War History Online Presents a Guest Blog from Author Miguel Vargas – Caba

A Flight by the Crews of the 392nd ODRAP in search for the Aircraft Carrier “USS Saratoga”

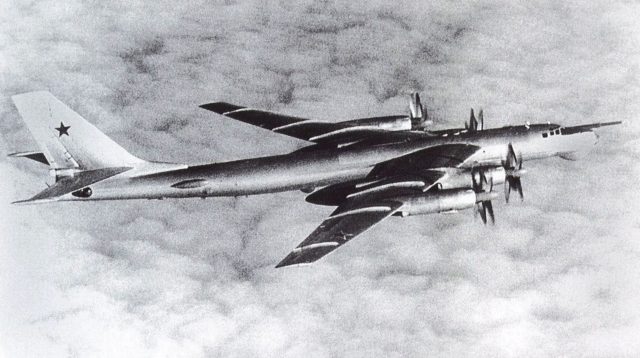

In the late seventies, regular flights by the long-range reconnaissance aircraft Tu-95RTs (NATO: “Bear D”) of the 392 ODRAP to Cuba had already become quite routinary. But since the task had always been fairly complex and important, and its fulfillment in isolation from the regiment, far from the Russian shores, the selection of crews received special attention. The aircraft commanders and navigators were selected from a level of training usually not lower than 1st Class. The qualifications and skills of all the other members of the aircrews were taken into account, as well as their psychological readiness to fly in long flights. The team spirit of the crews was also checked in the air.

The total length of the flight route from the airfield at Olen’ya, Kola Peninsula, USSR, to the airfield at San Antonio de los Baños, 20 kms. SW of Havana, Cuba, was 10,150 km, and the flight time, taking into account the prevailing winds, was usually 15:40 to 16:00 hours. They always flew at night, so as to land in Cuba in the morning hours, before strong cumulus and thunderstorm clouds developed. The flights were over the Barents and Norwegian Seas, and over the Eastern, Central, and Western Atlantic Ocean. Major disruptions to the flights were mostly winds and jet air currents. During the flights, the Soviet pilots had to cross frontal clouds. When entering the jet stream they faced the strong turbulence of air masses, and buffeting for a long time while flying in the clouds over the ocean, without any landmarks. At the same time, they tried to save fuel by flying across the ceiling “at a distance”, that is, constantly selecting the flight mode at which they got the minimum fuel consumption per kilometer. The art of such flights was thus learned and utilized by almost all the crews of the regiment, and this saved them not just once, giving them the necessary additional kilos of fuel at the right time. In addition, the Cold War over the ocean was in full swing, and they often had to meet with U.S. and NATO fighters, which not always behaved amicably and peacefully.

Sometimes the crews had to perform tasks, from the outcome of which could depend the future of their flying careers. About one such case tells us Col. (ret.) Pavel Pavlovich Burmistrov, who flew in the 1970s as navigator in the crew of Squadron Commander Major Nikolai Gordeyevich Fedotov.

Intercept Saratoga! – A Photo for Fidel Castro

December, 1977. After completing a long non-stop night flight, and meeting the sunrise over the ocean while approaching the island of Cuba, the crews of Majors Nikolai Gordeyevich Fedotov and Ghennady Nikolayevich Simachov landed safely at the airport of San Antonio, 40 kilometers from Havana. At that time I was flying as navigator in Major Fedotov’s crew. Flying with him was easy and interesting. After completing all the necessary formalities to carry out on arrival and a short hop in a bus, our crews were accommodated in a comfortable villa in Casablanca, one of the oldest and most beautiful areas in Havana, drowning in greenery. To their credit, the Cubans were able to provide for the flight crews’ R&R. Any problems about this were immediately solved.

On the second day, came to us in the villa Colonel V. I. Dubinsky, a former commander of the 392nd ODRAP, and our flight director in Cuba. We were always glad to communicate with him. He informed the crew about the state visit to the island of Cuba taking place at that time, by the Commander in Chief of the Soviet Navy, Admiral Serghey G. Gorshkov. Along with him, was the Commander of the Naval Aviation, Colonel-General Mironenko. They decided matters of naval cooperation between the two friendly nations. Among those considered were the issue of basing some units of the Soviet Naval Aviation at the Cuban airfields.

