American President Franklin Roosevelt spoke words that would last for decades, for centuries when he decreed that December 7, 1941 would forever be a day that lived in infamy. On that sleepy early morning, the United States found its military planes, ships, soldiers, sailors and airmen under attack from Japanese forces – forces that struck from the air, the sea, and seemingly every possible direction.

Caught completely unaware, the U.S. military scrambled to save its outpost at Peal Harbor, but the damage left in Japan’s wake was great. Although the U.S. regrouped and developed its most powerful weapon, the atomic bomb, to defeat Japan in the years that followed, those bombings were not the only attacks conducted in the name of retaliation by American forces.

On February 1, 1942, the United States launched its very first act of retaliation against the nation of Japan for the surprise attacks committed at Pearl Harbor: The Marshalls-Gilberts raids. A series of tactical air and naval attacks conducted in the Marshall and Gilbert Islands, these strikes were planned and carried out against the Imperial Japanese Navy. An effort that was undertaken in the hopes of causing damage like that of the Pearl Harbor attacks on this newest enemy.

Though the Japanese inflicted great destruction upon the American Navy resting quietly along the shores of Oahu, the U.S. intended to reinstate its powerful position as a world leader by striking Japan in multiple aircraft carrier attacks.

The Attacks Begin

At the time of the raids, the Japanese kept both naval and air forces in the Marshall and Gilberts Islands, commanded by Vice Admiral Shigeyoshi Inoue and Rear Admiral Eiji Goto. Under the command of Vice Admiral William Halsey, Jr., the United States warships carried out two separate raids, each one led by a separate carrier-designated task force.

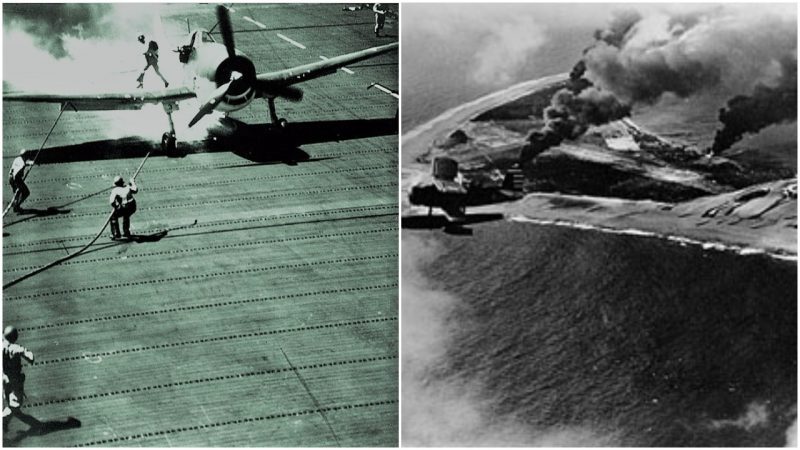

The aerial attacks, charged to Task Force 17 and led by the command of Rear Admiral Frank Jack Fletcher, launched its attack from the deck of the aircraft carrier the USS Yorktown. These airmen aimed their attack upon the small islands of Jaluit, Mili, and Makin (later known as Butaritari). As the airmen flew above these Japanese-held locales, launched from the deck of the Yorktown, rained damage down upon the enemy’s naval posts – by the raid’s end, three Japanese aircraft were destroyed.

However, the U.S. itself felt the impact of the raid, as three planes and a floatplane were shot down by the Japanese. The military effort was considered a moderate success; no great damage was caused, and no irreparable harm was inflicted upon the Imperial Japanese Navy.

The second of the two raids was conducted by aircraft of Task Force 8, which was directly under the command of Vice Admiral Halsey himself. Taking off from the aircraft carrier USS Enterprise, these American forces carried out air attacks on the islands of Kwajalein, Wotje, and Taroa – and shared results similar to the first raid performed by Task Force 17.

Both cruisers and destroyers fired on the islands, the bombing raids and shelling of three of the Japanese naval garrisons sank three warships, damaged others, and destroyed 15 enemy aircraft.

Unfortunately, in a manner similar to that of the first raid, the U.S. forces were not lucky enough to escape damage. In response to the American attack, the Imperial Japanese Navy hit and damaged the USS Chester with the use of an aerial bomb. Additionally, six planes that took off from the Enterprise were shot down when Japanese fighters took off to fend off the U.S. raiders. Upon completing their assigned tasks, the U.S. Task Forces 8 and 17 immediately left the Marshalls-Gilberts Islands, leaving the Japanese to recover.

More Battles Followed

Although it appears at first glance that the U.S. made little military advancements in its first strike against Japan after Pearl Harbor, history does not decree that America and its forces failed. According to Admiral Chester Nimitz, who accompanied the efforts of the Marshalls-Gilberts Raids in early 1942, the attacks were executed exactly as planned.

Though these raids held little long-term impact, and left the Japanese only slightly worse off than before the raids, the United States considered its efforts both planned and carried out as hoped. Because, as Admiral Nimitz remarked, it was anticipated that the U.S. forces would have to make almost blind attacks on the Japanese forces at Marshalls-Gilberts Islands due to limited intelligence data.

While the Americans quickly retreated and pulled their forces from the Japanese-occupied area, this military maneuver was planned well ahead of time. The U.S. did not retreat because it did not leave the damage anticipated in its wake, nor because it failed to inflict the same destruction as the Japanese did at Pearl Harbor.

Instead, the two island raids struck Japan with great surprise – after Japan planned its total decimation of American naval forces at Pearl Harbor, the enemy nation did not think the U.S. would be able to regroup and reorganize so quickly after those December attacks. So, when Japan’s leaders discovered there was one flaw in their attack – all of the U.S. aircraft carriers were out at sea, not waiting in Oahu during the events of Pearl Harbor – they forgot just the impact of the American Navy.

Japanese leaders presumptively assumed that the U.S. would retreat inward, seeking to defend its precious and few remaining naval resources for many months.

Instead of assuming a defensive stance, the United States rose from the midst of Japan’s havoc. While the Marshalls-Gilberts Raids did not gain any territory, any political advancements, nor any significant destruction against Japan’s navy, it did increase the morale at home among Americans.

The public itself felt proud and restored, believing its military and government was capable of fighting back against Japan soon after Pearl Harbor’s horrors. Attacking even this small of a Japanese outpost gave U.S. military forces crucial experience combating the enemy nation and its air tactics – and taught the Japanese just how weak their defenses in this island area were.

It was the Marshalls-Gilberts Raids that showed the Imperial Japanese Navy, and Japan itself, just how quickly the Americans could rebound despite the devastation caused on December 7th.

However, it was the Marshalls-Gilberts Raids that also brought the Japanese and U.S. into battle again in future days; those quick and sudden small attacks led to the crucial Battle of Midway only a few months later.