In the Marshall Islands, that small idyllic chain of tropical paradises, there exists a small atoll that stretches out some 80 km. The sand and coral islands that compose the atoll comprise less than six square kilometers of land and never rise more than five meters above the vast Pacific Ocean around it.

Today, the Marshallese call it the Enewetak Atoll. But when U.S. troops landed on its tiny islands packed with Japanese troops, it was known by them as Eniwetok Atoll.

The Marshall Islands were once a German colony before being granted to Japan after World War I. They represented the outer ring of Japanese island defenses in the Pacific during World War II. But after significant loses in the Solomon Islands in 1942 and 1943 and continued hard fighting in New Guinea, the Marshall Islands were poorly garrisoned, with more troops concentrated in places like the Mariana Islands, key to the defense of the Japanese Homeland.

America was looking for island bases, so that they could launch bombing raids on Japan. The Marshall Islands were the first dominoes that needed to fall. If the U.S. controlled the Mariana Islands, they could run bombing missions right over the Japanese mainland.

Rear Admiral Monzo Akiyama had concentrated the bulk of his force on several islands. The U.S. Navy had long since cracked the Japanese Imperial Navy’s code, they knew which islands these were and elected to attack the less well-guarded islands and atolls first. The first point of this campaign was the Kwajalein Atoll in the central Marshall Islands, which fell in just a few short days. The next step was the Battle of Eniwetok, about 530km to the northwest.

There were some 3,500 Japanese troops stationed on Eniwetok, mostly on the three largest islands of Engebi on the North side and Eniwetok and Parry on the southeast side. Two regiments, from the 22nd Marines and 106th Infantry, under the command of Brigadier General Thomas E. Watson, were to storm the beaches of each island and root out the dug-in Japanese.

On February 17th, 1944, bombardment of the Atoll commenced. The next morning at 8:43 AM, men from the 22nd Marines landed on Engebi. They secured the island within the day, but Japanese troops were resisting them until well into the following week.

Though it was a relatively quick battle, landing on a small island with enemies hidden in spider holes and pill boxes presents plenty of challenges. The 22nd lost 85 men with a further 166 wounded.

The Americans faced a committed enemy in the Japanese, who were willing to fight to the death. They knew no help was coming, that they were considered expendable, that their duty was to delay the Americans and inflict as much death on the enemy as possible. And so they did.

When men from the 106th Infantry landed on Eniwetok Island after a light bombing, crouching in the surf and clinging to the steep shore they began a much longer fight than the previous skirmish. Steep bluffs inhibited larger equipment coming to shore and progress was slow. Their commander Watson, tried to speed things along by landing the 22nd’s 3rd Battalion, but then the troops had to stop for the night.

The next day, the attack was renewed and U.S. troops were able to secure most of Eniwetok Island that day. Strong resistance by Japanese troops in the North of the island lasted well into the next day. On Eniwetok Island, 37 U.S. troops were killed and 94 wounded.

On February 22nd, it was time to take Parry Island. Watson wasn’t, however, about to repeat the slow takeover of Eniwetok and this time he had the navy force bombard Parry Island, with over 900 tons of explosives from the USS Tennessee and USS Pennsylvania and from field artillery on Eniwetok Island to the South and howitzers on the minuscule Japtan Island to the North.

Steady bombardment on Japanese positions allowed the 22nd Marines to advance onto the island. Japanese soldiers dug into spider holes gave them hell here, killing 73 and wounding 261. The island was secured by nightfall, but, as always hidden Japanese soldiers sprang out to fight well into the next day.

In total, 3,380 Japanese troops were killed at Eniwetok Atoll and 105 were captured. Though this far outweighs the 313 killed, 77 missing, and 879 wounded of the U.S. troops, it was a harrowing experience nonetheless for those Americans who survived the battle.

In 2014, Time Magazine published an article marking the 70th anniversary of the Battle of Eniwetok. The article concentrated on the photography of George Strock, whom the magazine had employed to photograph the battle. Strock was among the first to wade through the surf and climb up the beaches. The images he captured of U.S. troops taking fire as they came ashore and clearing out spider holes with flamethrowers among the palm trees decimated by artillery fire are profoundly striking. These images will help to preserve the memory of the battle for many years to come.

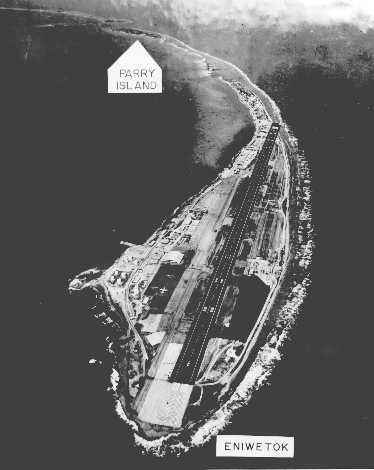

Eniwetok Atoll was quickly put to use by U.S. forces who built two airstrips, a seaplane station, and several buildings for general purposes such as medical care and recreation. It was an important forward base for the assault on the Mariana Islands and often had several hundred ships stationed in its waters.

Between 1948 and 1958 the U.S. performed 43 nuclear tests on the Atoll, including the first test of a hydrogen bomb. After a radiation clean-up project that cost around $239 million, the Atoll was declared safe for habitation once more in 1980. Today, about 850 people inhabit its islands.

By Colin Fraser for War History Online