From the beginning of the visit to Cuba, Tu-95RTs landed in the island, so the Commander of the Navy ordered the Commander of the Naval Aviation to show Cuban leader Fidel Castro, how effective was the work of Soviet aircrews when carrying out sorties in their search for warships of the U.S. and NATO naval forces along the U.S. east coast, in the Bermuda Triangle, and in the Central and Western Atlantic Ocean.

At that time, a major US capital ship, the multitasking aircraft carrier “USS Saratoga” was returning from a tour in the Mediterranean Sea together with its carrier group, composed of six surface warships. Our crew was ordered to prepare for a flight to search and discover the group in order to take aerial photographs of the aircraft carrier. The task was familiar to us, but the level of interest in its implementation in this occasion left a definite impression in us.

The crews immediately began preparations for the flight. According to the fleet intelligence reports, the alleged objective area had been identified. The navigators planned the flight route, taking into account the estimated position of the aircraft carrier at the time of its discovery. The weather at the time of departure and throughout the flight route was favorable, the weather conditions would allow us to perform the task. The pre-calculated flight duration, taking into account the wind, was about 14 hours, each aircraft taking 82 tons of fuel. The flight was scheduled to start at night, at 3:00 hours local time, so as to arrive at the area of detection in the morning, and confidently produce photographs of the aircraft carrier at a low altitude. Cumulus and strong cumulus clouds at that time of the day were still underdeveloped, and could not prevent the taking of photographs. Typically, high-quality images were always obtained when taking pictures of ships from a height of not less than 300 meters. If we went below 300 m, the flight itself produced an effect, besides giving the body extra adrenaline, but more often than not led to photographs of the vessel that did not show the deck, which spoiled the result of the photographic reconnaissance.

On the eve of departure, during preparations, we worked out in detail all the possible variations of the flight and the interaction between both experts in the crew and the crews themselves, and thoroughly tested and prepared the photographic equipment. As standard equipment the TU-95RTs had a perspective camera AFA-42/100 and two hand-held cameras AFA-39, one on the nose and another in the tail cabin.

To ensure secrecy, the decision was made of taking off at a 2-minute interval from the airfield at San Antonio, and proceed to the flight route in radio silence mode. After the first aircraft climbed, the leading aircraft would shoot a signal rocket from onboard, and the use of radio equipment was to be reduced to a minimum. This would enable the approach in secret to the search area, and prevent the withdrawal of the carrier from the group. The American naval commanders had in the past taken this course of action many times before, when they wanted to avoid identification and photographing of the carrier. In case of threat detection, sometimes the aircraft carrier sailed away from the main group, sometimes hiding under storm clouds. The last calculated position of the aircraft carrier at the time of departure turned out to be some 700 km to the east of Bermuda Islands. The flight time before the expected moment of detection was estimated to be about 5 hours.

The preparations for the take-off complete, now only remained some time for pre-flight rest.

The trip by bus through Havana at night was short. An hour later, we were at the airport and started the preflight preparations. Taking off at the exact preset time, and flying through all of Cuba from west to east, the tactical group took a course towards the area of the proposed encounter with the A/C “Saratoga.” The night sky in these latitudes is very starry, ideal for the study of Astronomy. To control our location I used a sextant and a pair of stars, thus defining it. Below, the Atlantic Ocean, its western part. Behind – the Bahamas, the islands in front of the Bermudas, which would take an additional three and a half hours to reach.

Radio communication between the two crews was not engaged, and the use of ELINT equipment was kept to a minimum. At the estimated distance, in the left sector, the onboard airborne radars were turned on to illuminate, thereby correcting the airplane’s flight path to the Bermudas Islands, clarifying its position on the map. Then we got to the target search area. All the restrictions on the onboard radio equipment were released, the onboard radar was switched on to its maximum range, 400 km. The real work began for all the specialists of the intelligence gathering complex.

I reported to the captain that to the detection perimeter of the USS Saratoga we still had some 600 km to fly. The commander gave the order to the SIGINT operator to start listening for radio broadcasts in the flight and guidance networks of the American naval aviation. There were no radio exchanges, reported the operator.

