They had difficulty rallying due to poor visibility, and came under heavy small-arms fire, artillery fire, and mortars.

The Second World War was going well for the Allies in March 1945. The last significant German offensive of the war had been destroyed during the Battle of the Bulge, and the Allies had pushed into Germany itself.

However, there were a few significant obstacles remaining to the Allied advance. One of these was the heavily fortified German line along the Rhine River, a natural barrier running across western Germany, and the Germans were prepared to hold it.

General Dwight Eisenhower and Field Marshal Sir Bernard Montgomery agreed to attempt river crossings at several locations. This plan was code-named Operation Plunder. However, Montgomery felt that Operation Plunder needed more support and devised what was to be known as Operation Varsity.

Goals and Strategy

Operation Varsity was based around a massive airborne assault. The audacious plan called for three airborne divisions to take part in the assault. Unfortunately, only one of these divisions, the British 6th Airborne, had any significant combat experience.

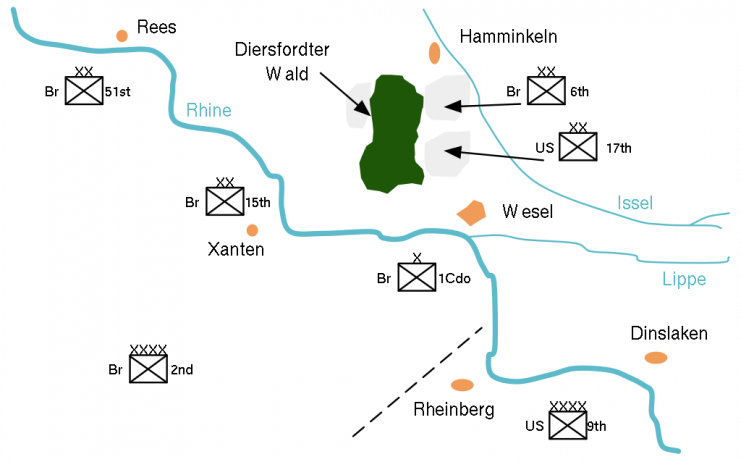

The Allies encountered another roadblock to their plan when they discovered they only had enough transport aircraft for two divisions. One of the green American divisions would therefore have to be left behind. Ultimately, this left only the British 6th and the American 17th to carry out the operation.

The paratroopers’ primary objective was to disrupt the Nazi defenses around the city of Wesel. Their operational orders were to disrupt German defenses along the Rhine River and take key positions to assist the British Second Army’s offensive operations.

After taking several key objectives behind German lines, the airborne forces would also have to hold off counter-attacks until the main Allied forces could cross the river.

There were a number of key differences between the Operation Varsity landings and those of other airborne operations such as Market Garden. First, the Allied ground forces would attack before the airborne divisions landed. Second, the airborne divisions would land much closer to German positions than in previous operations. Finally, they would all land simultaneously, rather than being spread out across multiple landings over a few hours.

These changes were primarily designed to minimize risk to the airborne forces by allowing them to quickly link up with the main ground force.

The Attack

As Field Marshal Montgomery launched his ground assault, 1,600 planes with 17,000 troops flew overhead. The force was so large that it took over two and a half hours for the entire formation to pass over a given area. The American forces were to land separately from the combined British and Canadian force, and were tasked with securing their own set of objectives.

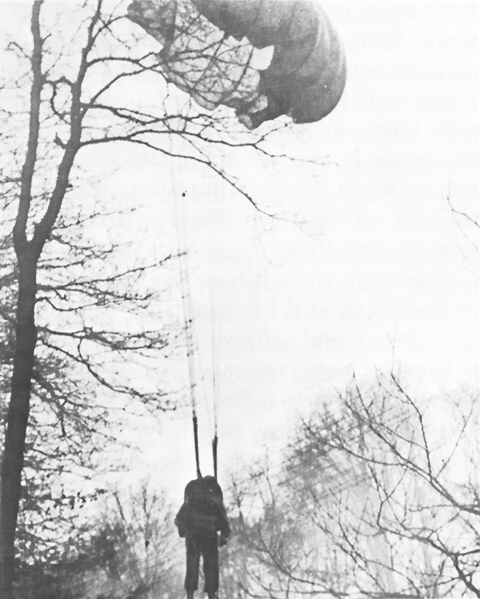

Although Operation Varsity was the largest single-day airborne drop in history, they faced significant opposition. The landings were difficult despite the fact that the German forces were not at full strength after years of fighting. The first forces touched down around 10.00 a.m. and immediately encountered small arms and anti-aircraft fire.

