Desperate times sometimes call for desperate action. It was through just such an event that, in February 1943, American troops avoided disaster outside the Tunisian town of Sbeitla.

The Valentine’s Day Offensive

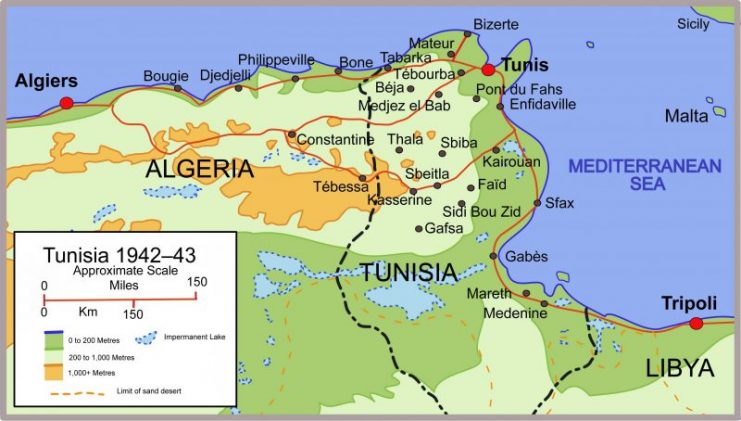

By early February 1943, the Allies had Axis forces in North Africa contained in an ever-shrinking patch of ground around the ports of Tunis and Bizerte. Though the push to take these ports had run into difficulties, the Allies retained the upper hand.

Then, on the 14th of February, the Germans launched a counter-attack. In the area around Sidi Bou Zid, the Germans hammered American forces.

By late afternoon on the 15th, it was clear that the Americans could not hold the ground they occupied around Sidi Bou Zid. Instead, they needed to pull back to the Western Dorsal mountain chain. At 5 pm, General Eisenhower, supreme commander of the American force, gave the commander of the First Army, General Anderson, permission to retreat.

Why Sbeitla?

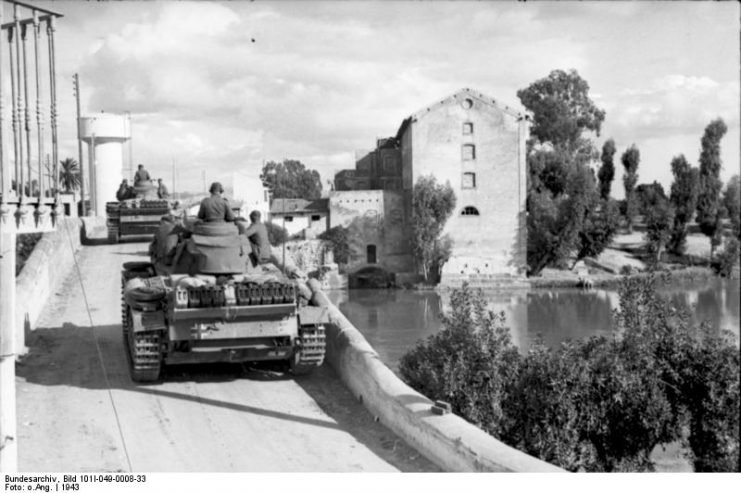

Sbeitla was an ancient city in a strong defensive position behind a deep river channel. It was also the last substantial position before the passes through the Western Dorsal.

To manage an orderly retreat, the Americans needed to hold their ground around Sbeitla for as long as possible, to buy time for troops to get through the mountains.

If the Germans got through before the army had time to regroup, then they could attack the important supply base at Tébessa and cut off the supply lines of British forces facing Tunis and Bizerte.

Panic

Unfortunately, the American troops were in a state of disarray. The sudden onset of the German attack caused widespread panic and shattered previously orderly units. Men and vehicles streamed back towards the passes.

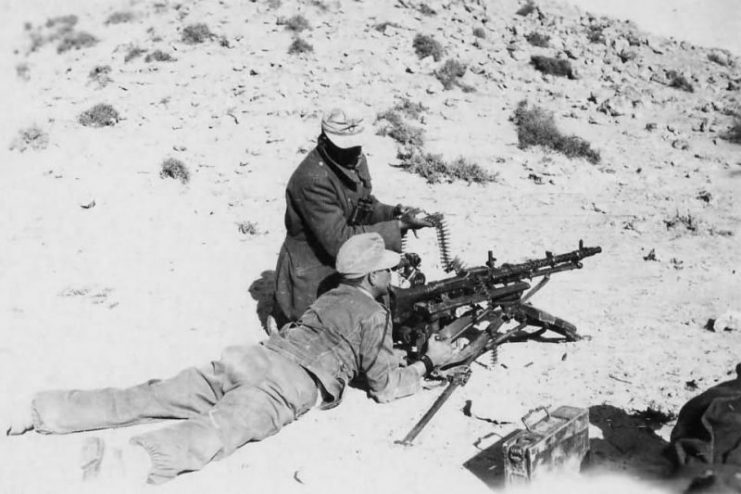

During the night, German “reconnaissance by fire” – a tactic of shelling positions in which the enemy might be concealed – added to the chaos. If they fired back, then this would reveal their positions and allow the Germans to target them.

