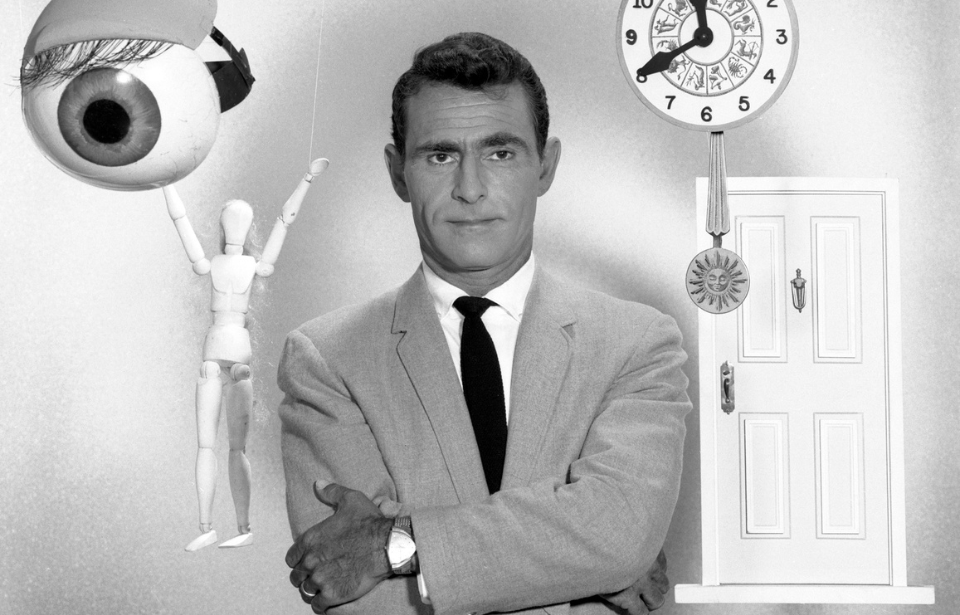

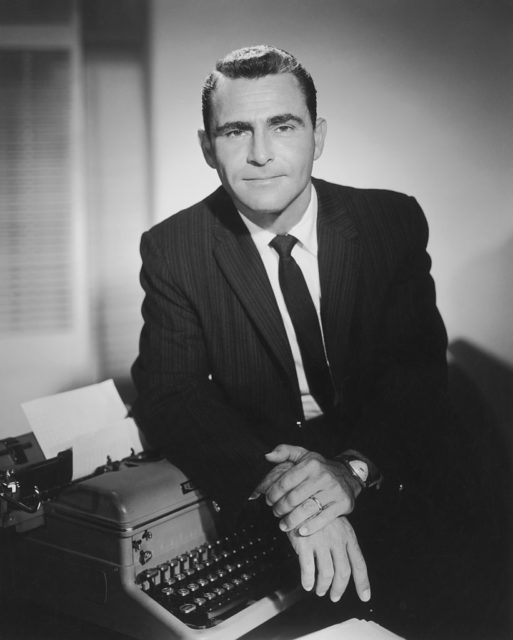

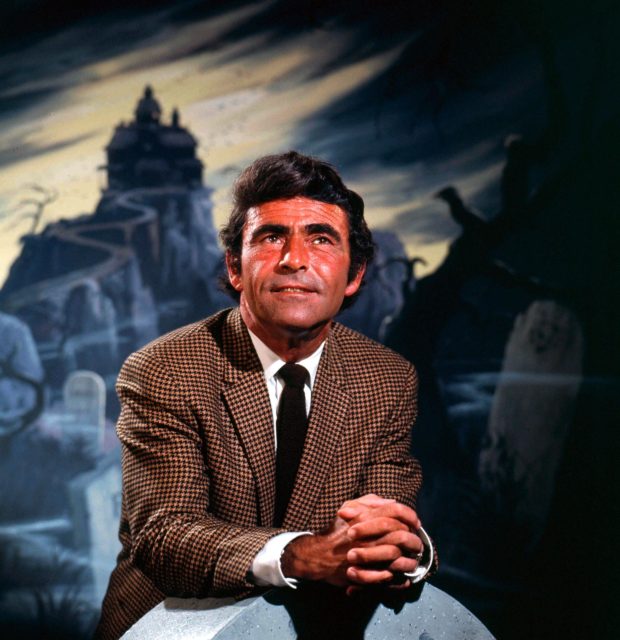

Rod Serling was among the most prolific television writers of the 20th century. The mastermind behind the cult classic anthology series, The Twilight Zone (1959-64), he was known for incorporating his own experiences into the show’s scripts. Much of what he included traced back to his time in the US Army during the Second World War – in particular, his service as a paratrooper in the Pacific Theater.

Rod Serling’s early passion for writing

Rod Serling was born on December 25, 1924 in Syracuse, New York to a Jewish family. Just under two years later, they moved to Binghamton, where the future television writer spent the majority of his childhood.

While in elementary school, Serling was dismissed by his teachers, who saw him as a lost cause. It wasn’t until seventh grade that his teacher, Helen Foley, encouraged him to sign up for a public speaking extracurricular. This led him to join the debate team and, later, his high school’s student newspaper. Through the latter, he’s said to have “established a reputation as a social activist.”

Ever since he was a child, Serling had shown an interest in writing and radio. According to his older brother, Robert, the younger Serling would spend hours in the basement, acting out movie and pulp magazine dialogue on a makeshift stage their father had built. He also spent a lot of time listening to horror, fantasy and thriller productions on the family’s radio set.

Enlisting with the US Army

By his senior year of high school, Rod Serling had been accepted into Antioch College in Yellow Springs, Ohio. However, by this time, the Second World War was in full swing, and he wanted to do what he could for the war effort. Given his Jewish heritage, he wanted to drop out of school and enlist with the US Army Air Forces as a tail gunner aboard a Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress, so he could travel to Europe and fight the Germans.

Despite his wishes, Serling remained in school until graduation on the advice of his Civics teacher. While awaiting the end of his education, he used his position with the school newspaper to urge his fellow students to join and support the war effort.

