The American relationship with the Soviet Union during WWII (1939-45) was an exceedingly strange one. For some two decades, the United States and the Soviet Union (USSR) had been adversaries. The avowed purpose of the Soviet Union was to accelerate what they saw as the world’s inevitable “progress” towards a global communist state.

The United States, for its part, had opposed the Soviet regime as antithetical to the American way of life since its inception following the Russian Revolution in 1917. America had even sent troops to the Murmansk region and the Russian Far East in an abortive effort with its allies to support Russian enemies of the communist regime.

In the opening stages of WWII, the US and the United Kingdom were not sure whether or not Stalin would join Hitler in his drive for a totalitarian conquest of the world. The surprise announcement of the Nazi-Soviet non-aggression pact in August of ’39 and the subsequent Soviet invasion of Finland caused serious doubts in London and Washington about the intentions of the USSR. These doubts were only allayed after the Nazi invasion of the Soviet Union in June 1941.

Suddenly for the Soviets, it was as if the past two years of cooperation between themselves and Hitler hadn’t even existed. Soon after Hitler ordered the invasion of Russia, they were asking both Britain and the USA for massive amounts of military aid.

Only the old saying “The enemy of my enemy is my friend” made Britain and the US willing to fulfill many of the Soviet demands. Without his troops fighting on the Eastern Front, Hitler’s troops would be ready to jump the English Channel, take the Suez Canal, etc.

We know the rest of the story: the Allies defeated Hitler after a concerted effort of trust and mutual understanding, right? Well, not exactly…

British, Canadian, American and other Allied sailors delivering goods to Murmansk were kept under surveillance and not allowed to leave the port area. Allied convoys delivering oil, trucks and other goods into Soviet Central Asia were given the same treatment. Many of the men who risked their lives bringing aid to the Soviet Union were left with a big question: “With friends like these, who needs enemies?”

In addition to some unfriendly behavior (and there were certainly exceptions – but woe to the Soviet citizen who got too close to the foreigners: charges of being a spy in the pay of the capitalists often followed), Soviet engineers worked tirelessly to gain access to some of the secrets that the Allies held close to their chest.

The Russians didn’t need help with tanks – they had arguably the best all-purpose tank of the war in the T-34. Cannons? When Berlin was surrounded in 1945, it is estimated that the Soviets had close to 10,000 guns aimed at just that one city. Planes? The Russians had decent fighters by wars’ end, but poor pilots. The Americans gave them P-39 Airacobras, but that was because American pilots hated them.

What the Soviets lacked was a strategic bomber force. They saw first hand the damage done to German cities by the air forces of Britain and the United States and realized that they were far behind in the development of modern heavy bombers. By 1944, the best bomber on the face of the planet was not flying over Germany, however. It was raining destruction on Japanese conquests and the Japanese home islands on the other side of the world. This was the famous Boeing B-29 Superfortress.

Fortunately for America, heavy bombers had been in the production pipeline before war broke out. These were the B-17 Flying Fortress and the B-24 Liberator. Though both planes played a not insignificant role in the Pacific, they certainly played a decisive role in the European Theater. Though the B-24 had a larger payload and longer range than the B-17, it was decided an even bigger bomber with a larger payload and much larger range was needed.

This idea became the B-29, whose basic design was developed in 1939. The first flight of the true B-29 (i.e., not an experimental version) took place in the fall of 1942. Orders had already been placed for the plane, which, though in development before the US entry into the war, was in a state of constant evolution. The B-29s that began to bomb Japan in 1944 were a generation ahead of the B-17 and 24.

Each plane cost over six hundred thousand dollars to build. By wars’ end, the cost of building the almost four thousand Superfortresses was three billion dollars – more than the US had spent researching and building the atomic bomb. Over one hundred thousand parts went into the construction of the plane.

