After Hitler seized Denmark and Norway in 1940, the British government became concerned about his next step, as the Nazi war machine demonstrated its might and unprecedented disrespect of the rules of warfare. Denmark, which was neutral, was invaded and conquered within a day and the British attempt to defend Norway ended up in a retreat.

The next strategic point was Iceland ― an island state in the Atlantic Ocean, which was in close ties with Denmark, claiming its independence in 1918, but still accepting the Danish king as their sovereign. Iceland was a neutral country and had no army whatsoever. The capital city, Reykjavik, was protected by 60 police armed with handguns.

Having invaded the Faroe Islands in April 1940, which were of similar status as Iceland, the British continued convincing Iceland to abandon neutrality and join the Allies. Its position, halfway between North America and Europe, was supposed to enable the British to improve their defenses against potential German submarine raids. Iceland stayed stubborn during these negotiations, claiming their right to be neutral and believing that even Hitler would respect their decision.

Though the situation was gravely serious, the British kept their cool. They decided to invade Iceland first and ask questions later. The invasion was codenamed Operation Fork. On May 4th, 1940, Alexander Cadogan, then British Permanent Under-Secretary for Foreign Affairs made an entry in his diary stating:

Home 8. Dined and worked. Planning conquest of Iceland for next week. Shall probably be too late! Saw several broods of ducklings.

Well, opposite from Cadogan – who didn’t think much of the operation -the Naval Intelligence Department had several resistance scenarios once the invasion was to commence. First of all, a number of people of German ethnicity lived in Iceland. It was expected that they might organize a guerilla force, or even stage a coup against the Icelandic government. The second scenario included a fast reaction by the Germans, who could have easily staged a counter-invasion of Iceland from the coast of Norway.

There was a force of 60 police, a possibility of Danish ships near Iceland which would certainly help a resisting population and a marooned German freighter Bahia Blanca, rescued by an Icelandic trawler. Its 62-men crew on the island at the time and they were seen as a potential threat. Especially because British Naval Intelligence already that German U-boats were stationed in Icelandic harbors and the freighter was a cover for bringing in reserve crews for the submarines.

Due to delays, the invasion which was planned to take place on 6th of May was rescheduled for 8th. Royal Marines boarded HMS Berwick and the HMS Glasgow, the two cruisers designated to take them to the island-state. The landing party included 746 Marines who were initially poorly armed. In addition to that many of them were still half-trained and many had never fired a rifle in their life. Nevertheless, they headed for Iceland, in the hope of performing a fast seizure of the island. Marines were also accompanied by members of the Naval Intelligence Department and a diplomatic mission with whom was attached the would-be consul of Iceland, Gerald Shepherd.

The Marines were seasick, as they weren’t well accustomed to traveling by ship. One of them committed suicide for unknown reasons. He would become the only casualty of the campaign.

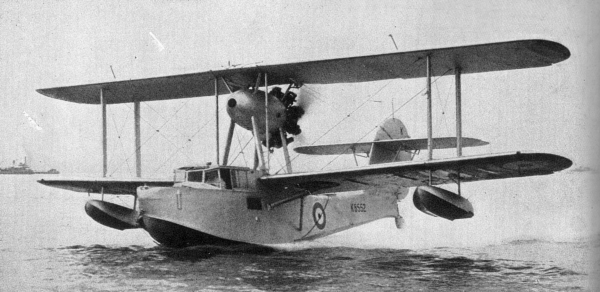

On the 10th of May 1940, a reconnaissance plane was launched from the Berwick. Even though it was warned not to fly across Reykjavik, it neglected the order. Since Iceland had no airports nor airplanes, the noise of the Supermarine Walrus reconnaissance aircraft gave away the British intentions.

The German consul was probably the most alarmed since he hurried to the coast where he saw the British ships approaching. He went home and started burning all confidential documents in his possession.

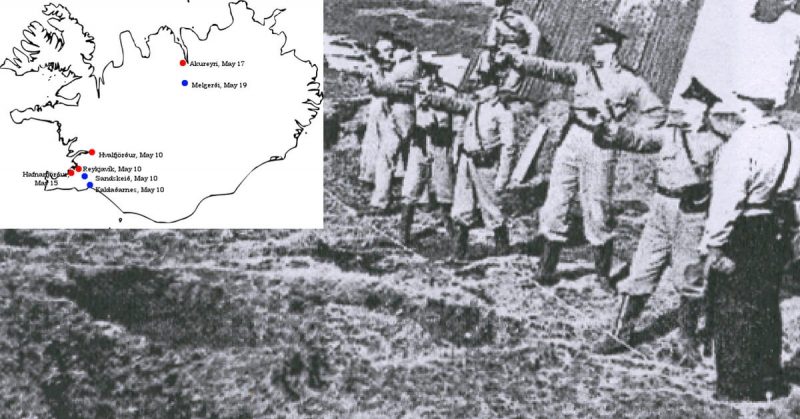

The Royal Marines were finally on the move. Two destroyers, Fearless and Fortune, joined the cruisers and started transporting the 400 Marines ashore. The ships were crowded and the men were still seasick and not in a state to act as a proper task force. A crowd was already gathered to wait for the invaders. Once they were ashore, Consul Shepherd politely asked the Icelandic police officer in front of the bewildered crowd: “Would you mind getting the crowd to stand back a bit, so that the soldiers can get off the destroyer?”

“Certainly,” replied the officer.

Reykjavik was taken without a shot being fired. The Marines hurried to the German consul’s house, where they managed to salvage a significant number of confidential documents.

On the evening of May 10th, the government of Iceland issued a protest, saying that its neutrality had been “flagrantly violated” and its “independence infringed,” but eventually agreed to the British terms. The troops stayed on the island out of fear of a German counter-attack, but it was later realized that Hitler had dismissed the notion of occupying Iceland as its strategic importance wasn’t bigger than the cost of the invasion.

The British were joined by the Canadians, and they were relieved by US forces in 1941. When the US officially engaged in WWII, the number of American troops on the island reached 30,000. This number equaled 25% of Iceland’s population and 50% of its total male population. Even though the occupation brought many economic advantages to Iceland and many infrastructural benefits such as airfields, hospitals, and roads, the local population protested against the courtship between Allied soldiers and Icelandic women.

The Icelanders called this situation simply “The Situation” (Ástandið) and the 255 children born out of these relationships “Children of the Situation”. A number of marriages happened between Allied soldiers and local women, but some men accused the women of betrayal and prostitution. Iceland spent the war in peaceful occupation and often refers to the period as the “Lovely War”. The British retreated completely after the war, and most of their facilities were turned over to the Icelandic government, but American military presence remained. The last of the US soldiers were pulled back from Iceland in 30th of September 2006.