submarines held bombs with plague-carrying fleas, the weapons that would unleash hell in Southern California. Once the submarines got close to San Diego, they would surface and launch their airplanes towards the coastline. While in the air, the planes would drop their flea-filled bombs.

With this done, Operation Cherry Blossoms at Night would be nearly complete – all that would be left was the spread of infection and death through San Diego and beyond. After the bombs detonated and the fleas carried the plague from person to person, household to household, the Japanese expected that tens of thousands of people living in California would die.

The Japanese military approved Ishii’s plans and set a date for the operation: September 22, 1945. Yet misfortune befell Japan’s biological warfare plans once more before World War II drew to a close. Once the operation was announced, the Imperial Japanese Navy decided that the entire plan was far too risky and impractical to carry out.

The Navy wanted to instead devote its efforts to protecting and defending Japan’s nearby islands, and officials didn’t want to potentially lose any of the brand new I-400 submarines for such a mission. Operation Cherry Blossoms at Night was destined never to see the light of day, as Japan surrendered to the United States on August 15 that year.

So, although the Japanese dedicated great effort and research to bringing enemies to their knees with biological destruction, it was an entirely different new breed of weapon that brought World War II and Japan’s grand plans to an end.