There were many extraordinary events in the Battle of the Atlantic, the contest between the Germans and the Allies for control of the sea lanes, from 1939 to 1945. It usually involved the Germans waging submarine warfare against Allied shipping, especially British Shipping at first. One of the strangest incidents in the ‘Battle of the Atlantic’ was when a German submarine surrendered to a British plane.

This is the real story of the capture of the U-570, not what Hollywood made of it!

In 1941, the submarine U-570 went into service for the German Navy. It was based in Norway and was under the command of Captain-Lieutenant Hans-Joachim Rahmlow. Though an experienced naval officer, this was Rahmlow’s first time in charge of a submarine. His First Watch Officer (second-in-command) and Second Watch Officer were likewise inexperienced in submarines while the rest of the crew were raw recruits.

On August 23, the B-Dienst intercepted British communications regarding a large group of Allied merchant ships off Iceland. Sixteen U-boats were ordered to sink them all, and the following morning, the U-570 set off to do just that – her very first war patrol. It was a trap. The British suspected that their communications had been compromised, so the message was a decoy to see if the Germans would bite.

By August 27, the U-570 had been in rough seas for several days, and everyone was suffering from seasickness. Some were so badly ill that they became completely bedridden. Desperate for some respite, Rahmlow ordered the submarine close to the surface, which was against regulations and contrary to his training. In the clear waters off Allied-occupied Iceland, it was clearly visible from the air.

Which was how British Sergeant Leslie “Les” Bathy Mitchell of 269 Squadron spotted it. Based in Kaldaðarnes, Iceland, Mitchell was flying his Lockheed Hudson bomber on a routine patrol when he saw the U-570 just below the surface. Grinning, he flew low and activated his depth charges, but the bomb-racks jammed and wouldn’t release. Furious, he called out the U-boat’s position and stayed in the area to make sure his squadron got it right.

Rahmlow wasn’t aware of this. Whether because of inexperience or because he was far too sick to care, he didn’t bother looking into his periscope to see if the coast was clear. At 10:50 AM, the U-570 breached the surface… right below 269 Squadron Leader James Thompson. Once he got over his shock, Thompson circled back and flew low as he made a beeline toward the submarine – hoping and praying his bomb-rack wouldn’t jam.

Rahmlow had just stepped onto the bridge when he heard the plane’s engine through the submarine’s hull. He ordered the vessel to dive, but it was too late. Thompson released four 250-pound depth charges, and this time, the mechanism did not jam – they plunged into the water at an angle of 30° to the vessel’s rear. The U-570 sped forward as it dived, avoiding a direct hit.

Thompson’s last depth charge also missed… but it didn’t matter. It detonated some 10 yards away from the submarine. The combined force of the explosions slammed into the U-570, but the last one did the trick. The submarine almost rolled over then settled. The vessel’s power failed, and this was followed by water leaking into the vessel. In the engine room, acid leaked from battery cells and mixed with water, forming a gas. Thinking it was chlorine gas (it wasn’t), the engineers panicked.

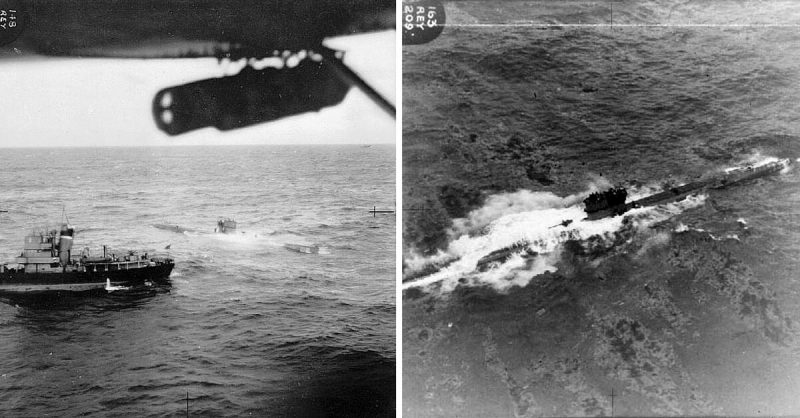

Rahmlow ordered them to surface while signaling the crew to don life-jackets and get up to the conning tower. Thompson thought they were trying to man their deck guns, so he made another pass and began firing, but stopped when he saw them wave a white flag. Not that it mattered. The waves were so high that anyone who stood on the submarine’s deck would have been washed off. That obviated the lifeboats and life-jackets as well.

