On December 7, 1941, the Japanese launched a surprise attack on the naval base at Pearl Harbor, devastating the American forces stationed there. In the over 80 years since, a number of heroic stories have emerged. However, there are many whose daring feats are seldom spoken about. Both military and civilian, these are eight individuals whose actions at Pearl Harbor made them heroes.

First Lt. Annie Fox

When the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor began, First Lt. Annie Fox was stationed at Hickam Field, where she held the position of Chief Nurse. Caught off-guard and entirely unprepared to deal with casualties from such a large assault, she managed the 30-bed hospital for the duration of the attack. This included the six nurses who worked under her and the volunteers who’d flocked to the hospital to help with the influx of wounded civilians and US military personnel.

The hospital was located well within the area subject to the enemy bombings, with many falling within close range of the building. It got so bad that Fox, her nurses and the volunteers, concerned over the threat of a possible gas attack, were forced to wear gas masks and helmets while they worked on their patients.

Fox was the first woman to receive the Purple Heart for combat. Her citation described her actions as follows:

“[She] administered anesthesia to patients during the heaviest part of the bombardment, assisted in dressing the wounded, taught civilian volunteer nurses to make dressings, and worked ceaselessly with coolness and efficiency, and her fine example of calmness, courage and leadership was of great benefit to the morale of all with whom she came in contact.”

When the award criteria was changed to require someone be injured in combat, Fox’s Purple Heart was converted to a Bronze Star. She continued serve throughout the Second World War, eventually working her way up to the rank of major.

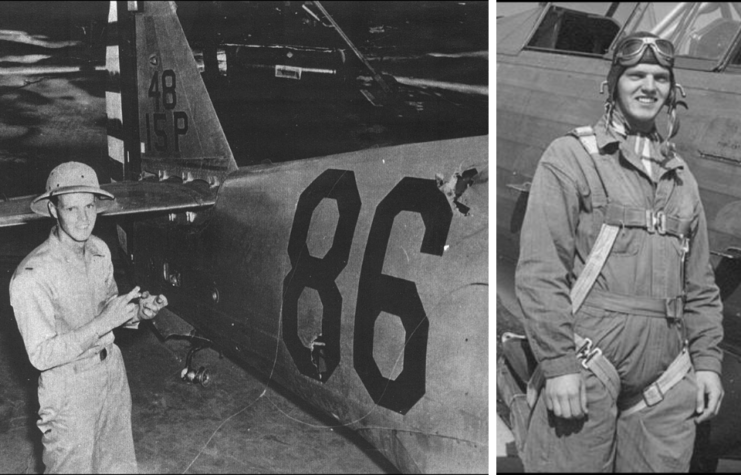

Second Lt. Phil Rasmussen

Second Lt. Phil Rasmussen of 46th Pursuit Squadron was tucked safely in bed in his barracks at Pearl Harbor when the Japanese launched their attack. Startled awake, he looked out of his window to see enemy aircraft dropping bombs nearby.

As a pilot with the US Army Air Forces, Rasmussen knew he needed to get in the air, so he strapped his pistol overtop of his purple pyjamas and ran out the door. Despite most of the aircraft in his area being destroyed, he was able to load a Curtiss P-36A Hawk with ammunition.

Rasmussen waited until there was a reprieve from the bombings and took off alongside three other pilots, all of whom were ordered to fly to Kaneohe Bay. Once there, they engaged 11 Japanese aircraft, with Rasmussen shooting down one. During the assault, his P-36A was badly damaged, and he ended up careening toward the ground in an uncontrolled dive.

Falling to roughly 5,000 feet, he managed to gain enough control to land – although, he did so without a rudder, tailwheel or brakes. Upon inspection, Rasmussen discovered his aircraft had suffered over 500 bullet holes. He received a Silver Star for his actions and served with the US Air Force until 1965.

Among the many heroes from the attack on Pearl Harbor, he and his P-36A have been commemorated in an exhibit at the National Museum of the US Air Force, unofficially titled “The Pyjama Pilot.”

George Walters

Not all the heroes at Pearl Harbor were members of the military. George Walters, for example, simply showed up for work as a crane operator at the naval base. The machine he was working in was located near the drydock that the USS Pennsylvania (BB-38), a super-dreadnought battleship, had been moved to for repairs. Pennsylvania was, understandably, a prime target for the Japanese, who soon zeroed in on the vessel.