The day after graduation, in 1943, Serling enlisted with the US Army. He was sent for basic training at Camp Toccoa, Georgia, and after four months was sent to Fort Benning to undergo jump training, having decided to serve as a paratrooper. After earning his Silver Wings, he was assigned to the 511th Parachute Infantry Regiment, 11th Airborne Division under Col. Orin D. “Hard Rock” Haugen and Gen. Joseph May “Joe” Swing.

Throughout his training, Serling had to prove he was worthy of a spot in the military. Rather short, he had to convince officials to allow him to train as a paratrooper, and frequently picked fights with tankers, infantrymen, fliers and other paratroopers. This led him to pursue boxing, fighting 17 bouts as a flyweight. He was known for his Berserker-style hits, but, despite his efforts, he failed to win the coveted Golden Gloves.

The 511th Parachute Infantry Regiment is sent to the Pacific

In April 1944, Rod Serling and the 511th Parachute Infantry Regiment received orders to travel to California, signaling they were being sent to the Pacific Theater to aid in the fight against Japan. A month later, the paratroopers were sent to New Guinea, where, for months, they sat around, without any interaction with the enemy. During this time, comedian Jack Benny visited them while on a USO tour. Along with writing one of the skits, Serling also performed a small on-stage role.

On November 20, 1944, during the Battle of Leyte, the 511th finally saw combat – however, not as paratroopers. Instead, they served as light infantry, securing the area where divisions had previously landed. From there, they advanced 30-40 miles along narrow trails in the Philippine jungle, becoming bogged down for two weeks on a crag nicknamed Hard Rock Hill.

Given his penchant for ignoring orders and not having “the wits or aggressiveness required for combat,” Serling was reassigned to the 511th’s demolition platoon, nicknamed the “Death Squad” due to its high casualty rate, under the leadership of Sgt. Frank Lewis. By the time action on Leyte had finished, the paratrooper had suffered two injuries, including one to his kneecap, which affected him throughout the remainder of his life.