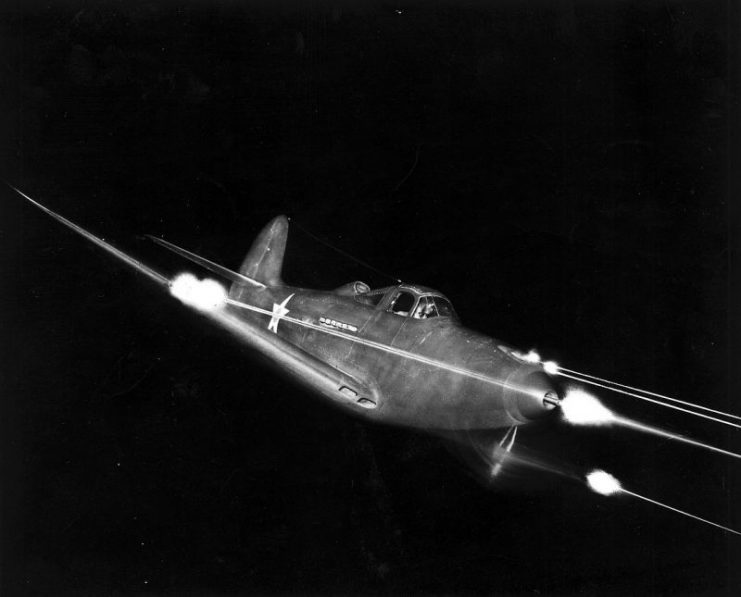

The B-29 was the first plane to use remote-controlled guns, navigation and bombing aids, and mechanisms on such a scale and in so advanced a manner.

The plane had a crew of eleven. Its maximum payload was 20,000 pounds, and it was possible for it to carry more in specially modified editions. For self-defense, the B-29 carried from eight to ten .50 caliber machine guns, with two in the rear that were sometimes replaced by a 20mm cannon. Variants of the plane used different configurations.

The bombers’ maximum range was over three thousand miles carrying a payload, and it could fly at over 350 mph if needed. Perhaps best of all, its service ceiling was nearly 32,000 feet – out of reach for most Japanese planes and guns.

By wars’ end, the B-29 had essentially burned every major Japanese city to the ground, with two obvious exceptions: Hiroshima and Nagasaki. The Superfortresses Enola Gay (Hiroshima) and Bock’s Car (Nagasaki) dropped the atomic bombs which ended the war.

Joseph Stalin and Soviet aircraft designers wanted a B-29…badly.

They got more than one. They got five. These planes landed in the Soviet Far East after bombing Japanese targets in Manchuria and of course Japan itself. Making emergency landings due to damage, weather, and loss of fuel, the B-29 crews were eventually sent home via Iran.

Their planes (or the remains of them in the case of the one that had to crash land) stayed with the Soviet Union, where their engineers were ordered to examine the US plane in the hopes that they could reverse engineer them.

The only Soviet heavy bomber had been built in 1936 and was virtually useless. To the men of the Red Army Air Force (more properly the “VVS”, the Russian acronym for “Military Air Forces), the B-29 was almost from another planet.

Engineers were tasked with duplicating every aspect of the B-29 in developing a Soviet version. So attentive to that detail were they, that a typewriter left by an American airman on one of the bombers was included as standard equipment on every Soviet copy of the plane. This was despite any knowledge of the usefulness of a typewriter on the plane or lack thereof.

From the outside, the Soviet copy, the Tupolev Tu-4 looked virtually identical to the B-29. The length of the fuselage and the wingspan were the same. The speed was the same. The Soviet version had a higher ceiling, but that came at a price: the aluminum used by the Soviets was thinner (not as protective, but cheaper). The payload was virtually identical as were the placement and number of defensive armaments, though the Soviets added air-to-air missiles to their later models.

It took the USSR more than two years to get their version off the ground, debuting in 1947. In 1949, the Soviets exploded their first atomic weapon, which was carried by the Tu-4. Production of the plane ended in 1952. Eight hundred and forty-seven had been built in five years.