On the bridge, Rahmlow radioed his superiors while his crew began destroying their Enigma machine and dumping code books overboard. In his panic, he didn’t bother encoding the message, which was picked up by the British who ordered all available ships to the scene. The Germans also ordered U-boats to the area to help. The U-82 responded, but Allied bombers forced it to leave the area, for its own safety.

The HMT Northern Chief finally reached the U-570 at 10:50 PM and threatened to kill everyone, including those in life-rafts and life-jackets, if the submarine was scuttled. The Germans replied that they couldn’t even if they wanted to, and pleaded for rescue as they chucked overboard what they could to keep from sinking. Northern Chief replied that help would arrive the next day and trained lights on the U-570 till more British ships arrived.

As August 28 dawned, things got worse. The Germans demanded immediate rescue, while the British insisted on first securing the submarine. While the yelled at each other, a Norwegian Allied pilot flew over. Not understanding the situation, he dropped bombs on the U-570. Thinking the Northern Chief was a German rescue vessel, he fired and the ship fired back till the HMS Burwell radioed it to stop.

Then the weather grew worse. The British tried to attach a tow-line to the submarine, but the Germans kept missing. Thinking they were just being difficult, the Burwell fired warning shots, wounding five Germans but killing none.

With much difficulty, an officer and three sailors from the trawler HMS Kingston Agate reached the submarine using a liferaft. After a quick search had failed to find the U-boat’s Enigma machine, they attached a tow line and carried out the transfer of the five wounded men and the submarine’s officers to the Kingston Agate. The remaining crew were taken on board HMCS Niagara, which by this time had come alongside the U-boat.

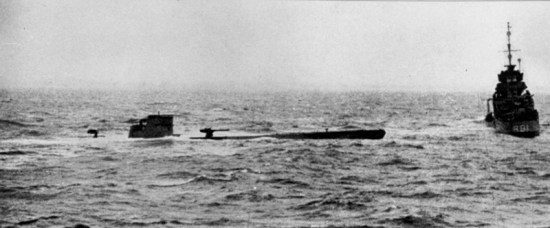

The ships began slowly sailing to Iceland with the U-570 under tow, and with a relay of Hudsons and Catalinas constantly patrolling overhead. They arrived at dawn on 29 August at Þorlákshöfn. There, the submarine was beached as she had been taking on water and was thought to be in danger of sinking.

After repairs in Iceland, she sailed, on her own power, with a prize crew to England. There she was repaired and then meticulously tested to determine her capabilities.

She provided both the Royal Navy and the United States Navy with significant information on German submarines, and carried out three combat patrols with a Royal Navy crew, becoming the only U-boat to see active service with both sides during the war.

She was decommissioned from active service in February 1944. She saw some use as a target, to determine the damage caused by depth charges in full-scale trials. After surviving these experiments, she was to be towed by the Royal Navy rescue tug HMRT Growler from Chatham to the Clyde for scrapping. But on 19 March 1944 her tow–rope broke in gale-force winds and, driven by wind and waves, she ran aground near Coul Point, on the west coast of Islay, Scotland. Growler was unable to refloat the submarine, and she was abandoned.

Graph was partially salvaged and scrapped in 1947. Some remains of HMS Graph still remained visible at low tide on the rocks near Sligo beach in 1970, with the pressure casing of the conning tower and periscope tube clearly visible today, the remains of the wreck lie in about 20 ft of water.

To date, the U-570 is the only submarine known to have surrendered to a plane!