Heavily casualties during the Battle of Manila

On February 3, 1945, Gen. Douglas MacArthur deployed the 511th Parachute Infantry Regiment as part of the Battle of Manila. Col. Orin D. Haugen led the men as they made their poorly-executed jump from a Douglas C-47 Skytrain onto a large area on Tagaytay Ridge. They subsequently met up with the 188th Glider Infantry Regiment, 11th Airborne Division and marched into Manila.

The paratroopers were met with little resistance until they reached the city, where Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) Vice Adm. Sanji Iwabuchi had his 17,000-strong force waiting for them, with orders to fight to the death. Over the next month, the 511th and 188th moved block by block through Manila, taking portions of the city from the Japanese and suffering a casualty rate of 50 percent.

Their efforts were celebrated by locals, who threw parties for the Americans. During one such celebration, the Japanese launched an attack, killing a number of servicemen and civilians. Despite the enemy fire, Serling ran toward the stage to rescue one of the performers. Other military action Serling undertook during this time included him shooting and killing a Japanese soldier while engaging in combat at Rizal Stadium.

Rod Serling’s discharge from the US Army

Following the Battle of Manila, the 511th Parachute Infantry Regiment was sent to Okinawa to serve as part of the American occupation force in Japan. While members of the 1st Cavalry Division claim to have been the first US military force to land in Japan, it was actually the 11th Airborne Division.

In 1946, Rod Serling was honorably discharged from the US Army, after which he worked at a rehabilitation hospital while he recovered from his wounds. For his service during the Second World War, he received a number of honors, the most notable of which were the Bronze Star, the Philippine Liberation Medal with one service star, the Army Presidential Unit Citation and the Purple Heart.

Pursuing a radio career

Following his service, Rod Serling used the GI Bill to fund his enrolment in the physical education program at Antioch College. While there, he worked with the campus radio station, writing, directing and even acting in a number of programs. This led him to volunteer with WNYC in New York, later returning to the station as a paid intern as part of his work study. This, along with working part-time as a parachute tester for the US Army Air Forces, helped him supplement his income.

It was during his college years that Serling won his first writing accolade, being chosen as the winner of the annual scriptwriting contest held by the Dr. Christian radio program. He subsequently attempted to make a living selling freelance scripts to radio stations, but failed due to issues within the industry.

In 1950, following his graduating with a Bachelor of Arts in Literature, Serling found work as a continuity writer for WLW in Cincinnati, Ohio. He continued his freelance efforts, selling several scripts to the station’s parent company, Crosley Broadcasting Corporation. However, he believed radio wasn’t living up to its potential and began looking toward the evolving medium of television.

Rod Serling finds television success

Rod Serling became a writer for WKRC-TV, in Cincinnati, writing testimonial advertisements for questionable medical products and scripts for a local comedy duo. He began re-writing his radio scripts for television and saw some success, prompting him to leave the station and pursue being a freelance writer full time.