The American Assault

The drop zones were obscured by a morning haze which meant that some of the troops landed off-target. This included Colonel Edson Raff, the regimental commander. Raff and his men gathered together to push around two miles to their intended landing site, taking out machine gun and entrenched German positions along the way. Another group, under Major Paul Smith, destroyed a number of anti-aircraft positions.

The 507th’s 2nd and 3rd battalions fought to secure Diersfordter and a castle in the area. They took out two tanks, one of them by using a 57mm recoilless rifle. The castle was cleared one room at a time and secured it by around 3.00 p.m., during which 300 German men and officers were captured. By this time the Americans had taken most of their objectives, destroyed several German positions, and captured around 1,000 prisoners.

British and Canadian Forces Assault

The 6th Airborne landed on target and cleared their landing site by around 11.00 a.m. The Canadian 1st Parachute Battalion suffered casualties on landing, including their commanding officer, Lieutenant Colonel Jeff Nicklin. Despite these losses, the Canadians were able to link up with the British 9th Parachute Battalion to capture their objective at Schnappenberg. By 3:45 p.m. they had captured all of their objectives.

The 5th Parachute Brigade, under the command of Brigadier Nigel Poett, was engaged in some of the fiercest fighting of the day. They had difficulty rallying due to poor visibility, and came under heavy small-arms fire, artillery fire, and mortars. However, the 7th Parachute Brigade arrived and helped secure the drop zone. The 12th, and 13th Parachute Battalions then landed and took their objectives as well.

The British 5th and 7th Parachute Brigades then moved towards Schnappenberg to link up with the British 9th and Canadian 1st Parachute Battalions. They routed all the Germans in their path, and by 3.30 p.m. the British and Canadian Forces were united. Three intact bridges across the River Issel were among the most important objectives they captured. They also captured the village of Hamminkeln together with the American 513th Parachute Infantry Regiment which had mistakenly landed nearby.

Outcome

The Allied paratrooper forces held off several German counter-attacks until around midnight when they were reinforced by infantry that had crossed the Rhine during the main Allied assault. Allied forces continued crossing the river, while the Germans achieved no successes with their counter-attacks.

In regards to its stated objectives, the operation was a spectacular success. All the objectives were captured quickly and the individual units united after landing and fought cohesively. Additionally, the British paratrooper brigades successfully fought through German lines to unite. Although Allied casualties during the operation were lower than expected, they were still high. The Allies suffered around 2,500 casualties, while they captured 3,500-4,000 Germans and inflicted an unknown number of other casualties.

Many of the Allied casualties occurred during or shortly after the landings. The C-47s the Americans used performed poorly during the mission, largely owing to its vulnerable fuel tank which was easily punctured. German incendiary rounds could cause the planes to burst into flames. The planes were never used for such operations again.

Legacy

Military leaders at the time debated whether the assault was necessary and whether it was better than the alternative of simply focusing entirely on an attack across the Rhine. Historians disagree to this day. Some point out that the operation suffered from higher casualties than the attack across the Rhine, and that the main Allied attack did not struggle and so did not require the airborne support.

Meanwhile, other historians argue that one reason that the river crossing was not more staunchly opposed was because the Germans were thrown into disarray by the airborne troops. Captured German Generalmajor Fiebig supported this argument, remarking that the attack had a “shattering effect” on his men.

Regardless of the wisdom behind Operation Varsity, the men who took part performed heroically. Private George J. Peters posthumously received the Medal of Honor after he defeated a German machine gun position by himself, even after being wounded twice during his charge.

Private First Class Stuart Stryker also received the Medal of Honor posthumously for leading a charge against another entrenched machine gun position. Although he was killed in the assault, his company successfully overran the position.

In addition, Canadian medical orderly Corporal Frederick Topham received the Victoria Cross for continuing to treat wounded soldiers despite being wounded himself and under heavy fire.

Read another story from us: The Capture Of The Bridge Over The Rhine At Remagen, 7 March 1945

Operation Varsity broke the back of German resistance on the Western Front and proved to be the last major airborne assault necessary for Allied victory in Europe. By April 1945 the Nazi regime was broken, Hitler’s forces hopelessly damaged, and the Allies had closed in on all sides. On May 7th, 1945, the German government signed an unconditional surrender.