The sudden appearance of shelling on previously quiet areas, the very essence of reconnaissance by fire, caused panic as men found themselves unexpectedly under attack in the darkness.

The roads became clogged with fleeing men and vehicles, as well as the burning wrecks of tanks and transports the Germans had hit.

Moore and Hightower

Not everybody succumbed to panic, even in these desperate circumstances. On the 15th, First Lieutenant Robert Moore, an executive officer, found himself isolated from his unit, with only his command tank, a wrecking crew, and a kitchen crew. He set out to see what he could do to help.

Moore found Lieutenant Colonel Louis Hightower, the commander of a destroyed battalion, and a few other survivors. This ragtag group organized a rearguard action east of Sbeitla, to hold up the Germans on their way to the town.

Robinett Takes Position

Meanwhile, General Paul Robinett had been sent in with a force of soldiers and tanks. His role was to carry out the rearguard action needed to cover the retreat.

Robinett and his men took up positions southeast of Sbeitla, astride the main road into the town. Hightower, with the units he had pulled together from the ruined American formations, took a position north of Robinett.

Throughout the night of the 16th, Robinett’s men prepared their positions. Tank destroyers formed the first line, a series of outposts ahead of the main force. Behind them, tanks were concealed in valleys and depressions. Behind that lay the artillery.

While they were digging in, engineers blew the American ammunition dump at Sbeitla, to keep it out of enemy hands. The sound convinced some men that the Germans were shelling the city, intensifying the panic of the retreat.

The 17th

On the morning of the 17th, the Germans attacked Robinett’s line in force.

Three waves of tanks hit the American tank destroyers, who fought them for half an hour before retreating. Under heavy enemy fire, many kept moving into Sbeitla rather than join the main line, and so were lost in the chaos of retreat.

The German attack was ill-timed for the Americans. Their artillery was just being repositioned and so was not ready for combat. It provided far less support than Robinett had hoped for.

Within an hour of first reaching the Americans, the Germans hit their main line.

Gardiner

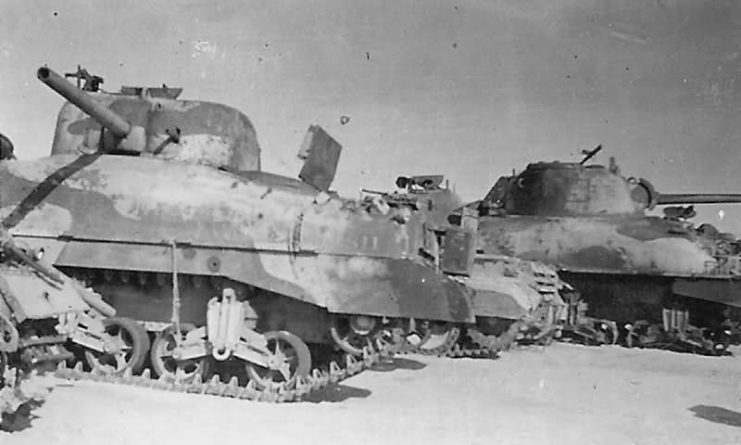

One of the first formations they met was a tank battalion led by Lieutenant Colonel Henry E. Gardiner. Gardiner had hidden his Sherman tanks well despite their high turrets and so the Germans drove straight into a trap.

Around noon, Gardiner saw 35 enemy tanks approaching. He held fire until they got close, then had his battalion open up in a volley that stunned the Germans. Fifteen of their tanks were damaged or destroyed and the rest backed off without hitting a single one of Gardiner’s tanks.

While the Germans regrouped, the American artillery at last got into position. They bombarded the enemy tank formation, further weakening it.

At quarter past two in the afternoon, the Germans attacked Gardiner’s south flank and the fighting began in earnest.

Around this time, the order reached Robinett to withdraw. Gardiner, his battalion in trouble, asked to pull back but was told to hold his ground to cover the withdrawal of an infantry unit. At last, he withdrew under heavy fire. Many of his unit’s tanks, including his own, were destroyed, and he escaped on foot, evading enemy tanks by distances of a few feet.

Robinett attributed much of his success at Sbeitla to Gardiner and his men.

Aftermath

Around half past five, Robinett managed to break contact with the Germans. His troops withdrew through the pass and joined the other Americans preparing to hold the Dorsal.

In the rush to retreat they had to abandon supplies, ammunition, and even aircraft. They were, however, saved from far greater disaster by the courageous defense of Sbeitla.