It is a matter of historical fact that Nazi Germany committed truly horrific crimes against humanity during WWII. Germany and 14 other countries have even made Holocaust denial illegal in various ways.

According to the official version, the bulk of the atrocities was carried out by the dreaded Schutzstaffel (SS – the Protection Squadron). It was the SS which enforced the racial-purity laws, formed a distinct combat unit within the military, ran the concentration camps, and controlled the populace through fear.

The Wehrmacht (and the army, navy, and air forces), on the other hand, were for the most part simply soldiers who did what they were told. They were on the frontlines and had little to do with the atrocities committed by the SS. In the Wehrmacht’s defense, there are plenty of anecdotal stories highlighting the extreme contempt they held for the SS.

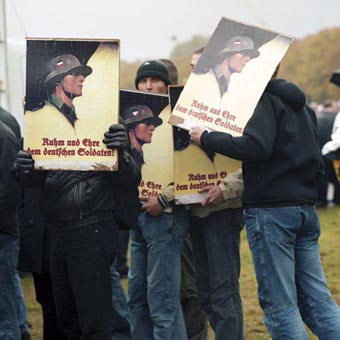

So when The Hamburg Institute for Social Research first exhibited Crimes of the German Wehrmacht. Dimensions of a War of Annihilation (1941-1944) in 1995, there was a public outcry in Germany. It was so controversial that they had to cancel the exhibit, and were only able to display it again in 2001. Even then, the outcry was immense.

While the rest of the world sees no difference between the SS and the Wehrmacht, many Germans do.

Among those who fail to see that difference are the residents of the Dutch town of Putten in Gelderland. It began with the failure of Operation Market Garden – the airborne attempt by the Allies to enter Germany’s Ruhr region which began on September 17th, 1944.

Some of the Allied soldiers who parachuted in got separated and landed in different parts of the Veluwe – now the biggest national park in the Netherlands. The Germans managed to repel the invasion, but they also knew that many Allied soldiers were stuck in German-occupied territory.

Dutch resistance to the occupation was fragmented because of the confiscation of radios and the termination of telephone communications. While some groups were able to take in downed Allied parachutists and helped them to get back across the border, others acted on their own.

At around midnight of September 30th, 1944, a Dutch resistance group led by Ab Witvoet, was in a truck near the Oldenallerbrug Bridge when a car approached them. In that car were two German Officers and two Lance-Corporals of a regular army formation.

The Dutch resistance fighters in the truck were armed with a machine gun, but before they could open fire, one of the men on the road panicked and began shooting with a Bren light machine gun. Someone on the truck tried to shoot the truck’s mounted weapon, but it misfired, causing confusion among the resistance fighters. The German officers fired back, hitting only one Dutchman, Frans Slotboom, who died from his wounds the following day.

German Corporal Over-Lieutenant Eggart was hurt and taken prisoner, while the other three escaped. One of these was Lieutenant Otto Sommer. Though seriously injured, he was able to make his way to a farmhouse where the farmer and his wife were able to tend to his wounds. The farmer then managed to stop a German convoy who took Sommer to a hospital where he later died.

As for the captured Eggart, his injuries made him a serious liability to his captors so they had an argument as to whether or not they should just kill him. Witvoet had vanished, leaving the group in a panic, so they decide to set the officer free.

But Sommer’s alarm had gotten through and the countdown had begun. General Friedrich Christiansen, the commander of the Wehrmacht in the Netherlands, ordered Major General Fritz Fulfriede to go to Putten and make an example of it. Troops stationed at Utrecht, Amersfoort, and Harderwijk were sent to the town to seal it off.

By 6:30 AM, farmers in the surrounding area were ordered into the town. During the roundup, one woman and six men tried to run away and were shot dead. By mid-afternoon, Putten’s police chief was ordered to put forward ten hostages, but he refused. Instead, they chose a town clerk, and demanded that he submit 30 names. The clerk also refused.

Even non-residents who were in the wrong place at the wrong time were ordered into Putten. 28-year-old Gerardus Johannes, who lived in a neighboring village, was bicycling into Putten to visit his girlfriend when he got caught up in the Wehrmacht dragnet.

The surrounding communities were not spared either. Nineteen-year-old Jannes Priem, a resident of Putten, was with his brother at the border of Wells and Nijkerk when Wehrmacht soldiers ordered them to Putten. After being forced to walk 5 kilometers to Putten, he, his brother, and several other men were made to line up against the walls of the Old Church.

The women and children were sent into the Old Church, while the men were all assembled outside on the cul-de-sac of Harderwijker Straat. Jannes thought he’d be shot, but the Wehrmacht began sending those younger than 18 into the church. He tried to lie about his younger brother’s age, but the soldiers didn’t buy the act.

Some of the elderly and infirm, as well as women with babies, were allowed to go home on the condition that they hang white sheets outside their windows. By noon, the men were brought to the town’s school in front of the market where they spent the night outdoors.

The following morning, trucks arrived to take away 661 men to Amersfoort. Thirteen managed to get away, while another 58 (mostly elderly men) were sent back to Putten on account of poor health. The rest were sent to various concentration camps throughout Germany, most went to Ladelund, a subcamp of Neuengamme.

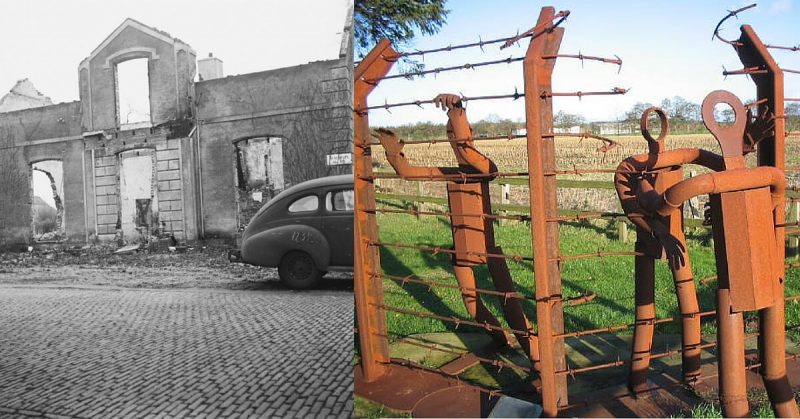

As further reprisals, the German and Dutch SS set fire to 105 houses, all but obliterating Putten from the map.

By Haren Noman, Theo van / Anefo – Fotocollectie Anefo. Nationaal Archief, Den Haag, nummertoegang 2.24.01.05, bestanddeelnummer 901-0092., CC BY-SA 3.0 nl

Jannes died on 22 August 2013, but Putten hasn’t forgotten its trauma. Germans, meanwhile, are still struggling with the idea that their precious Wehrmacht weren’t quite the heroes they’d like to believe.

After the war, only 48 men returned to Putten. Five died shortly after, while a few remained crippled for life because they were kept in cages where they couldn’t move. Jannes was among the survivors, but he was so emaciated that even his family didn’t recognize him.