In July 1944, Allied armies were fighting the Nazi German occupiers in Normandy, northern France. They had successfully gained a foothold and were pushing inland but were contained against the coast.

At the eastern end of the combat zone, the British army, with the Canadians, Poles, and other troops fighting under its command, had been stuck on a single objective since the start. The Germans tenaciously clung to the strategically important port city of Caen.

The Plan

On the 10th of July, General Miles Dempsey brought a plan to General Bernard Montgomery, the British Commander-in-Chief. It involved using mass armor to break out around Caen. Over the following days, they refined the plan and prepared it for launch.

Operation Goodwood would have two main thrusts. Bombers would blow open a corridor through the German lines outside Caen, letting three British armored divisions under General Richard O’Connor make a swift strike towards Falaise.

Meanwhile, Canadian forces would push out of the limited parts of Caen they held and capture the rest of the city.

Once they broke through, the British and Canadians could make the most of their numerical advantage, outnumbering the Germans two to one in terms of infantry and four to one in tanks. Goodwood would open up the opportunity for wider successes.

A Rough Start

The planning for Goodwood assumed that the attack would be a surprise to the Germans, but this proved impossible to achieve. Assembling the forces involved drew attention. 36 hours before Goodwood was due to begin, British intelligence intercepted a German message that showed they had anticipated the offensive and were preparing for the attack.

Montgomery lost some of his confidence and the objectives became more limited, with references to Falaise removed.

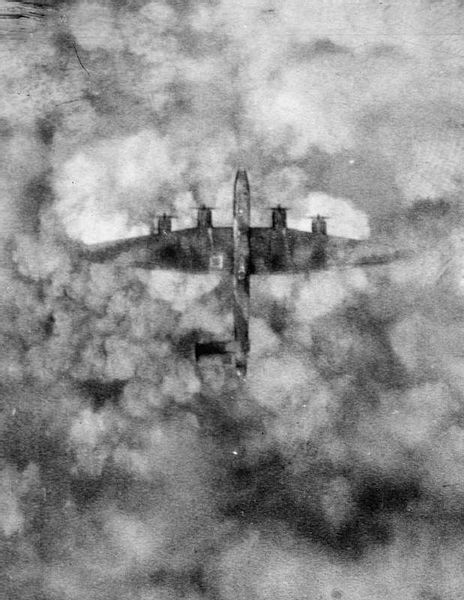

At 5:30 am on the 18th of July, the bombing began. For three hours, one of the largest ever air-to-ground attacks fell upon Panzer Group West. Men, tanks, and guns were scattered broken across the countryside.

In the wake of the bombardment, Allied forces surged forward.

They now learned again a lesson endlessly repeated during the First World War – the surprising ability of soldiers to survive a heavy bombardment and fight back in its wake. The remaining Germans regrouped and prepared to hold the Allies off. Anti-aircraft guns were turned against tanks while infantry defended the ruins and craters left to them.

Further problems complicated the attack. Minefields laid to protect British positions now stood in the way of their advance, channeling the tanks into narrow corridors. Traffic jams ensued. The loss of 11th Armored’s only forward air controller hampered their ability to call in air support.

A Failing Dream

The swift, decisive thrust Montgomery had dreamed of became bogged down amid mounting casualties. By the end of the first day, the Canadians had taken most of Caen, but the British fell short of their objectives. Critically, the Germans still held the Bourgébus Ridge, high ground which stood in the way of the Allied advance.

Montgomery was either unaware of these difficulties or in denial about them. He gave a briefing to reporters that talked of a great breakthrough, leading to wildly optimistic stories in the newspapers the next day. In trying to bolster his position politically, Montgomery actually undermined it by making promises that would not be kept.

Meanwhile, the troops at the front became increasingly weary and bitter.

O’Connor had understood one of the most important lessons of the war – that infantry and tanks worked best in coordination, supporting each other in an advance. Yet he only half acted on this, leaving his tanks and infantry with different objectives which stood in the way of full cooperation.

Matters were made worse by the terrain. The Normandy countryside, which so far had been densely packed, became more open around Caen. This gave the Germans a better field of fire with which to gun down the advancing British.

The British tanks weren’t as tough as their German counterparts and suffered from fighting in the open. They started to miss the cover that had previously benefited their opponents.

For once, the intelligence advantage was also on the German side. They had done a good job of surveying the British and Canadian forces, and so knew what to expect.

Persisting

Though the breakthrough didn’t happen on the first day, Montgomery persisted. This was an important operation for him and for the Allied armies.

For three more days, the British and Canadians fought on around Caen, trying to make a great breakthrough. The Germans dug in, reinforcing their positions on the Bourgébus ridge and fighting back tenaciously.

By the end of the fighting, 5,537 men were lost on the Allied side, along with 400 tanks, a third of the British armor in France.

At last, a thunderstorm forced an end to proceedings. Operation Goodwood drew to a close.

The Impact of Goodwood

Goodwood is often credited with drawing German forces away from American positions further west. There, Bradley was launching Operation Cobra, the attack that broke through the enemy lines and ended the containment against the Norman coast. Cobra led directly to the surrender of German forces outside Falaise and the Axis withdrawal east and out of France.

But Goodwood also lost the Allies one of their advantages. Until then, Hitler had remained convinced that another invasion force would be landing around Calais. The ferocity of the Goodwood attack told him otherwise. He redirected the 250,000 men of his Fifteenth Army towards Normandy. Fortunately for the Allies, they arrived too late to prevent the breakout.

In the aftermath, Montgomery tried to redefine Goodwood’s aims. He said that it had always been about distracting the Germans from Cobra and so was a success. But the heavy casualties and failed objectives told a different tale. Goodwood would remain a subject of controversy for years to come.