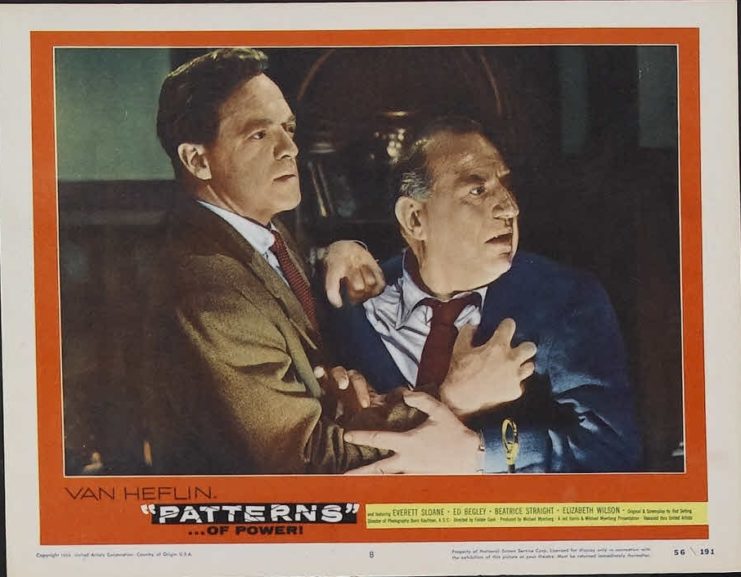

In 1955, Kraft Television Theatre aired a program based on one of Serling’s scripts, titled Patterns. The special centered around the power struggle between a veteran corporate head and a young up-and-coming executive being groomed to replace him. Instead of firing the young man, the former asks him to aid in a campaign to push aside his competition. According to Serling, he modeled the elder character after his former commander, Col. Orin Haugen.

Patterns became an immediate hit and led to Serling writing another television special, Requiem for a Heavyweight. This, too, received critical acclaim, so much so that it was adapted into a film in 1962, which starred Mickey Rooney, Anthony Quinn, Julie Harris and Jackie Gleason.

The Twilight Zone

The more his writing was accepted by television studios, the more Rod Serling grew frustrated with the amount of censorship forced upon him. He held strong views on a number of hot-button social issues, which were tamed by the studio big wigs who commissioned his scripts.

This frustration led him to submit “The Time Element” to CBS, intended to be the pilot episode for The Twilight Zone. Instead, the company used the script for a new show produced by husband and wife duo, Lucille Ball and Desi Arnaz. It told the story of a man who suffers from vivid nightmares about Pearl Harbor and seeks the help of a psychiatrist, only for the twist to be that the patient actually died during the Japanese attack and the psychiatrist was the one having the dreams.

Upon airing, the episode received largely positive reviews, prompting CBS to green light Serling’s show.

The Twilight Zone premiered in October 1959. Airing for five season, the series mixed horror and fantasy with Serling’s own life experiences. A number of Vintage Hollywood names guest starred in the anthology, including Carol Burnett, Buster Keaton, Ron Howard, Robert Redford, Julie Newmar, Robert Duvall, Burt Reynolds and Charles Bronson, among many others.

Despite drawing critical acclaim and having a loyal fanbase, The Twilight Zone failed to bring in more than moderate ratings, leading it to be canceled three times during its original run. When the third cancellation occurred, Serling refused to fight it, having grown tired of the series.

Rod Serling’s later ventures weren’t as successful

Following the cancellation of The Twilight Zone, Rod Serling tried his hand at other shows. In 1965, the American Western series, The Loner (1965-66), premiered on CBS. The show, which ran for only one season, followed William Colton (Lloyd Bridges), who moves to the American West after serving as a Union Army cavalry captain during the Civil War.

The executives at CBS wanted Serling to write more action and violence into the show’s scripts, but he refused, prompting them to hire others screenwriters. This didn’t help The Loner‘s ratings, and the series was cancelled after only 26 episodes.

A few years later, NBC aired Night Gallery, the film precursor to what would become a three-season television series that told macabre and horror stories. Serling served as host and major contributor, but it differed from his previous ventures in that he didn’t wish to retain creative control over the scripts. He wound up regretting this, as, by the third season, the majority of his contributions were being heavily edited or outright rejected.

Night Gallery (1970-73) was cancelled after 43 episodes.

Bringing personal views to the small and big screens

Rod Serling’s experience during the Second World War impacted his political and personal views, which, in turn, influenced his writing. Once eager to fight on the front, the Army veteran was an outspoken anti-war activist by the time the US was involved in the Vietnam War.

He used his wartime experiences as the basis of a number of episodes of The Twilight Zone, which served as a vessel for Serling to speak about prejudice, war, bigotry and the fear of nuclear war, among other issues. While the episode most people talk about in regard to this is “The Purple Testament,” about an American lieutenant fighting in the Philippines, there are other examples:

- “24 Men to a Plane” recounts Serling’s first combat jump into Manila. The leader in the first aircraft orders his men to jump too soon, causing the other aircraft to mistakenly drop their men.

