It’s hard to imagine a worse attack on Japan during World War II than the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, but there was. The firebombing of Tokyo in March 1945, the largest air raid of the conflict, saw the deaths of 100,000 individuals, along with the displacement of more than one million residents and the destruction of hundreds of thousands of structures.

Why did the American forces launch the devastating attack on areas heavily occupied by civilians, and should the air raid have been deemed a war crime?

Fight in the Pacific Theater was brutal

Japan had long planned an aggressive expansion campaign in the Pacific Theater and knew it needed to prevent the United States from getting involved. As such, the decision was made to obliterate the country’s naval forces, in what became the attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941. The belief was that, by the time the US Navy had rebuilt, the Japanese forces would have taken both the Philippines and British Malaya.

The surprise assault led to America’s entry into World War II. Undeterred, the Japanese continued to expand, capturing a host of territories throughout Southeast Asia and the Pacific. The American forces responded with counterattacks and offensives, such as the Battle of Midway in June 1942, which significantly weakened the Imperial Japanese Navy’s (IJN) fleet.

By 1944, the Allies had gained significant momentum in the Pacific Theater, capturing strategic islands like Saipan, Tinian and Guam, which brought Japan within the range of American bombers.

This relentless push aimed to cripple the enemy’s ability to wage war. Despite continually facing fierce resistance, the American forces continued their island-hopping campaign, gradually closing in on the Japanese mainland. The capture of the Mariana Islands was particularly crucial, allowing for the deployment of the Boeing B-29 Superfortresses capable of reaching the country. This set the stage for a new phase of strategic bombing, aimed at breaking Japan’s industrial and civilian morale.

Doolittle Raid

The Doolittle Raid, conducted on April 18, 1942, was the first air raid by the United States against the Japanese home islands. Led by Lt. Col. James Doolittle, 16 North American B-25B Mitchells launched from the USS Hornet (CV-8), targeting Tokyo and other major Japanese cities. After they’d hit their targets, they were to fly to China, where they could safely land.

While the assault inflicted minimal physical damage (just five patrol boats were lost, while a larger vessel suffered damage), its psychological impact on the country was profound. It demonstrated that Japan was vulnerable to American air attacks and boosted Allied morale. It also forced Japan to divert resources to its homeland defense, altering the military’s strategic priorities.

Despite the loss of all aircraft involved (15 were completely destroyed, while one was captured by the Soviets), with some aircrews captured and executed, the Doolittle Raid was a significant propaganda victory for the Americans forces. It marked the beginning of a sustained aerial campaign against Japan, culminating in the devastating firebombing of Tokyo in 1945.

Planning the firebombing of Tokyo

The planning of the firebombing of Tokyo, codenamed Operation Meetinghouse, involved meticulous preparation and strategic shifts. Maj. Gen. Curtis LeMay, who took command of the XXI Bomber Command in January 1945, played an important role, recognizing that high-altitude precision bombing was ineffective, due to Japan’s unpredictable weather and jet streams. As such, he proposed a radical change: low-altitude (5,000 feet), nighttime incendiary raids.

LeMay’s plan faced initial resistance, due to concerns about aircrew safety and the ethical implications of targeting civilian areas. However, the need to expedite Japan’s surrender and avoid a costly invasion outweighed these concerns, as did the knowledge that both the country’s night fighter force and nighttime anti-aircraft defenses weren’t as effective as the Japanese believed them to be.

The operation aimed to destroy Tokyo’s industrial capacity, which was interwoven with residential areas. The US Army Air Forces (USAAF) B-29 Superfortresses were stripped of their defensive armament to increase bomb load and fuel efficiency, underscoring the high-risk nature of the mission.

March 9-10, 1945: Firebombing of Tokyo

On the night of March 9-10, 1945, 334 B-29 Superfortresses took off from bases in the Marianas, for Tokyo.

Operation Meetinghouse began with pathfinder aircraft dropping incendiaries to create a fiery “X” that marked the target area. Following this, the main bomber force unleashed 1,665 tons of incendiary bombs – primarily M-69 napalm bomblets – over the densely populated districts of Kōtō and Chūō. Of the total number of B-29s that participated in the attack, 282 made it to their targets.