The ELINT operator was tasked with monitoring the work of the ship’s equipment which provided the American task group’s electronic jamming defense. According to his report, this type of defense was also not observed. The crew of the led aircraft confirmed this information.

Major N.G. Fedotov, the leader of the tactical group, decided to follow the same course, to be sure to reach the center of the assumed target area. When we were at a distance of 400 kms. from the target zone, the navigator-operator reported that there was a large mark on the position indicator radar. It was almost in the flight path of the aircraft.

Usually, many ships may be found in this area. Their evaluation may go from a giant tanker with oil coming to America, to a large container ship. These vessels have a fairly large displacement and can provide the same indications on the radar screen as an aircraft carrier. There’s only one solution: Fly an additional 200 km., then it will be clearly visible on the radar – it’s either one target, or many. And on the horizon the sun was coming out, shining directly in our eyes, as we flew towards dawn, on the east. Altitude: 7800-8100 m; beneath us, still dark; overcast at 3-4; the ocean calm. It was getting light right before your eyes.

Having reached 250 kilometers from the target, the SIGINT operator reported to the commander that naval aircraft were being sent from the aircraft carrier. Simultaneously, the ELINT operator confirmed the operation of the carrier’s anti-aircraft defenses. The call sign of the “USS Saratoga” left no doubt that the information from fleet headquarters was correct, and that we were in the right course. I quickly prepared an urgent radio transmission: “Arrived at the search area, according to ELINT equipment found the aircraft carrier “Saratoga,” place, altitude, remaining fuel, time.”

15 minutes later came up to us a pair of F-4 “Phantom” jet fighters. By their ID numbers and inscriptions it was evident that they were precisely from the A/C “Saratoga.” At an order from the commander, the radio operator transmitted a report of the interception by fighters to the CP in Cuba, to the CP of the Northern Fleet’s Naval Aviation, and to the Navy General Staff in Moscow.

The pair of Phantoms split, one went to the led aircraft, the other stayed with us. This one got closer, up to 15-20 meters, by the rear. The American pilots, using their portable cameras, took photographs of our aircraft. The SIGINT operator in the tail position took photos of the fighter jets with his AFA-39 camera, as a confirmation of the interception.

Then the SIGINT operator on the intercom informed the commander that the Americans had come quite close, about 10 meters, and that the second pilot (the RIO – tr.) got closer to the canopy and was showing a big photo of a naked woman. After that, he removed his oxygen mask and smiled broadly, pointing to the photograph, then to the West.

We knew that the American pilots in the air usually did not behave towards us too friendly, and now such extravagance… I told the SIGINT operator that that could not possible be. “It does,” -he replied- “Right now the Phantom is going forward, to your position.”

After undoing my safety belts and parachute straps, I leaned against the front windshield of the cockpit, and immediately saw very close to us the cockpit of a fighter, the broad smile of its pilot, and photos of women. The American pilot, after six months of combat patrol in the Mediterranean Sea, and just a day away from home, was just bursting with excessive emotion. Realizing his desire to communicate, I still showed him with a gesture that he should not approach any closer, and that he was better off going further away to the side. He was surprisingly understanding, removed the photo, and the fighter immediately went to the left at a safe distance from our plane.

At some 200 kms. from the target, from the radar screen it was obvious that there were no errors – that was a task force of a few ships. The only thing to do then was to perform the main task – to descend to low altitude and take a good shot of the A/C “Saratoga.”

At 180 kms from the target we began to descend, behind us, following us, after being ordered, the led aircraft also began to descend. The escorting Phantoms were nearby. Below it was already clear enough, the weather was excellent, and the onboard fuel was quite enough for a flight at low altitude.

We had already worked out the descent in pairs. The leader would descend to the desired low altitude, the led or wingman’s aircraft would take a safe altitude, higher than the leader, at no more than 300 meters, depending on cloud cover. I checked the onboard AFA-42/100 camera, the angle of inclination of the viewfinder already set at the desired inclination, so that the contrails from the running engines do not affect the quality of the photograph.

Near the target. The radar was already at a scale of 60, the target was clearly illuminated. We turned towards it. The lower edge of the cloud cover was at 1500 meters. From an altitude of 1200 meters and at a distance of 40 kms, the entire group could be examined visually.

We descended and remained at an altitude of 300 meters. The led crew, at 600 meters. The entire carrier group, consisting of the aircraft carrier and six escort ships, was following a western heading. Clearly visible from afar was the massive hull of the “Saratoga.” We began to maneuver so as to pass along its side no closer than 1.5 kilometers. At the same time, the accompanying Phantom started to maneuver near an open camera port on the left side of our aircraft, so that its fuselage covered the aircraft carrier, thus preventing any photograph. 15 minutes before he had been smiling at us widely, shortly after, maneuvering dangerously, trying to disrupt the completion of our task. We had our own task, he had his own…

We got closer to the aircraft carrier. On the deck superstructure the number 60 was clearly visible, but on the flight deck there were several aircraft, no more than 15 units, the rest seemed to be hidden beneath the deck. It was also clearly seen a helicopter flying close to the aircraft carrier, at an altitude of about 100 meters, following the same heading.

I pointed the camera’s viewfinder to the middle of the hull, and as soon as the nose of the aircraft carrier appeared, I pushed the shutter button. I heard the characteristic sound of the device’s functioning and saw the green light of the film advancer flash briefly. The photo shooting completed, I reported to the captain. But there was no certainty that the Phantom accompanying us did not ruin it. To get a duplicate image, we tried another run, but from the other side of the aircraft carrier.

We prepared and sent a radio transmission to the CP in Cuba: “Visually detected the A/C “Saratoga” № 60, heading 280 degrees, speed 15 knots, latitude, longitude, weather in the area, sea state, visibility, balance of fuel, time of detection. ”

After the duplicate run we turned to shoot the escort ships, but we approached them at a distance no closer than 1 km. From the tail position the SIGINT operator duplicated the whole shooting with the AFA-39 camera. At an order of the group leader, Major N.G. Fedotov, we exchanged flight altitude with the wingman. They started to overfly and photograph the ships, and we repeated the maneuver 300 meters above them.

While we were flying at low altitude, the accompanying Phantoms, having used up all their fuel, managed to refuel directly in the air from a tanker that rose from the deck of the aircraft carrier, and again came back to us.

After working in the area with the remaining available fuel, our crews went into a climb to flight level 9000-9300 meters, reported on the completion of work to the CP, then took a withdrawing heading from the area. The fighters escort accompanied us to about 200 kilometers from the aircraft carrier, and together went back and headed to their floating airfield.

Flying on a fixed route west of the island of Bermuda, we successfully completed this flight, landing at the San Antonio airfield. After landing, we reported to Colonel V.I. Dubinsky on the completion of this crucial task. He shook everyone’s hand and announced his gratitude, while adding that next day he’d call on us, while the navigator’s group would continue its work.

After landing, the Commander of the Soviet Navy, Admiral S.G. Gorshkov, gave orders to take the results of the aerial reconnaissance of the A/C “Saratoga,” and make a commemorative album for Fidel Castro.

Early in the morning we, together with V.V. Alexeyev, the navigator of Simachov’s crew, were taken to the CP of the anti aircraft defense of Cuba in Havana. Our films had already been processed and a large number of photos had been printed. Together with the specialists in photographic equipment from the technical support team of our flights, we decoded all the images, selected those of the highest quality, and started to design the commemorative album. We printed it in Russian and Spanish.

By evening it all was ready, it came out perfectly.

The next morning arrived at the villa the Commander of the Naval Aviation himself, Colonel-General Mironenko, looked at the album, and took it to a meeting between Admiral S.G. Gorshkov and Fidel Castro. After the meeting, he met once again with us, and said that while looking at the album very carefully, Fidel Castro said: “I know that in Cuba land Soviet planes and that they perform some of these tasks. But now, I personally see how like no one else they have direct contact with our potential enemy. These pilots should be proud of themselves.”

Mironenko also said that after the meeting with Fidel Castro, the Commander of the Navy, Admiral S.G. Gorshkov, gave him the command to present the crew commanders and the aircraft navigators with awards.

Exactly one year later, Major N.G. Fedotov was awarded the Order of the Red Banner, Major Simachov and I were awarded the Medal “For Military Service”, Capt. Alekseyev received a commendation from the Commander of the Soviet Navy. The other crew members received thanks from the Commander of the Naval Aviation.

overflies the “USS Saratoga” (CV-60)

Recollections of a Bear Intercept on December 19th, 1977

by CDR Dean Steele USN (ret.) – December 8th, 2010

I just read the report from Pavel Burmistrov (“A Photo for Fidel Castro”). I’ll give you some of my impressions about the report from our standpoint, together with more info on our launch and intercept. It is very interesting how perceptions can be radically different from the two sides

In December 1977 I was a lieutenant assigned to Fighter Squadron VF-31 flying the F-4 Phantom from the USS Saratoga (CV-60). We were just completing a six month Mediterranean deployment and were excited to be returning home before Christmas. As I recall, this deployment was being completed right on schedule without the undesired extension that occasionally happened.

The two F-4 squadrons onboard, VF-31 and VF-103, were primarily tasked with air to air missions including air defense of the task force. We were provided initial guidance information from ship radar controllers as well as the E-2C Hawkeye airborne platforms of Airborne Early Warning Squadron VAW-123. The Radar Intercept Officers (RIOs) in the back seat then acquired the incoming aircraft on radar and directed us to intercept, or in a hostile environment, gave us the missile firing parameters.

When there was a possibility that a Soviet aircraft would pay us a visit, we would be upgraded to a 5 minute alert status, which required us to be in the aircraft, on the catapult, and ready to go. When the launch command came we could then start the engines, complete final checks, and be ready to launch as soon as the ship had turned into the wind. Standing alert was boring (and sometimes cold and uncomfortable), but the possibility to launch and intercept an “enemy” aircraft that in wartime was capable of sinking our ship was exciting. We also enjoyed chatting with the squadron personnel and catapult crew who were also standing by for launch.

It was always expected that any potential Soviet attacker would be escorted when it reached possible ordnance release distance from the ship. This meant we needed to turn immediately and race out to intercept. After intercept we would escort the Soviet aircraft, take pictures for the intelligence folks and often attempt to get in any photo they took of the ship to show they had not arrived without being intercepted.

In this case as I recall, we intercepted at good range, flew formation on the tail (as usual), and waved to the Bear crew looking out of the observation windows, so we could communicate with them. We also compared the relative sizes of our government issued cameras with the friendly Soviet Bear crew in the tail. All in fun. The chance to see and, at least with hand signals, communicate with the Soviet crew was fun. No pilots I knew on our side had any real animosity toward the Bear crews. Yes, they were the potential enemy and all, but we realized we were just the “soldiers” on each side. Of course, in an actual combat situation we would have done anything possible to down the plane prior to missile launch.

As the Bear descended to fly past the ship it flew through a rather thick overcast. I flew as close to the tail as possible to preclude loosing visual contact, and was about to drop back to a safer radar trail when we broke out underneath the overcast.

Going past the ship I’m sure we did try to get between the Soviet airplane and the USS Saratoga, and might have flown a bit too close in order to “look good” while going by the ship, as well as an attempt to insert my plane into the photography, if possible. That would prove to Soviet Intel folks that we had escorted their planes. As for myself, my “maneuvering dangerously” at the time struck me that the Bear pilot was being extremely smooth, thus allowing me to more safely tuck in closer. The reason for getting close was to better see the crew. Due to the size of the Bear we could not get too close to the cockpit (I tried once but it was a bit scary). I didn’t consider it dangerous but maybe I was a bit cocky. We fighter drivers often prided ourselves in the ability to fly close, and in so doing I might have exceeded the parameters the Bear crew was used to seeing.

I do remember my back seater, Lt. jg. E. Holland, carrying a Playboy centerfold and pointing toward Cuba when showing it. It was also interesting to see the faces of the crew and have some interaction. That was the reason for the Playboy centerfold. I never considered the Playboy centerfold “extravagant”, but maybe his feelings could have better been translated as “in poor taste”, which I guess was true. Ha!

I can’t remember the details of the refueling but we often did that, and the speeds the Bear flew made it pretty simple to refuel while flying a loose formation. The refueling aircraft simply took over the escort while we “plugged”. After refueling was complete we would monitor the refueling drogue retraction and give the pilot a thumbs up, indicating that his plane looked good and the drogue had stowed correctly. We then signaled that we would resume flying lead and the tanker would depart.

After the Bears departed we were told to divert to NAS Bermuda since the ship was busy off loading ammunition. This process required the carrier to steer alongside the ammo ship while ordnance was passed via helicopter and cable. This allowed the carrier to get rid of its ammunition before entering port and for it to then be readily available to pass to another ship or be taken back to a port where it could be appropriately stored. I distinctly remember us (naively) hoping we would receive orders to fly directly home to NAS Oceana, VA, where our wives awaited, but sadly that did not happen. A few hours later we flew back and landed on the big gray boat instead.

Pavel Burmistrov in his report indicated a belief that carriers would often sail away from the task force to avoid being detected by incoming Soviet aircraft. I was not privy to those decisions about the larger tactical picture but seriously doubt that. I never heard of a carrier departing the rest of the battle group to hide. I strongly suspect we maintained a defensive posture a lot like we would during an actual Soviet attack in a combat situation. If weather presented itself, a carrier might have occasionally ducked into a rain shower to avoid visual detection, but I believe the major effort was to exercise all defensive measures of the task force as an exercise. Remember, a carrier skipper also had to think about landing airborne planes before their fuel ran out. For this reason, and the safety of the deck crew, I doubt they would drive the ship into any serious weather.

Author: Miguel Vargas – Caba

From Miguel Vargas – Caba for War History Online

All Photos Provided by the Author

A Short Glossary of Soviet Military Organization and Terminology

AFA – Aviatsionnyy Fotograficheskiy Apparat – Aviation Photographic Apparatus/Air photocamera.

CP – Command Post – The reconnaissance airplanes of the SNA usually reported their findings to their home base, in this case the airbase at San Antonio, near Havana, Cuba, to the SNA’s Headquarters in Leningrad, USSR, and to the Soviet Navy’s Headquarters in Moscow.

Lead/Led aircraft – A system in use by the Soviet Naval Aviation whereby a Bear rarely flew alone, especially when flying outside the USSR. Two airplanes were the norm with the “Lead” or “Leader” navigating the flight routes, while the “Led” or “Wingman”, followed the “Lead” close behind.

ODRAP – Otdyel’nyy Dal’nyy Razvedyvatel’nyy Aviatsionny Polk [lndependent Long-Range Reconnaissance Air Regiment] – A division of the Soviet Naval Aviation. The Tupolev TU·95RTs Bear D aircraft usually belonged to these regiments, in all the fleets of the SNA.

OPLAP – Otdyel’nyy Protivo-Lodochnyy Aviatsionny Polk [Independent Antisubmarine Air Regiment] – A division of the SNA. The Tupolev Tu·142 (Bear F) was usually assigned to these regiments.

Olen’ya – (also known as Olenyegorsk) – Primary airfield of the Soviet Naval Aviation in the Kola Peninsula, 92 km south of Murmansk, and from where TU·95RTs took off after refueling on their long flights to the Central Atlantic Ocean, Cuba, Guinea, and Angola.

Pilot 1st Class – Soviet pilots, both in the Air Force and in the Naval Aviation, were ranked according to a particular system – different from that used in the West – whereby the pilots started as Pilot 4th Class and progressed towards the 1st Class level, regardless of their rank. This system was based on experience and length of service rather than rank.

RTs – Razvedyvatel’nyy Tselekazannyy [Reconnaissance Target Indicator] – The type of mission function this particular version of the Bear was tasked with while on operational flights.

SNA – Soviet Naval Aviation – Sometimes, even in Western writings, it is known by its Russian acronym AV-MF, which stands for Aviatsiya Voyenno-Morskogo Flota, or literally: “Aviation of the Military Seagoing Fleet.”