- “The Rack,” which aired as part of the United States Steel Hour, tackles the question of whether a soldier should be charged with a crime for cooperating with enemy forces in times of duress. In it, a US Army captain is put on trial for having urged his fellow prisoners of war (POWs) to cooperate with their captors.

- “Time Enough At Last” centers around a bookworm who supports a disastrous nuclear attack because it’ll free him from his day-to-day activities and give him more time to read his books.

- “He’s Alive” covers the ubiquity of fascist policies and follows the rise of a racist figure, portrayed by Dennis Hopper. The German Führer appears in the episode as a ghost-like figure.

- “The Shelter,” set during the height of the Cold War-era panic, shows what happens when a dinner party host refuses to let their friends into the family’s bomb shelter after warnings emerge over a possible incoming nuclear strike.

- “The Monsters Are Due on Maple Street” is a visual representation of the distrust many Americans felt during the Red Scare, with suburbanites feeling unable to trust their neighbors.

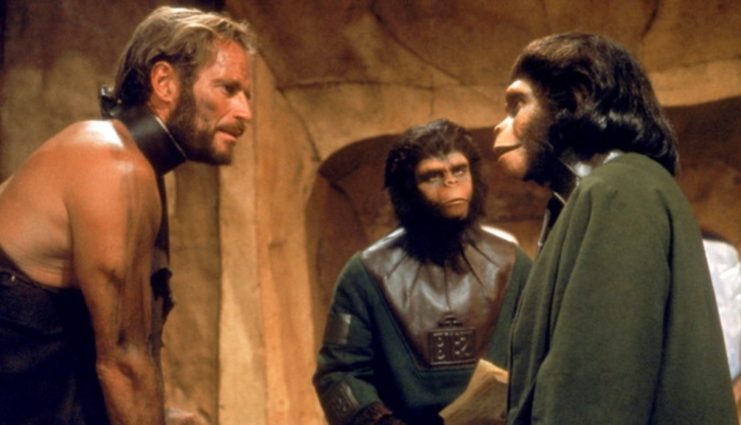

These themes also appeared in the handful of films Serling helped write, including Planet of the Apes (1968), which addressed animal rights, racial prejudice and the nuclear apocalypse, and Seven Days in May (1964), a nuclear disarmament thriller.

Rod Serling’s return to radio and untimely death

In 1973, Rod Serling made his return to radio as host of The Zero Hour, an anthology series featuring tales of adventure, suspense and mystery. The show lasted two seasons. Following this, he made his final appearance on radio with the 48-hour-long Fantasy Park concert. Airing on nearly 200 radio stations across the country, it featured performances from a number of popular bands and artists, including The Beatles.

Alongside his work on television and radio, Serling had made a habit of teaching week-long college seminars. During a break in filming The Twilight Zone, he held a one-year teaching job at his alma mater, educating students on writing and drama, and covering the “social and historical implications of the media.” After retiring from life in the media, Serling made teaching his main focus, taking a position at Ithaca College in New York.

A life-long smoker, Serling is said to have gone through three-to-four packs of cigarettes a day. This resulted in him suffering a heart attack on May 3, 1975, for which he was hospitalized. Two weeks after his released, the famed scriptwriter suffered a second, prompting doctors to agree to undergo a risky open-heart surgery. During the 10-hour procedure, Serling had yet another heart attack and died two days later. He was 50 years old.

More from us: Henry Fonda Served In the US Navy During WWII – He Didn’t Want to ‘Be a Fake In a War Studio’

Rod Serling was buried at Lake View Cemetery in Interlaken, New York. Over the course of his decades-long entertainment career, he was the recipient of a number of awards, included a Peabody, a Golden Globe and six Primetime Emmys. Following his death, he was inducted into both the Television Hall of Fame and the Science Fiction Hall of Fame, and in 1985 received a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame.