Great Britain’s success in holding out against Nazi Germany has become the stuff of national legend. The only country in Western Europe to successfully stand against the Nazis throughout World War Two, it was kept safe by the English Channel, thanks to which only the Channel Islands were invaded by Hitler’s troops.

But Hitler did have a plan to invade Britain, and he came close to executing it.

Reaching for Peace

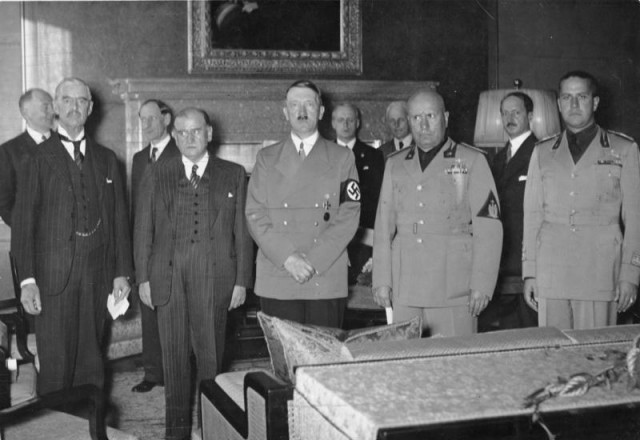

The attitude of Nazi Germany towards the United Kingdom was a complicated one. On the one hand, the Nazis admired the British, with their strong military tradition, their overseas empire and their northern European heritage. They saw them as kindred spirits.

On the other hand, Britain was one of the countries that had humiliated Germany in the Treaty of Versailles at the end of the First World War, and on whom Hitler intended revenge. Britain remained allied with France, one of Germany’s staunchest enemies, and had been making diplomatic maneuvers aimed at containing Germany.

Even though the British contributed troops to the failed defense of France in 1940, Hitler still hoped that Britain and Germany might make peace. Following France’s fall, he avoided preparing an invasion of Britain for a month, while he waited to see if the British would give in. But it soon became clear that they would not.

Directive No. 16

On 16th July 1940, Hitler signed Führer Directive No. 16. This gave the go-ahead for the invasion of England, a plan titled Operation Sealion. After making one last bid for peace on 19th July, he pushed ahead with the plan.

The month’s delay worked in Britain’s favor. The British had been preparing their defenses and stockpiling ammunition. On top of this, the timing would be crucial for a crossing on the English Channel. If, as the British believed, the Germans could not be ready before mid-September, then weather might hamper the invasion.

But the Germans were more ready than the British thought, and the invasion was planned for the 25th of August. Forty-one divisions would cross the Channel, along with two divisions of airborne troops. Landing along the south coast, they would encircle London, bringing the British government to its knees. It was a detailed and well-considered plan.

Preparing the Fleet

As the invasion fleet was assembled, the Germans began to hit snags. Grand-Admiral Raeder pointed out that not all of the planned thirteen divisions could possibly be landed in the first wave – the boats simply didn’t exist for this, and even if they did he could not defend such a fleet against the Royal Navy. So the force was reduced to twenty-seven divisions, and the occupation of Devon dropped from the plan.

Ingenious solutions were found to the problems of invading the British coast. Tanks were waterproofed and fitted with snorkels so that they could be dropped off in thirty feet of water and drive up onto the beaches. The French coast between Boulogne and Sangatte was filled with artillery batteries capable of firing all the way across the Channel, to give the fire support the Navy was unable to provide.

Like the Allies’ later D-Day plans, Operation Sealion was marked by daring and ingenuity.

Directive No. 17

Even with the French coastal artillery, the German army and navy would not be able to pound the British heavily enough to support the invasion. For that, they needed air support – massive attacks against Britain’s coastal defenses by bombers such as the Stuka dive-bomber. Without that sort of firepower to soften up the British, German troops would land against terrible odds.

This meant that the Germans needed air superiority. Without it, British fighter pilots and their allies who had fled occupied countries such as France and Poland would be able to attack the incoming bombers. Fighting over their own territory, the British would be able to turn their craft around faster and keep the German planes under constant attack, preventing tactical bombing runs.

And so Hitler signed Führer Directive No. 17 on the 1st of August, ordering the Luftwaffe, the German air force, to dedicate itself to the swift destruction of the Royal Air Force.

The Battle of Britain

Upping the ante of their ongoing bombing campaign, from the 8th August the Luftwaffe sent up 1,500 aircraft over Britain each day to bomb radar stations and airfields. The Battle of Britain had begun.

The British had the technological advantage in their advanced radar stations and the home ground advantage of being able to retrieve their downed pilots. But the sheer ferocity of the German attacks started to take its toll. By early September, critical airfields were covered in bomb craters that hindered their use. Aircraft had been destroyed on the ground as well as in the air, and the supplies of both planes and pilots were starting to run out.

The nature of the battle shifted following the night of the 24th of August when a German plane accidentally bombed a civilian part of London. Churchill ordered retaliatory strikes against Berlin, which distracted Hitler from his focus on the RAF. Both sides descended into bombarding each other’s cities rather than air bases. The RAF had been saved.

An Autumn Invasion

Plans for Operation Sealion continued, delayed by the needs of the air war. A revised launch date of the 24th September was set. The German navy swept for British mines and laid others of their own to secure invasion lanes across the English Channel.

But the attacks these mine ships suffered were a symptom of a wider problem. Without aerial superiority, the invasion was too risky. On the 14th of September, Hitler pushed the invasion date back to the 27th, the last day of suitable tides. On the 17th, Sealion was postponed indefinitely, and on the 19th of September, the fleet was dispersed so as to avoid being a target for enemy bombers.

By the time weather improved in the spring, Hitler’s attention had turned east to fighting Russia. Operation Sealion would never be launched. Britain had been saved.