Reuters described Operation Longcloth as “the greatest guerrilla operation ever undertaken.” Louis Allen wrote that it “had panache, it had glamor, it had cheek.”

It may have seemed less glamorous to the soldiers taking part. They slogged through the jungles of Burma in WWII, short on supplies and hunted by the Japanese. In doing so, they proved the value of long range expeditions behind enemy lines. Success, however, came at a heavy cost.

The Battle for Burma

The Battle for Burma was a constant of WWII in East Asia. Shortly after Japan went to war against the Allies, Japanese troops poured through the British territory. The British were pushed back swiftly, almost to the border of their vital colony of India.

By the beginning of 1943, the British and Americans were preparing to push back.

Long Range Penetration

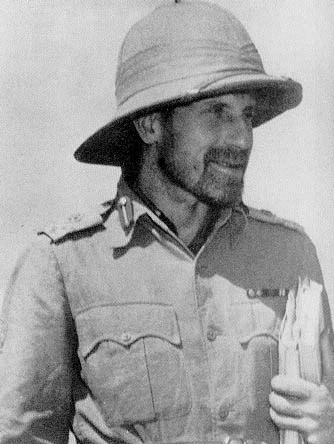

The most controversial figure in the fight back was a British officer named Orde Wingate. He had a strong personality and a tendency to aggravate traditional officers. A bold thinker and a specialist in irregular warfare, he had developed a strategy called Long Range Penetration (LRP).

LRP involved brigade strength forces infiltrating Japanese territory. Supplied by air, they caused havoc against enemy supply and communication lines.

To achieve it, the British Army created a special force called the Chindits. Tough training and a focus on independent action prepared them to serve deep in the Burmese jungle.

Difficult Journey Across the Lines

Operation Longcloth was the first time the Chindits and LRP were tested. It was originally meant to be part of a wider advance by British and American forces. When the advance was canceled, Wingate decided to go ahead with his part. If he did not act, then his opponents within the British Army might stop him having another chance.

On February 12, 1943, the Chindits set out. 2,000 men marched east while others headed south as decoys. They were divided into small, independent columns. It was an arduous journey through the jungle and across rivers that were a mile wide in places. Some columns lost contact with their comrades and were lost.

Despite this, by March 1, four columns had reached a safe area deep behind Japanese lines.

First Attack

The Chindits were close to the routes used to supply Japanese troops facing the Americans in the north. They set about disrupting those lines.

Michael Calvert, one of the best Chindit leaders, led an assault on Nankan station. His forces inflicted heavy casualties on the Japanese with no losses themselves. They destroyed the station, track, road, and bridges. They left mines and booby-traps to hinder Japanese rebuilding.

Meanwhile, Bernard Ferguson’s column destroyed the railway at Bonchaung gorge. A fight with a Japanese patrol cost them casualties and injured men had to be left behind.

Across the Irrawaddy

The columns continued their journey across the Irrawaddy River. Intelligence had advised there was a safe area to work in on the far side.

The information was wrong. After struggling across the river, the Chindits found dry, inhospitable territory. In the absence of other Allied advances, the Japanese focussed on hunting the Chindits, using the areas many roads to their advantage. It made air drops difficult, leaving many men short on rations. Exhaustion began to kick in.

Called Back

Wingate considered what to do. North would take them toward more favorable terrain, Japanese lines, and eventually the Americans. East lay the Burma Road and a journey to China.

Then orders arrived for him to abandon the expedition and bring his troops home.

It was a difficult choice for Wingate and the officers on the ground. They understood how difficult the withdrawal would be, given the terrain and the attention of the Japanese. After much debate, Wingate decided to follow the order.

The Chindits were told to leave their heavy equipment behind and head back across the Irrawaddy. On the far side, they split up into small groups, hoping to get as many men home as safely as possible.

Another Difficult Journey

The return trip was different for each group. Some men never made it back. Those who did suffered from hardship and deprivation along the way.

Some reached friendly locals who supported them and helped them find safe ways.

Some were picked up by a brave pilot who landed on a hilltop while dropping off supplies.

Some made it to a Chinese base and were flown out by American supply planes.

Wingate’s group rested for a week, regained strength by eating their mules, and then marched home.

Costly Yet Effective

Of the 3,000 men who set out, 1,000 were lost. Much valuable equipment was left behind. On the face of it, the expedition had achieved little and cost a lot.

It did have an effect. It disrupted supply lines. Three whole divisions of Japanese troops were sent to hunt them down. The Japanese commander Mutaguchi had to change his entire approach for 1943.

Longcloth taught Wingate and the British, valuable lessons about how they could use LRP.

Responses to Operation Longcloth

Responses to Operation Longcloth had little to do with its military effectiveness.

Having arrived home on April 25, almost immediately Wingate was flown to a press conference in Delhi. There he talked up the successes and the inspiring story of the operation.

It was news the Allies badly needed, and the press were willing to hear. Compared with the defeats and withdrawals in the rest of Burma, it gave people something hopeful. It was this attitude that led to the glowing appraisal by Reuters.

The British officers in Delhi, most of whom had never faced the Japanese, were deeply cynical. Most of them detested Wingate and poured scorn on his achievements.

Longcloth had been a tough expedition but a useful one. For all the hype and all the cynicism, on its own terms, it was a costly success but proved the value of LRP.

Source:

David Rooney (1999), Military Mavericks: Extraordinary Men of Battle.