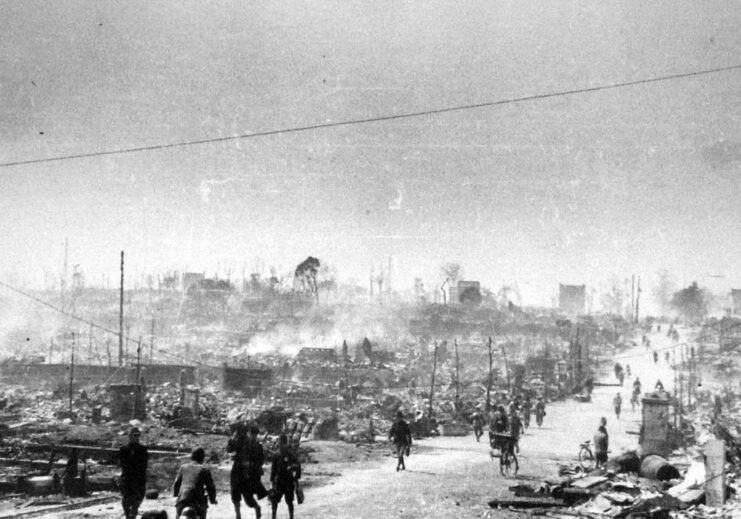

The bombs ignited a massive firestorm, with the flames fanned by strong winds of up to 28 MPH. The intense heat, reaching up to 1,800 degrees Fahrenheit, created a conflagration that consumed 15.8 square miles of the city. The firebombing of Tokyo lasted for several hours, with the American bombers flying at altitudes between 5,000 and 9,000 feet to avoid anti-aircraft fire.

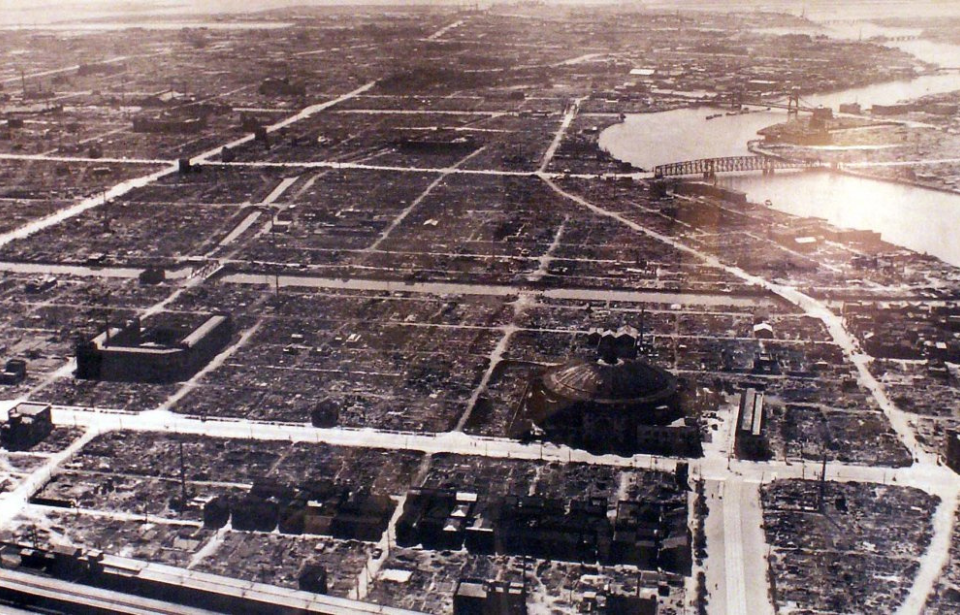

The destruction was unprecedented, and it wound up becoming the deadliest air raid of World War II, surpassing that of Dresden and the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

Aftermath of the firebombing of Tokyo

The aftermath of the firebombing of Tokyo was catastrophic. An estimated 100,000 people were killed and over one million were left homeless. The firestorm obliterated 267,171 buildings, decimating Tokyo’s industrial and residential areas.

The psychological impact on the Japanese populace was profound, as the air raid further shattered the illusion of invulnerability and exposed the dire state of Japan’s defenses.

International reactions were mixed, with some viewing the attack as a necessary step to hasten the end of World War II, while others condemned it as a war crime, due to the high civilian casualties. The destruction of Tokyo’s industrial base significantly impaired Japan’s war production capabilities, contributing to the eventual Allied victory.

Efforts to rebuild

Rebuilding Tokyo after the firebombing was a monumental task. In the immediate postwar years, the city struggled with limited resources and a devastated infrastructure. The subsequent US occupation prioritized economic stabilization over extensive reconstruction, and it wasn’t until the 1950s that Tokyo began to witness significant economic growth, driven by industrialization and international aid.

More from us: The March on Rome and Benito Mussolini’s Quest to Turn Italy Into a Fascist Nation

Memorials dedicated to the victims of the firebombing of Tokyo have been established, such as the cenotaph in Yokoamichō Park, which houses the ashes of 105,400 individuals. The Center of the Tokyo Raids and War Damage, founded by survivor Katsumoto Saotome, serves as a repository of documents and personal accounts, ensuring that the memory of the tragedy endures.