Operation Downfall was a planned military operation by the United States and its allies toward the end of the Second World War. The aim was to invade and occupy Japan’s home islands in what would have been one of history’s largest amphibious assaults. It also had the potential to be one of the deadliest military operations ever executed.

Despite the extensive planning that went into it, Operation Downfall was never put into action.

Developing Operation Downfall

After the success of D-Day, it was becoming more and more clear that the war in Europe was going to soon be over. However, for those fighting in the Pacific, peace was still far away.

In early 1945, the Combined Chiefs of Staff met at the Argonaut Conference to come up with a plan to put an end to the fighting once and for all. At the conference, they created the first components of what would become Operation Downfall, the American-led invasion of Japan.

The plan was based on the assumption that the conflict in Europe would be over by July 1, 1945 and that the invasion of Okinawa, which had yet to occur, would be over by the middle of August. Operation Downfall would be split into separate parts, which were intended to take place in November 1945 and at the beginning of ’46, respectively.

The former would use troops already serving in the Pacific, while the latter would see a combination of those men and troops who had been transferred after the fighting in Europe came to an end. The scale was astounding, and the operation would have been a larger amphibious landing than D-Day.

Operation Olympic

The first stage of Downfall, Operation Olympic, was officially scheduled for November 1, 1945. The American forces would use the recently-captured Okinawa as their base while they invaded Kyūshū, which would, in turn, become the area used by future troops during Operation Coronet.

Involved in this half of the operation would be 400 destroyers and their escorts, 24 battleships, 42 aircraft carriers, 14 divisions and two regimental combat teams. A Commonwealth naval fleet of four battleships and 18 aircraft carriers would join them.

The land and sea forces would be aided in both transportation and gaining control of the landing beaches by the Fifth, Seventh and Thirteenth Air Forces. The US Strategic Air Forces in the Pacific (USASTAF), as well as the British Tiger Force, would be charged with strategic bombings. They’d have been joined by the renowned “Dambusters,” No. 617 Squadron of the Royal Air Force (RAF).

Operation Coronet

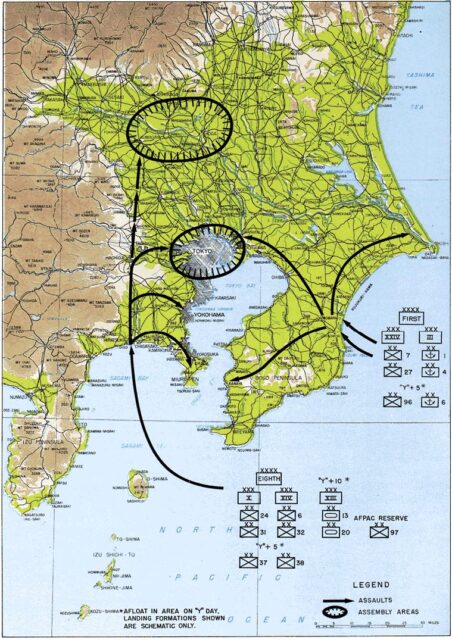

Following the proposed success of Operation Olympic, the Americans planned a secondary invasion. This was designed, in part, to put military pressure on the Japanese capital by invading Honshu.

“Y-Day,” as it was called, was to begin on March 1, 1946, with the deployment of 25 US divisions from the First and Eighth armies landing at Kujūkuri Beach and Hiratsuka, respectively. After the initial landings, another 20 divisions would have been deployed as reinforcements.

The plan was also to have at least five Commonwealth Corps divisions join the Americans at this time. These joint British, Canadian and Australian troops weren’t initially going to be used, but they were incorporated after they were offered to the Americans. They would help the US troops push north to circle the capital, before moving to Nagano.

Operation Downfall’s success would have come at a heavy price

While the Americans created a concrete plan for invading Japan, Operation Downfall would have come at a heavy price. As part of the preparation, they did calculations to see what the estimated casualties would be. While the numbers varied, the outcome was always staggeringly high.

One approach taken by Fleet Adm. William Leahy was that the casualties would be similar in number to those experienced on Okinawa – 35 percent. This meant the invasion of Kyūshū alone would have resulted in 268,000 casualties. This number was similarly echoed by Intelligence Chief Maj. Gen. Charles Willoughby.

Some estimates were far higher. One study conducted during deliberations showed that the invasion of Japan would cause up to four million American casualties and around 10 million Japanese deaths. It was these figures that played a role in the decision to drop the atomic bombs.

Operation Ketsugō

While the US was planning its invasion, Japan was developing its defenses. Officials knew the likelihood of an Allied attack was growing stronger every day and correctly assumed one would happen after the 1945 typhoon season. Impressively, they were also able to accurately predict which areas would be invaded.

They prepared to take on 90 Allied divisions – 20 more than what would have been used. By now, Japan knew they weren’t going to win the war. Instead, officials hoped to make the cost of invasion so high that the Allies would opt for an armistice.

Not only would Operation Ketsugō, Japan’s resistance plan, deploy impressive military numbers, but it would also use civilians. Masses of new troops were trained, including frogmen, as were 28 million men and women for the Volunteer Fighting Corps. Japan also intended to use its infamous kamikaze to help prevent the Allied naval forces from getting anywhere near the shores.

Downfall of Operation Downfall

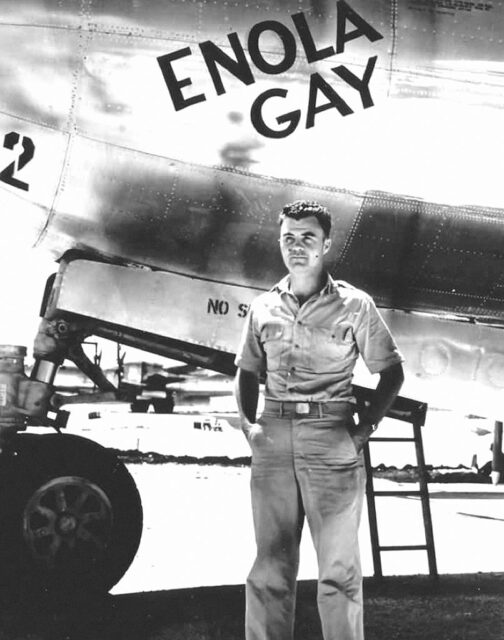

Ultimately, Japan’s preparations were for nothing, as its troops couldn’t withstand the attacks that brought World War II to a close. Before Operation Downfall could be put into action, the Americans dropped the atomic bomb Little Boy on Hiroshima, followed shortly after by Fat Man over Nagasaki. The Japanese surrender and the Soviet advance into Manchuria that followed solidified for the allies that Downfall was no longer needed.

Prior to this, the US really was actually preparing for the invasion. The country even went so far as to create almost 500,000 Purple Hearts in advance of the waves of injured Americans that would come out of Operation Downfall. Since they were never needed, the US military opted to hand out these medals in future wars; so many were made, in fact, that they were given out during the Korean War, in Vietnam, and during the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan.

More from us: The WWII-Era Heroics of the Real-Life Monuments Men

As of 2020, it was believed there could be as many as 60,000 of these Purple Hearts yet to be given out.