From where Walters was sitting, he could see the attack coming. He positioned his crane in a way that helped block Pennsylvania, while also alerting her crew. Instead of moving into position and running to safety, he stayed where he was. Some sources indicate he used his vantage point to indicate to the crewmen where the aircraft were coming from by moving the boom of his crane, while others say he used it as a weapon to try and knock the Japanese pilots out of the sky.

Walters is credited with helping down 10 different aircraft. He and his crane were eventually targeted and a 500-pound bomb was dropped from above, knocking him out. He made a full recovery, and worked at the shipyard for another 25 years.

Chief Boatswain Edwin Hill

Edwin Hill served as the Chief Boatswain onboard the USS Nevada (BB-36), the only battleship to attempt an escape from Pearl Harbor. He was heavily involved in the movement of the ship that day, releasing her from her moorings. Accounts say Hill leaped from the back of Nevada and climbed up onto the dock while the attack raged around him. He then jumped back into the water and climbed onto the ship as she tried to escape.

Evidently the only moving vessel – and a large one at that – Nevada was an easy target for the Japanese. In an effort to prevent the ship clogging up the harbor mouth, her captain decided to beach her. Hill was responsible for dropping the anchor, but was killed, along with 46 other crewmen, when bombs hit Nevada near where he was standing.

A number of survivors later credited Hill with saving their lives by ordering them to take cover during the heavy bombing. He was posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor for his actions, proving to be one of the many heroes of the attack on Pearl Harbor.

Ensign Herbert Jones

Ensign Herbert Jones was stationed onboard the USS California (BB-44) when the Japanese attack was launched. He’d just relieved another junior officer on deck when the ship was damaged by a torpedo that took out the mechanical hoist used to load the anti-aircraft guns.

Jones quickly got to work, organizing sailors to hand deliver the ammunition. During this, California suffered another hit, grievously injuring Jones. The bombing caused the battleship to take on water, and she was in danger of going up in flames at any moment due to the sheer amount of burning oil in the water.

The order went out for the vessel to be abandoned. However, when two comrades tried to drag Jones with them, he responded, “Leave me alone! I’m done for. Get out of here before the magazines go off.” US Marine Corps Pvt. Howard Haynes was one of the men and believed Jones’ orders saved his life.

Jones was posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor for his actions in organizing the ammunition chain and for refusing to leave California, despite her impending destruction. The USS Herbert C. Jones (DE-137) was named for him in 1943.

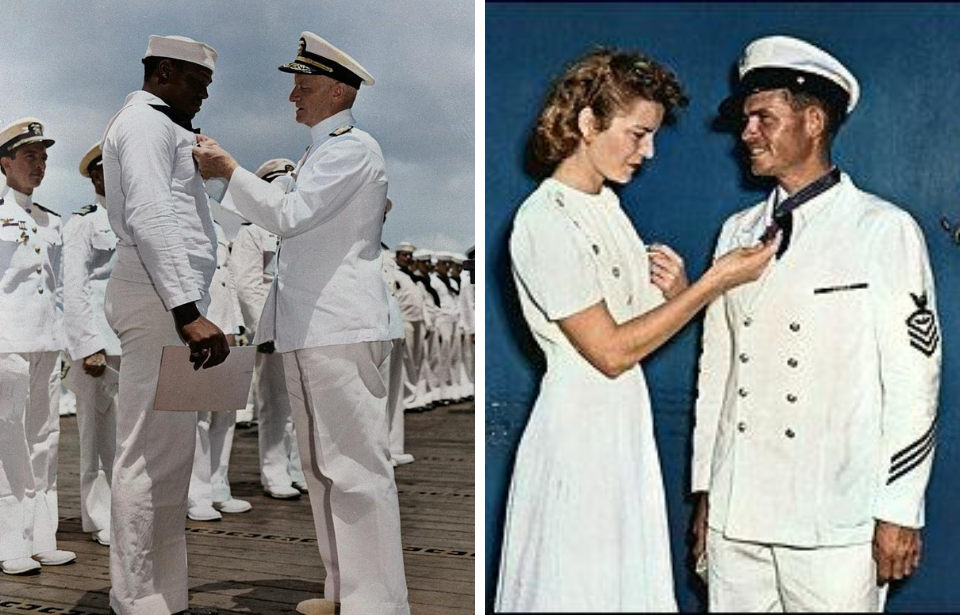

Cook Third Class Doris Miller

Cook Third Class Doris Miller worked onboard the USS West Virginia (BB-48) and had just served breakfast when the attack on Pearl Harbor began. He was assigned to a battle station, but upon reporting there found it had been destroyed by a torpedo. Instead, he was sent to man a Browning .50 caliber anti-aircraft gun by two other sailors.

