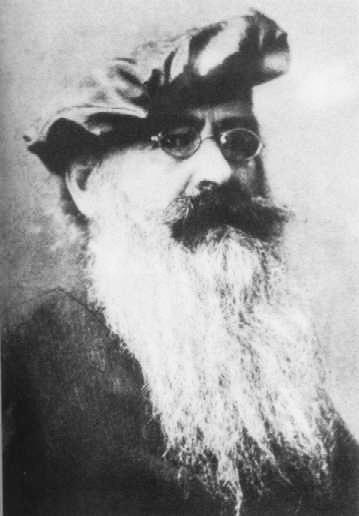

Otto Wilhelm Rahn was a German writer and medievalist who was obsessed with finding the Holy Grail. This was the cup that Jesus supposedly drank out of during the Last Supper and/or was used to collect his blood as he was dying on the cross.

Rahn was also openly gay, more discreetly anti-Nazi, and probably Jewish (though he may not have been aware of it). Despite this, he joined the Schutzstaffel (SS), Hitler’s paramilitary organization, and became the inspiration for Indiana Jones in Raiders of the Lost Ark.

Born in Germany in 1904, Rahn became obsessed with European myths and legends at an early age. He was particularly fascinated with medieval German stories about the Grail, such as Parzival (a romantic poem about a knight), Lohengrin (a story about Parzival’s son), and The Song of the Nibelungs (about a dragon slayer).

As a university student, he also became fascinated with Catharism – a Christian branch in France that was wiped out by the Catholic Church in the 13th century. He, therefore, visited France to look for clues about the Cathars and the Holy Grail.

Rahn concluded that German Christian traditions preserved many elements from its pre-Christian pagan past. He also believed that the Holy Grail was a real object that the Cathars had once held and that it remained hidden near Château de Montségur where the Cathars made their last stand.

In 1933, he published his theories in the Crusade Towards the Grail, which was well-received in Germany. It also earned him a dangerous fan, because 1933 was also the year that the Nazis took over.

That fan was Heinrich Himmler, suddenly one of the most powerful men in Germany and the one whom Hitler tasked with exterminating the Jews and other minorities. Himmler, like many high-ranking Nazi officials, was also obsessed with Germanic myths and legends.

To justify their ideals of German racial superiority, the Nazis looked to the country’s pre-Christian era. They wanted to reinvent their history and make it look greater than conventional history would have it.

Rahn’s theories supported the idea of Ariosophy – the idea that Nordics had a great and ancient past. It claims that the pre-Christian Nordic peoples were wise, philosophical, and inherently spiritual, not mere brutes like the Vikings. Such traditions were forgotten, however, due to centuries of suppression under Roman Catholicism.

Ariosophy began as an attempt to reject industrialization in favor of a simpler life by reviving Germanic pagan beliefs. But under its most influential proponent, Guido von List, it began to take on a more racial and anti-Semitic component. And Himmler was one of his followers.

As far as Himmler was concerned, Rahn wasn’t just spouting some outlandish theories. Himmler was also looking for the Holy Grail and had sponsored several expeditions into the Pyrenees to find it.

He was so sure he’d find it that he had the Wewelsburg Castle in Westphalia renovated to hold the relic.

So one day in 1933, Rahn received a telegram. It offered him 1,000 Reichsmarks (Germany and Austria’s currency till 1945) a month if he would continue his quest for the grail. But first, he had to present himself to No. 7 Prinz Albrechtstrasse in Berlin.

For a man who was always broke because he could never find full-time employment, it must have been a godsend. At least, till he realized that the man who had sent the telegram was Himmler, head of the SS.

So long as Rahn found the object, Himmler was willing to overlook the qualities that would send millions to their deaths. The openly homosexual author suddenly found himself hobnobbing with the Nazi elite.

By 1935, Rahn was under immense pressure to join the SS. Having no choice, he became a non-commissioned officer the following year. Weeks later, he bumped into a friend who was shocked to see him wearing the black uniform of the dreaded militia.

“A man has to eat,” Rahn explained dejectedly. “What was I supposed to do? Turn Himmler down?”

He knew he was living on borrowed time, however. Believing that the grail was out there was one thing. Actually finding it, was something else, entirely. He traveled throughout the country and to France, Italy, and even Iceland; but with no success.

To buy himself time and to keep the money coming, he wrote Lucifer’s Court: A Heretic Journey in Search of the Light Bringers. Published in 1937, it was an awful, rambling piece that tried to make use of poetic allegory. Some have suggested that it was a critique of Nazism as the regime became more and more brutal.

Whatever the case, Himmler loved it and ordered 5,000 copies bound in leather to be distributed among the country’s elite. Even Hitler got a copy. But when Rahn read the published version, he realized that his time was running out.

It had been edited to include anti-Semitic sentiments that he had not written. And though Himmler could overlook bad writing, he couldn’t overlook the fact that he still didn’t have the grail.

Not long after his second book was published, Rahn got drunk and was caught having sex with another man. Instead of being sent to prison, however, he was ordered to do guard duty at the Dachau concentration camp for three months.

What he saw traumatized him. In 1939, he finally worked up the courage to write Himmler a resignation letter, which the latter accepted. But one doesn’t just quit the SS, so the Gestapo gave him “the option” to committing suicide.

On 2 March 1244, the Cathars at Montségur surrendered. On March 16, their priests were burned at the stake. Many therefore believe that Rahn timed his death accordingly because his frozen remains were found in Austria on 13 March 1939. He officially committed suicide, but some claim it was a trick; that he faked his own death and continued to look for the Grail in the Pyrenees.

To grail fanatics, Rahn remains an inspiration as they continue their search for the elusive cup. And while most people have forgotten about him, the legend of the grail continues in works like Dan Brown’s The Da Vinci Code and Indiana Jones.