On June 22, 1941, Germany invaded the USSR. It was a move that came as a shock to the Soviets, but less so to the British. For some time, they had been gathering evidence that Germany was about to attack her ally. They had tried to get the Soviets interested in discussing this but had no luck.

It was a moment that reflected both the political and the military intelligence challenges facing Hitler’s opponents in World War Two.

The State of USSR Military Intelligence

Soviet military intelligence in 1941 was not what it had once been. Under the Tsarist regime of 25 years before, Russian staff included highly skilled cryptographers. The Tsarists were well placed to both encrypt their own messages and decrypt those of their enemies.

Much of this specialist skill had been lost in the turmoil of the Revolution and the early Soviet era. Although Soviet intelligence gathering was active in other ways, it lacked the most vital tool in the British arsenal.

The State of British Military Intelligence

The British, building on work by the Polish, had cracked Germany’s highest level military encryption – Enigma. Together with other decryption work by the Royal Navy’s Y Section, it gave them tremendous insight into what was being said by the Germans.

In some ways, British intelligence gathering was still limited. The swift fall of France and evacuation of the continent had left Britain without useful contacts in mainland Europe. Every area of British intelligence, including cryptography, was hurrying to learn skills neglected between the wars.

British intelligence work was flawed and sometimes a struggle. With the Enigma information, they created deeper insight than anyone else could acquire.

Stalin and Military Intelligence

The flaws in the USSR’s intelligence work were accentuated by the man at the top – the General Secretary of the Communist Party and dictator of the country, Joseph Stalin.

Stalin took a hands-on approach to military intelligence. He liked to see the raw material gathered by his agents.

While this might seem like a good idea, it was not. Stalin filtered this intelligence for evidence that matched his preconceptions. He ignored the insights of professionals better qualified to understand military intelligence.

Convinced it was not in the interests of the German Führer Adolf Hitler to break the Molotov-Ribbentrop pact between the two countries, Stalin refused to consider the idea that Germany might invade the USSR.

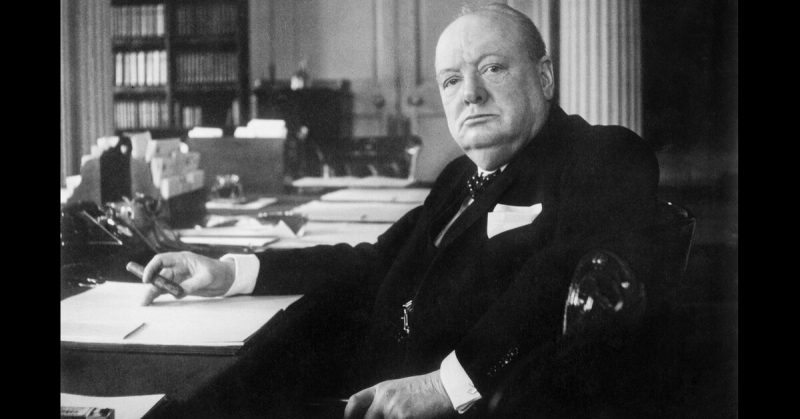

Churchill and Military Intelligence

British Prime Minister Winston Churchill had a similar attitude to military intelligence. It caused problems in the early days of the war, as Churchill charged ahead based on his limited understanding of the information, rather than trust the experts.

Unlike Stalin, Churchill broke his habit. By 1942, he allowed military intelligence chiefs to guide him.

In 1941, either because of guidance or due to a fortunate coincidence of prejudice and reality, Churchill believed that Germany would invade the USSR.

Churchill Tries to Change Stalin’s Mind

Churchill first sought to convince Stalin of the danger from Hitler in May 1940. At the time, the British did not yet have evidence of a planned invasion of the USSR. Churchill, looking at the strategic balance of the continent, judged that Hitler would eventually turn his eyes east.

While sending the new Ambassador, Sir Stafford Cripps, to Moscow, Churchill reached out to Stalin about Hitler. There was no direct accusation, but instead a more diplomatic approach, suggesting they discuss Europe’s problems.

It was obviously in Britain’s interests to create dissension between Germany and the USSR. If Germany were fighting elsewhere, it would take pressure off Britain. Stalin, knowing this, was not willing to take the bait.

British Uncertainty

Over the next year, evidence reached the British that Churchill was right. The Germans were preparing to betray their Soviet allies.

The first hints came from contacts on the ground, particularly among the Polish resistance. In early 1941, they saw evidence of preparations for the invasion. In March this was backed up by decrypted Enigma signals about the movement of troops.

In April and May came more substantial evidence. Decryption showed a steady flow of German troops to the east. There was still no diplomatic hint of trouble between Germany and the USSR. It made the intelligence hard to interpret. Was Hitler moving these troops to put pressure on Stalin in secret negotiations? Was it about the fighting in Yugoslavia and Greece?

Even as evidence mounted for Churchill’s theory and the idea of an eastern front looked likely, many British analysts remained uncertain.

The Wrong Sort of Paranoia

Ultimately, the USSR’s unwillingness to listen to British warnings came from two failures of judgment.

The first was Stalin’s paranoia. The history of wars between Europe’s dominant powers, together with the ideological differences between the Communist USSR and the rest of Europe, meant there was no reason for him to trust Britain or Germany. He had to decide which way to jump. Was he more distrustful of German military intentions or British diplomatic maneuvers?

Being more suspicious of the British was natural. Hitler had made a greater effort to befriend the USSR. Stalin had more in common with the self-made German dictator than the aristocratic British establishment.

Ultimately, it was the wrong call.

The Problem of Believing the Unbelievable

The other misjudgment was one made by every nation facing Hitler. Britain, the USSR, and their contemporaries all expected him to behave rationally. It was in the best interests of Germany and his regime to keep the USSR friendly while he dealt with Britain.

However, Hitler was not rational. He had deep-seated beliefs in the need to destroy Communism and obtain land for Germans to inhabit. His commitment to these causes overcame everything.

Gathering and analyzing military intelligence was difficult in World War Two. Convincing others to act on it was even more challenging. Predicting the actions of a fanatic, that was a trick that few other than Churchill could manage.

Source:

Ralph Bennett (1999), Behind the Battle: Intelligence in the War with Germany 1939-1945.