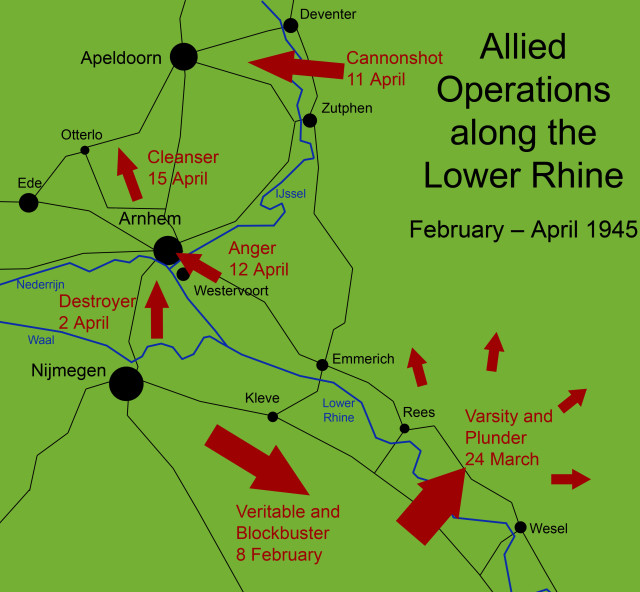

In early Spring of 1945, the Western Allies prepared to cross the Rhine, invading Germany and the areas still under the control of the Third Reich in Holland in 1945. The liberation of most of The Netherlands was tasked to the Canadian First Army.

After Operations Varsity and Plunder had pushed the Allies over the lower Rhine in late March, it was a mere month and a half before German forces in Holland offered their unconditional surrender on May 5th, just three days before the end of Word War II in the rest of Europe.

On April 11th and 12th, Canadian I and II Corps crossed the IJssel, a branch of the Rhine, from the East to attack German positions in the cities of Arnhem and Apeldoorn in Operations Anger and Cannonshot, respectively.

The assault on the German forces west of the IJssel was repeatedly delayed through the winter due to weather, allocation of resources, and the tactical benefits of waiting until the Rhine had been crossed first. Operation Anger was delayed until after artillery fire had enabled crossings on the IJssel to the north.

Whereas it was mostly Canadian troops crossing the IJssel to the north and capturing Apeldoorn, the force assaulting Arnhem was predominately made up of the British 49th Infantry Division, known as The Polar Bears, with some Canadian 5th Armored Division units attached and with the help of Royal Canadian Engineers.

Cannonshot

The beginning of Operation Cannonshot went off with barely a hitch as cover from artillery, bombers, and smoke screens shielded the Canadians crossing the IJssel and establishing a bridgehead at 3:30 PM on April 11th.

Since Allied commanders had long since learned the German tactics of reacting as soon as possible, the Canadians opted out taking advantage of the strategic surprise after crossing the river and pushing on towards the city of Apeldoorn and prepared for the expected German counterattack, which came at midnight and was repelled. The Germans suffered many casualties and by daybreak of the 12th, Canadian engineers had assembled a bridge for their tanks.

The rest of the operation, however, took longer than expected. The Germans held positions along the Apeldoorn Canal, which ran through the city, north-south. The German defenses were very strong both to the south and north, and the initial Canadian plan was to attack to the north. Dutch resistance relayed information that a bridge over the canal in Apeldoorn was intact, so a direct assault on the city was chosen.

Apeldoorn was still full of Dutch civilians, however, so aerial and artillery bombardment was not an option: this assault had to be done with tanks and infantry, street by street and house by house. Attacks into the city were repelled and the operation was dragging on for several days.

Luckily, by April 16th, the British and Canadian troops had captured Arnhem and were moving north. As the Germans pulled away from positions south of Apeldoorn, the Canadian II Corps were able to cross the canal unopposed. With the canal now lost, German troops abandoned the city as quickly as they could.

When Canadian troops entered Apeldoorn, they were astounded at the massive amount of riches plundered from the Dutch, the Germans had left behind or were attempting to carry when they were captured.

Altogether, Canadian deaths totaled over 100 with just over 500 casualties in total.

(Quick) Anger

Though far fewer Allied troops killed or injured in the assault on Arnhem, it was a much larger operation. When the Allies tried to take Arnhem the previous year, the results were disastrous. The British 1st Airborne Division dropped close to the city as part of Operation Market Garden were almost completely destroyed when the ground forces failed to reach them.

Dutch railway workers, in support of Allied operations, had begun a strike and, in retaliation, Germany banned rail freight that brought food inland and thousands of Dutch were starving though the winter.

Arnhem, itself, had been emptied of citizens and completely looted, so this time, the British and Canadians had no problems bombing it to kingdom come. For a whole day, artillery and aircraft rained death on the city. Hawker Typhoon fighter-bombers launched early British rockets to blow up buildings and tanks.

At 10:40 PM of April 12th, again under artificial smoke cover, but this time using amphibious tracked Buffaloes to cross the IJssel, the British and Canadians surprised the Germans who must have figured the main assault was coming from the south, across the Nederrijn river.

They experienced some casualties, but considering the Germans held the town with an estimated 1,000 men against an entire division of many thousands more, the Allies crossing the IJssel were meeting their objectives fairly quickly and soon had a Bailey bridge and pontoon ferries in place.

The remaining German and Dutch SS forces managed to hold a few strong points with machine guns and occasionally tanks, sometimes even for a full day. But they faced overwhelming numbers and equipment like the Churchill Crocodile, a flame-throwing tank.

By evening on the following day, the British and Canadian troops of the Canadian I Corps had all but cleared the city. Pockets of resistance and German positions outside the city were cleared over the next few days, with the rest of Holland liberated two weeks later.

Troops entering Arnhem found it not just bombed out, but nearly empty, aside from houses. The German’s looting the year before had left practically nothing of use in the city.

At Arnhem, at least 600 German soldiers were captured. In the city and the areas around it (which were occupied by a few thousands more German troops), between 1,600 and 3,000 casualties were reported, differing by source. The British and Canadians, in sharp contrast, suffered less than 200 casualties.

By Colin Fraser for War History Online