In 1944, the British hatched a plan to assassinate Hitler – a project known as Operation Foxley. It could have shortened the war, saved millions of lives, and spared everyone so much pain and suffering. The scheme had the approval of many in the British government, including Winston Churchill, but it was rejected because Hitler was helping the Allied cause.

Attempts to kill Hitler were nothing new with the most famous one being the July Plot. Anti-Nazi conspirators led by Claus von Stauffenberg tried to kill Hitler with a bomb on 20 July 1944. But as early as 8 November 1939, Johann Georg Eiser blew up the Bürgerbräukeller where Hitler gave annual speeches, missing killing Hitler by 5 minutes.

The British had been wanting to get rid of Hitler rather early in the war, but he was clearly not an easy man to kill. There was also the matter of an old world mentality. A number of British officials wanted a “gentlemanly war” – meaning one that was fought along honorable lines. They didn’t approve of espionage, sabotage, and assassination, and were often at loggerheads with those who used such methods.

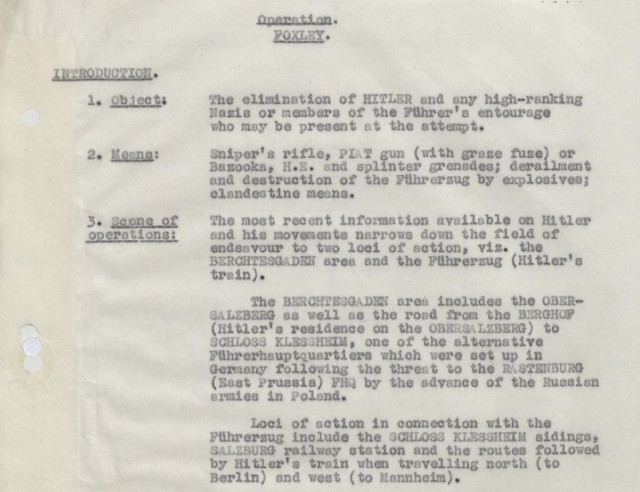

Fortunately, this didn’t stop them making plans to end the Fuhrers life, which is how Operation Foxley was thought up. The British Special Operations Executive (SOE) had inside information on Hitler’s habits because of German POWs and defectors. The original plan called for bombing the “Amerika,” Hitler’s private train, or by poisoning its water supply.

It wasn’t tenable, however. Hitler’s use of the train was both irregular and unpredictable. Stations were usually informed of his arrival only minutes beforehand, making timing impossible. There was also the need for an inside man, which couldn’t be had. So the plan was scrapped, as were further attempts to assassinate the German chancellor.

Things changed, however, after the Normandy landings in France on 6 June 1944. During that battle, one of Hitler’s personal guards was taken prisoner and interrogated. It turned out that he had also served at the Berghof, Hitler’s mountain retreat and home in the Bavarian Alps where he spent much of his time during the war.

The Berghof was part of a larger complex on the Obersaltzberg with several buildings on it, all the high-ranking Nazi’s had houses there. Whenever Hitler was in residence, a Nazi flag was hoisted from the main house and could be seen from a café below in the town of Berchtesgaden.

At a little past 10 AM, Hitler would leave his house and walk to the Mooslanerkopf teahouse within the premises, where he would have breakfast. The jaunt took him between 15 and 20 minutes either way. Because he felt secure within the compound, he preferred to walk alone, except when he was with guests. Other than that, he disliked being accompanied by bodyguards.

But he was protected. The route he took was visible from various sentry posts dotted around the estate, including one from the teahouse. His path ensured that his security forces were never more than 100 to 500 yards away from him.

Allied reconnaissance had taken pictures of the Berghof, so they knew the lay of the land and were able to confirm this route. They, therefore, knew that the Führer’s morning walk took him within several hundred yards of a wooded area just outside the estate.

It was decided that a sniper could hide in that wooded spot to take Hitler out. In the event they failed to kill him on the way to the teahouse, he would inevitably be driven back to his house, presenting another opportunity to take him out.

But the Berghof was deep in the heart of Nazi territory. Whoever was assigned the task had to be physically and mentally fit, a great marksman, and fluent not just in German, but also in the accent of the region so as not to stand out. It was not intended to be a suicide mission.

They ended up choosing a German-speaking Pole and a British sniper. The plan was to dress them up in German Army uniforms, then parachute them into the vicinity where they’d hide out till the time was right.

To accomplish that, they needed one other thing – an inside man. Fortunately, they had a German POW identified only as Diesler. He had an uncle named Heidentaler who lived in Salzburg, a mere 20 kilometers from the Berghof. Even better, Heidentaler was virulently anti-Nazi.

The man was a shopkeeper who did shooting practice at a target range some 16 kilometers from Hitler’s mountain retreat, so he knew the area. And best of all, he also wanted the German chancellor gone. He would have been more than happy to host the two men till that was accomplished.

The sniper got to practice with an accurized Kar 98K, the standard rifle used by the German armed forces. He was also given a 9mm Parabellum Luger pistol with a suppressor to quietly take out any problems on the way to the estate. Training was done in conditions similar to the one that he and his partner would encounter in Bavaria.

Everything was in place, and the plan was submitted in November 1944, but not everyone was happy with it. Lt. Col. Ronald Thornley, deputy head of the SOE’s German Directorate, argued that killing Hitler was a bad idea.

Hitler’s death might give Germans an excuse to blame their failure on his demise, not on their flawed ideology. His murder may also give rise to a myth that Germany might have won if the Führer had lived. It would have been a repeat of post-WWI when Germany blamed its loss on everything but their flawed plan to take France, a mentality that led to WWII. To avoid WWIII, therefore, Hitler had to fall in battle, not from an assassin’s bullet.

More importantly, Hitler was an awful strategist. He demanded absolute and centralized control of his armed forces, believing he knew better than his generals on the field. He, therefore, hurt, not helped, Germany’s war effort. If he was gone, he might be replaced by someone who was an effective strategist.

And so Hitler was allowed to live because he was the best inside man the Allies had in Nazi Germany.