Everyone knows about the first bombing of Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941. Less well known, however, was the second attack. And there was almost a third…

The first one was just a warm-up. The Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) planned several more attacks on the US mainland – starting with California and Texas. It was called Kē-Sakusen (Operation Strategy) better known as “Operation K.”

Its aim was four-fold: (1) to assess the damage at Pearl Harbor; (2) to stop the ongoing rescue and salvage operations; (3) to finish off targets unscathed by the first raid; and (4) to test their new Kawanishi H8K1 flying boats.

Code-named “Emily” by the Allies, these planes were built for long range reconnaissance missions and could land on water. Heavily armed with ten machine guns and 20mm cannons, they could also carry eight 550-pound bombs; so you can see how they earned their other name, too – “Flying Porcupine.” They literally bristled with weaponry.

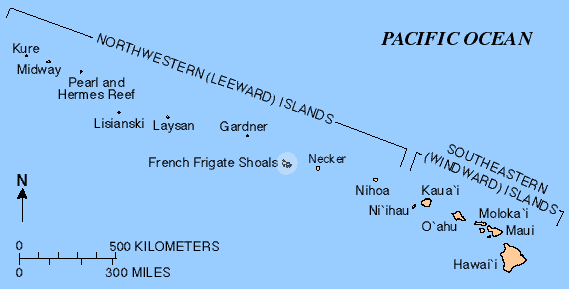

Able to travel for up to 24 hours without refueling, they were ideal for Operation K – or so the IJN hoped. Five were to fly to the French Frigate Shoals (Kānemilohaʻi) – less than 500 miles from Pearl Harbor. There they’d be refueled by submarine I-23 for the next leg of their flight to Oahu.

To light their way, they were to reach Pearl Harbor on the night of a full moon – March 4, 1942. Their primary target was the “10-10 Dock” (so named because it measured 1,010 feet long).

The mission was so important that the IJN dispatched another three subs to the area. As secrecy was essential, they kept radio communications to an absolute minimum. In fact, they were too successful at this; no one realized that I-23 and its entire crew had vanished – most likely after February 14, 1942. Its fate remains a mystery to this day.

As well as refueling the flying boats, I-23 was supposed to assess the weather over Oahu based on decrypted US Navy codes. But the IJN hadn’t heard from the submarine, so they assumed that the skies over Pearl Harbor were just dandy – so Operation K was on!

Except that the Kawanishis started acting up, which left them with only two. In command was Pilot Lieutenant Hisao Hashizume aboard the Y-71, with Ensign Shosuke Sasao flying the Y-72 – both members of the elite 801 Kokutai Fighter Squadron.

On March 3, they flew to the Wotje Atoll in the Marshall Islands where they were each given four 550-pound bombs and refueled for the next leg of their trip. Neither were given an escort because Japan had no other planes capable of such a long range flight.

Fortunately, American codebreakers figured out what was happening – just as they had with the first bombing. Unfortunately, they were again ignored.

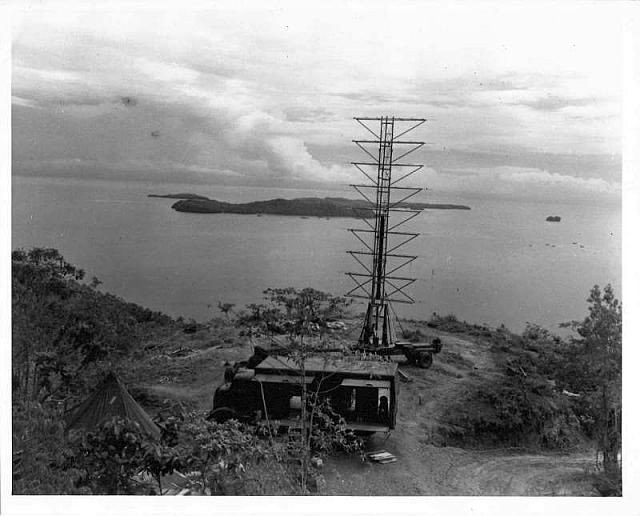

Thankfully, they couldn’t ignore radar. The Women’s Air Raid Defense (WARD) picked up the Kawanishis coming in from the northwest of Oahu, so fighter planes flew out to welcome them.

Sadly, radar technology wasn’t so good, back then. The US military believed that a mass fleet was headed their way – a repeat of the first attack. Worse, the weather was lousy and there was very thick cloud cover.

This meant they couldn’t find the Japanese. This wasn’t entirely a bad thing, because it also meant that neither Hashizume nor Sasao could see where they were going.

They did make it to the coast of Oahu at around 2 AM – avoiding the Americans, though not by design. Visibility was so poor that Hashizume became desperate and radioed Sasao, telling him to fly north so they could bomb Pearl Harbor together.

But Sasao didn’t get the message. He instead turned south. So now the Kawanishis were approaching Pearl Harbor from two different directions, while the Americans continued their desperate search.

Following the first bombing, all of Hawaii was under a blackout – making it even more difficult for Hazishume to find his target. Getting frustrated, he dropped his bombs from 15,000 feet… six miles shy of his target.

They fell on the side of the Tantalus Peak (an extinct volcano) near the Roosevelt High School – shattering windows and leaving four craters some 30 feet wide and 10 feet deep. Mercifully, no one was there.

Sasao didn’t fare too well, either. His only point of reference was the Ka’ena Point lighthouse, which he had used to bank south. Using guesswork, he dropped his bombs closer to Pearl Harbor… but into the sea. Again, no one was hurt or killed.

As previously arranged, Sasao then flew back to the Wotje Atoll, but Hashizume couldn’t. His Y-71 had problems even before take-off, and it was starting to show. So Hashizume instead flew to the Jaluit Atoll (also in the Marshall Islands) for repairs.

Reporters in Los Angeles went berserk. A radio broadcast claimed that the second attack on Pearl Harbor killed 30 people and wounded another 70 – which never happened. The IJN intercepted the report, however, congratulated themselves, and deemed Operation K a success.

So they planned a third attack for May 30th. This would spearhead their invasion of the Midway Islands – part of Hawaii, but roughly between the US and Asia (hence the name). Submarines I-121, I-122, and I-23 were sent there on May 26th to await further instructions… from the Americans.

The US had already figured out that the Japanese were using Midway as their launching pad to Hawaii. On May 29th, Toshitake Ueno, commander of the fleet, raised his periscope… only to find two US destroyers on the surface.

If he sunk them, it would confirm that the Japanese were indeed using Midway, so he ordered a retreat. The problem was, no one else knew because Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto had imposed a complete communications blackout.

Which was why Admiral Chuichi Nagumo, head of the First Carrier Striking Force, made his way toward Midway. He thought that the Americans were still in Pearl Harbor.

This time, however, America listened to its codebreakers. Nagumo sailed into a trap, losing four of his large aircraft carriers, while the US lost only one destroyer and one aircraft carrier.

The Battle of Midway (June 4-7, 1942) cost Japan dearly – not just losing irreplaceable carriers, but also because they could no longer use Midway or Hawaii as a springboard to the US mainland.