On December 9, 2014, a German court in Cologne dropped the multiple charges of murder and accessory to murder against an 88-year-old man named Werner Cristukat due to lack of witness statements and reliable documentary evidence. Not a huge surprise due to the fact that the crimes in question were committed on June 10, 1944, when the accused was 19 and a member of the 3rd company, 1st battalion, 4th SS Panzergrenadier Regiment, also called Der Führer.

Cristukat’s regiment, under the command of SS Major Adolf Diekmann, slaughtered almost every living soul they found in the French village of Oradour-sur-Glane that day: 190 men, 247 women, and 205 children were dead in a matter of hours.

Until the Allied invasion on D-Day, events like this in German-Occupied France were not prevalent. But now, they were on the rise as Germany became desperate to quell the reinvigorated French Resistance (Résistance or Maquis).

Of course, by this time, the SS already had made its reputation as a brutal and merciless force. The commander of the Waffen-SS Panzer Division, Das Reich (of which the 4th SS Panzergrenadier Regiment was a subordinate), SS-Major General Heinz-Bernhard Lammerding was previously head of anti-partisan operations behind German lines in Soviet Russia.

There, he had ordered many “retaliatory” actions (sometimes against people with absolutely no connection to partisans) which lead to the murder of thousands upon thousands of citizens. The Das Reich division, itself, was stationed in Soviet Russia for two years, before its transfer to occupied France, doing such work.

In early June of 1944, just after D-Day, the orders were handed down to German Army and SS officers to crush the French resistance without mercy. The tactics employed by officers like Lammerding in Eastern Europe, in places like Russia, Serbia, and Greece, of the utmost brutality, were now to be used in France.

On June 9th, Lammerding ordered his troops to “cleanse” the area of Clermont-Ferrand. In response to a partisan attack there, 2nd SS Division hanged 99 men from the village of Tulle.

The next day, Diekmann received information that a fellow officer of his 2nd SS Division had been captured by partisans around the village of Oradour-sur-Vayres. This action and the one for which 99 men were hanged the day before was apparently more than enough of an excuse to take their ruthless and unsavory actions to the next level.

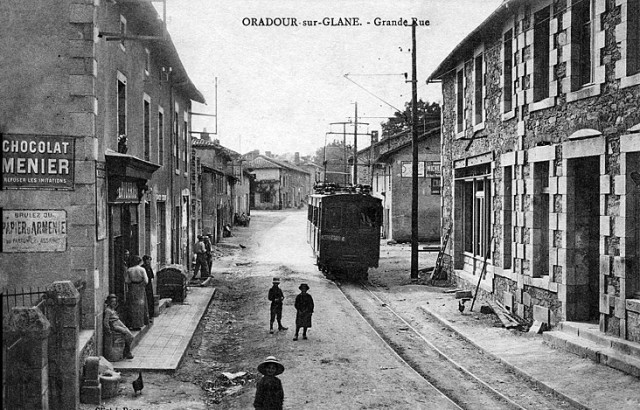

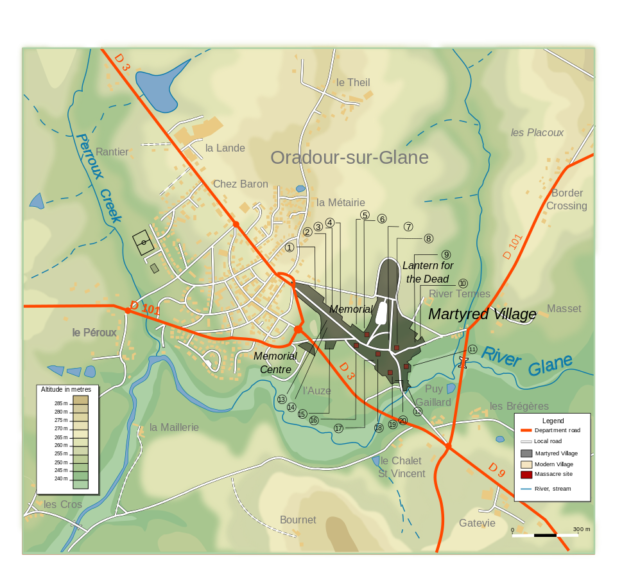

Diekmann and his 4th SS Regiment marched to the village of Oradour-sur-Glane (a little over 30km from Oradour-sur-Vayres and some 120km from the village of Tulle), surrounded it, and ordered every resident and a few passers-by to gather in the village square to have their identity papers checked.

School children, all in class, heard a few bursts of rifle fire before SS soldiers came in and rounded them and their teachers up to be taken to the square.

The villagers were then separated. The women and children were shuttled into the church, and the men were taken to several barns on the edge of town. With the eyes of history, most people know this is when things get bad. For the residents of Oradour-sur-Glane, this might very well have been the first time they did.

In the small, rural communities of Southern France, the effects of the occupation were far less than in the big cities like Paris: Few soldiers had been harassing them, the food was plenty, life was much as it was before the war. One addition, however, was the dozens of people who came to the village as refugees.

Several would have been Jewish, seeking to hide from the Holocaust. Many had been evacuated by the French government from Alsace. Because many of the Alsatians spoke German, they were distrusted and mocked by some locals who would often call them les ya-ya (referencing the German for “yes”).

Now, locals and refugees alike stood in large groups and had precious few moments left before the cruelty of the SS was unleashed upon them.

According to some of the few survivors, the SS soldiers sprayed the legs of the men with bullets after they were gathered into the barns. Then, as the Frenchmen lay there unable to move, the Germans either finished them with rifles or doused them with fuel and set them on fire. Six were able to escape this tragedy, one of whom was shot later as he limped down the road.

Over in the church, two SS soldiers carried a large box through the sanctuary and placed it on the alter, leading fuses away from it. When it was lit, black smoke roared out, choking the women and children in the church. Then, the front doors were reopened and machine-gun fire pelted those who stood among the pews. The SS soldiers quickly placed down burnable material around the bodies and lit a fire. Only one person survived the bloodshed in this church.

Marguerite Rouffanche, aged 47, spotted the stool behind the altar where she crouched in fear, trying to find breathable air. She used it to help heave herself out the window. She dropped about three meters, followed by another woman and her infant child. As they all landed outside of the window, they were shot where they stood. Though her neighbors lay dead, Rouffanche was only wounded and managed to find cover in nearby rows of peas, where she hid until morning.

Before leaving, the Germans looted and torched the village.

One report of the aftermath (of what some believe must have been Oradour-sur-Glane) comes from Raymond J. Murphy, an American navigator whose B-17 was shot down in the French countryside. After help from the French Resistance, he was flown to England and wrote this report of a village he came to as he was avoiding German soldiers behind enemy lines:

“About 3 weeks ago, I saw a town within 4 hours bicycle ride up [sic] the Gerbeau farm [of Resistance leader Camille Gerbeau] where some 500 men, women, and children had been murdered by the Germans. I saw one baby who had been crucified” (source: wikipedia.com).

Outrage at this incident was, quite understandably, immense. The Germans, in an effort to appease some of the horror and anger of the Vichy Government, began an inquiry into the actions of the SS regiment, which didn’t go far and was soon dropped.

After the war, French President Charles de Gaulle ordered that the village not be restored, but instead remain a memorial to those who were murdered.

In 1999, a museum, containing personal effects and items found in the burned down structures, was also dedicated to the Village Martyr, the Martyred Village, Oradour-sur-Glane

By Colin Fraser for War History Online