Paul Robinett spent six months on the battlefront of WWII, first as a colonel and then as a general. During that time, he fought in almost every significant American engagement in North Africa.

A skilled horseman, Robinett had started out in the cavalry. He took part in the 1924 Olympics and trained General Patton. With tanks replacing cavalry as the striking edge of warfare, he became a tanker.

Arrival in Africa

In November 1942, American forces invaded North Africa. They attacked territory held by Vichy France. As deputy to Brigadier General Lunsford Oliver, Robinett was in charge of the units landing west of the city of Oran.

Robinett’s landings were not strongly opposed, as some others were. It was characteristic of the Operation Torch landings. American troops were spread out over a wide area, facing uncertain responses from the French, some of whom joined them while others fought back.

Robinett and his men marched toward Oran and the airfields south of the city.

Outside Tunis

The first major confrontation of the campaign occurred outside Tunis. As Allied forces advanced, the Germans launched a counter-attack on December 1. It was aimed at the center of the Allied lines.

Robinett had recently been promoted to brigadier general. He rushed forward on December 2, to counter the counter-attack. He was leading elements from American 1st Armoured Division’s Combat Command B.

He found a host of problems. Allied forces at the front did not include a balanced mix of troops. As he arrived, a unit of light tanks, unsupported by artillery, had been thrown back. Inadequate command arrangements meant forces were not supporting each other. American, British, and French troops had been mixed in together without proper thought for how they would work together.

Robinett went on the defensive, holding the line while better preparations were made and troops brought up.

Mixed Messages

In January, now commander of Combat Command B, Robinett faced an even more frustrating lack of coordination. Muddled orders left him under the command of both an American general and a French one while trying to link up with British troops. His commanders spoke different languages, gave him contradictory orders, and were slow to supply the troops he needed to fulfill his objectives.

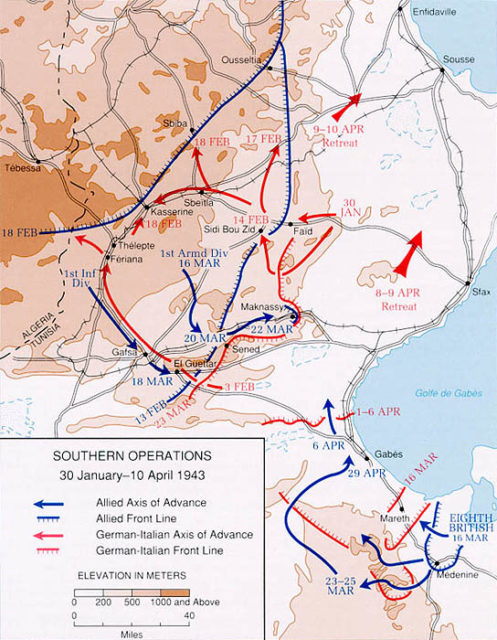

When reinforcements finally arrived, Combat Command B took part in a successful raid up the Ousseltia Valley, only to be pulled back before they had finished taking control. Robinett, who frequently annoyed superiors through his outspoken views, criticized the lack of coordination that had wasted an opportunity.

At the start of February, Robinett and his men were rushed back to the area around Ousseltia in response to a German attack. Despite a coordinated effort to take the Eastern Dorsal, the Allies were showing knee-jerk reactions to German raids, rushing troops around too late to stop them.

Due to the mingling of forces, Robinett was under British as well as American command.

Sidi Bou Zid

In mid-February, a German attack created havoc among the Allied forces at Sidi Bou Zid. Robinett was there to witness what happened but was ordered to hold back with his most experienced tanks. Combat Command B was the closest the US had to a veteran tank unit and could have been invaluable. General Fredendall did not believe that the Germans had committed their 10th Panzer Division to the attack.

On February 14, as fierce fighting took place only a few miles away, Robinett sat writing to his brother at home, sorting out a problem with income tax.

On the afternoon of the 15th, the Allies began pulling back to a defensive line at the Western Dorsal Mountains – the tactic Robinett had advised from the start.

On the 16th, Robinett was finally sent into action. Moving to hold a line southeast of Sbeitla, Combat Command B saw troops streaming in the opposite direction, back towards the Western Dorsal.

Robinett spent the day hurriedly organizing the best defensive position he could. At the front, a battalion of tank destroyers formed an outpost line. Behind them, Wadis and depressions in the earth became the hiding places for tanks. At the rear, artillery was lined up, ready to fire on the German advance.

The Germans proved more cautious than the Americans had expected. On the 17th, they took the time to assess the American positions rather than leaping to the attack. Concluding that the ground around Combat Group B would suit them best, they focused their attack there.

The attack came at just the wrong moment for Robinett. The artillery behind his tanks was changing positions and so not ready to fire. As the forward tank destroyers pulled back, a fierce fight erupted.

Due to the carefully hidden tanks, many Germans were in among the Americans before they even realized they were there. The surprise beat back the first assault.

At 1415, a second attack came. Shortly after, Robinett received orders to withdraw.

For the next three hours, he organized a careful withdrawal. Colonel Gardiner’s tank battalion bore the brunt of the fighting as they bought time for the infantry to retreat. Finally, Robinett and his men withdrew through Kasserine Pass to new defensive positions.

Last Days in Africa

Robinett fought in almost all the significant engagements of the campaign, including the frustrating fighting at Fondouk Pass.

By May, the Axis forces were in retreat. The Allies kept pushing to drive them out of Africa. On the 5th, Robinett was returning to his command with orders for an attack when artillery hit his jeep. His left leg was severely wounded. He was out of action and did not return to fight in WWII.

Just over a week later, Axis forces in Africa surrendered. All he had missed was the final stroke.

Source:

Orr Kelly (2002), Meeting the Fox: The Allied Invasion of Africa, from Operation Torch to Kasserine Pass to Victory in Tunisia