Miller was given a crash course on how to operate the weapon, having never been formally trained, and began shooting. He manned the gun until he was out of ammunition, shooting down a number of enemy aircraft in the process. When he could do no more, he aided in the movement of injured soldiers, an action which helped save many lives.

Miller received the Navy Cross for his actions, but didn’t live to see the end of the Second World War. He was killed in action (KIA) while serving onboard the USS Liscome Bay (CVE-56) in 1943. Following the Battle of Makin in the Gilbert Islands, the vessel was struck by a torpedo fired from the Japanese submarine I-175, detonating the ship’s munitions and causing her to sink.

The USS Miller (FF-1091) was named in his honor, as will a new Gerald R. Ford-class aircraft carrier.

Lt. Cmdr. Samuel Fuqua

Lt. Cmdr. Samuel Fuqua was enjoying breakfast onboard the USS Arizona (BB-39) when air raid sirens sounded. When he emerged on the quarterdeck, he was met by enemy fire and knocked out by a Japanese bomb that had been dropped nearby. He eventually regained consciousness and began directing the men around him to put out the fires on deck.

Despite the rank he began the day with, Fuqua became Arizona‘s senior officer after more than 1,000 crewmen were killed when their ammunition magazines exploded. He took the role in stride, as described by another crewman, “I can still see him standing there, ankle deep in water, stub of cigar in his mouth, cool and efficient, oblivious to the danger about him.”

By this point, Arizona was sinking, and Fuqua managed her evacuation, being one of the last to abandon ship. He and two officers then commandeered a boat, which they sailed through the harbor to pick up whoever they could. Fuqua was awarded the Medal of Honor for his actions, and he stayed in the US Navy until 1953, reaching the rank of rear admiral.

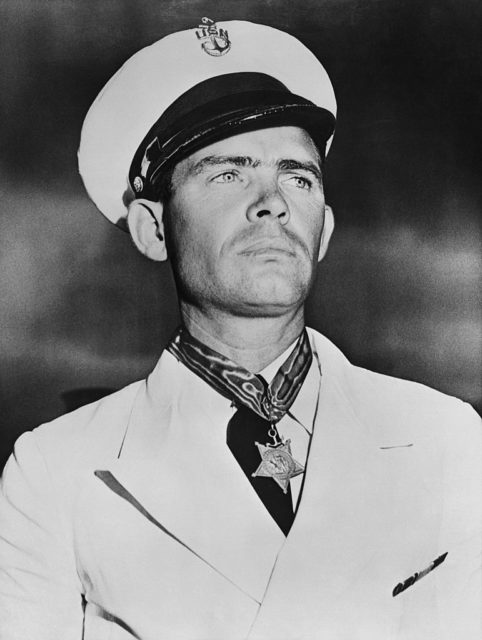

Chief Petty Officer John Finn

Chief Petty Officer John Finn was lying in bed with his wife in the early hours of the morning on December 7, 1941 when he heard the enemy aircraft descend upon Pearl Harbor. He quickly drove to Kaneohe Bay, where he took control of a .50 caliber machine gun and dragged it out into a clearing with a good view of the air.

Over the span of two hours, Finn almost consistently shot at the attacking enemy aircraft. Although he held his ground, he suffered 21 wounds from bullets and shrapnel, one of which broke his foot. Another made him lose the use of his left arm. Of his actions defending against enemy aircraft, he later said, “I can’t honestly say I hit any. But I shot at every d**n plane I could see.” He was treated for his injuries when the attack subsided, and returned to duty the very same day.

More from us: The Devastating Failure of Japan’s Mini Submarines at Pearl Harbor

He received the Medal of Honor for his actions, survived the war and lived to be 100 years old. Upon his death in 2010, he was the oldest living Medal of Honor recipient. He also held the distinction of being he last living US Navy awardee from the Second World War and the last from the attack on Pearl Harbor.