A British territory north of Spain, Gibraltar is a beloved tourist destination that experiences naval dockyard actively by the British Royal Navy. Lesser known are the vast networks of tunnels beneath the area, spanning approximately 34 miles, with some dating back to the 1700s.

King’s, Queen’s and Prince’s Lines

While caves within the Rock of Gibraltar may have been used by Neanderthals, the first intentionally-dug tunnels came into existence shortly after its capture by the British in 1704, primarily for use as military fortifications.

Known as the King’s, Queen’s and Prince’s Lines, they took much of the century to finish, as the British were defending against Spanish and French assaults during the Thirteenth (1727) and Great Siege of Gibraltar (1779-83).

Over a thousand meters of interconnected tunnels

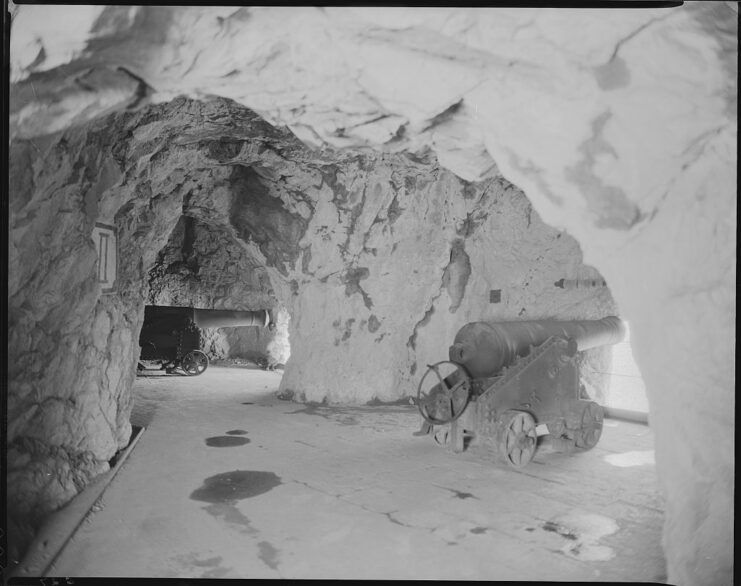

Throughout the sieges, the British carved out the initial true tunnels and “galleries” within the Rock of Gibraltar. Resembling artificial cave systems, they were used to position artillery. By the late 1700s, approximately 1,200 meters of interconnected tunnels had been excavated, linking the various defensive lines that had been established earlier.

These spans encompassed several notable structures, such as the Windsor, Queen’s Union, Upper Union, Lower Union, Prince’s, King’s and Queen’s Galleries.

Gibraltar’s significance as a naval base continued to grow

By the late 1800s, Gibraltar’s significance as a naval base grew, leading the British to expand their underground infrastructure. New tunnels were dug to facilitate access to quarries and for ammunition storage. A notable addition during this period was the Dockyard – also known as the Admiralty Tunnel – which became one of the most significant developments.

Admiralty Tunnel

The Dockyard spanned the entire expanse of the Rock of Gibraltar, facilitating seamless access between the active dockyards and the quarries supplying stone. Moreover, between 1898-1915, five underground reservoirs were constructed, to mitigate concerns regarding water supply instability.

Instability in Europe prompts increased construction on Gibraltar

Starting in 1936, during the Spanish Civil War and with the rise of the National Socialist German Workers’ Party, the British built hospitals and air raid shelters within the Rock of Gibraltar.

Civilians were also evacuated, turning the territory into a military stronghold.

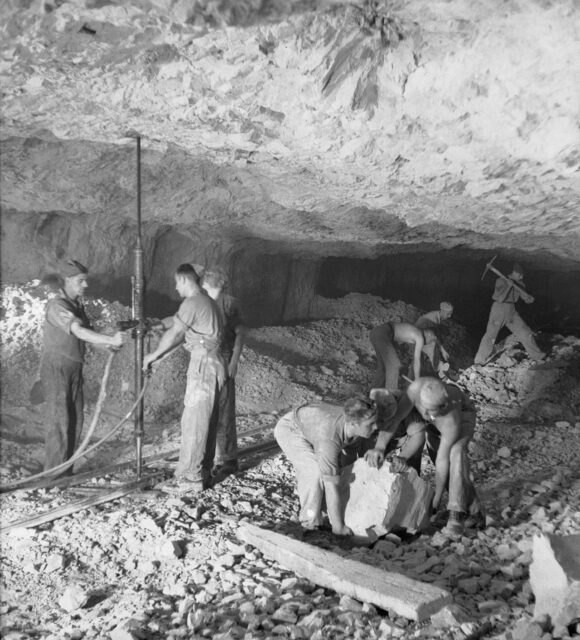

Outbreak of World War II

With the outbreak of World War II, more tunnels were excavated, with the intention of serving as military barracks and storing equipment. The British and their allies stationed at Gibraltar constructed an underground city with facilities ranging from a power station to a bakery. These enhancements enabled Allied troops to be accommodated underground for up to 16 months, if necessary.

‘Stay Behind Cave’ and Operation Tracer

One of the most unique tunnels from this era remained concealed for over 50 years. Known as the “Stay Behind Cave,” it was dug as part of the covert Operation Tracer and was intended as a refuge for British spies, in case Gibraltar was captured by the enemy.

Between 1936-39, two miles of tunnels were constructed, and from 1939 until the conflict’s conclusion, 18 additional miles were added, expanding the total network to 25 miles.

Tunnel expansion continued following World War II

Following the conclusion of the Second World War, the expansion of the tunnel systems in Gibraltar continued, albeit at a reduced pace compared to earlier years.

During this period, several tunnels were primarily used for storage purposes or as reservoirs. The final one beneath the Rock of Gibraltar was completed in 1967, and the last group of specialized tunnel workers was disbanded the following year. By then, the tunnels stretched over 34 miles in total length.

Rock of Gibraltar, today

More from us: Tököl Airbase Played a Major Role in Germany’s War Machine – That Is, Until the Soviets Took It Over

Today, there’s little necessity for military fortifications on Gibraltar, as the presence of the British Royal Navy has significantly decreased. However, the tunnels haven’t been entirely abandoned; many of them are now accessible for visitors to explore. Among the most popular are those dating back to the Great Siege and a select few from the Second World War that are open to the public.