Sea mines are some of the most terrifying and destructive weapons at a navy’s disposal. Capable of wreaking havoc on fleets, they’re a staple of war that can trace their origins to Imperial China. They’ve undergone changes over the centuries, becoming the simple, yet complex explosives they are today.

What is a Sea mine?

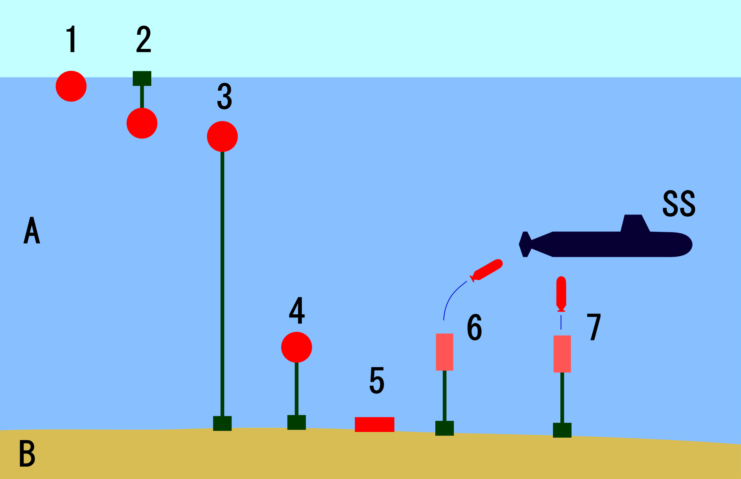

A sea mine is an underwater explosive device designed to detonate in the presence of vessels. There are three main types. Bottom mines rest on the seafloor in shallow water. Moored mines float above the seafloor, are attached to a weight, and are used against submarines and ships. Drift mines float freely on the surface of the water and, as such, are rarely used.

There are three ways mines are laid. The first is via aircraft, the preferred method for offensive operations, as it provides rapid minefield replenishment with little risk. Similarly, mines laid by submarines are used offensively, but saved for covert missions.

The most economical option is surface laying, as ships can transport the most amount of mines. There are many complications with this method, as the navy carrying the mines has to take into account the risks associated with possibly not having control of the waters. As such, they’re typically reserved for defensive measures.

There are countermeasures to combat the use of sea mines. Known as “minesweeping,” it involves a number of tactics, including the use of unmanned systems, advanced weaponry and sonar technology. Two ships can neutralize a minefield by dragging a cable designed to cut mooring cables, after which the mines are detonated by gunfire. As well, bottom mines can be set off by “tricking” the explosives into thinking a ship is in the vicinity.

Sea mine precursors and the American Revolution

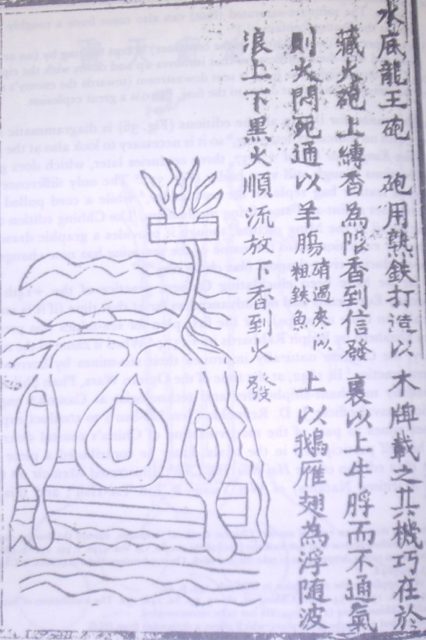

The earliest precursors to sea mines trace back to Imperial China, where they were used against Japanese pirates. In the west, the first examples date back to the reign of Queen Elizabeth I of England, and later to Dutch inventor Cornelis Drebbel, who was tasked by King Charles I of England to come up with new weapons, including the failed “floating petard”.

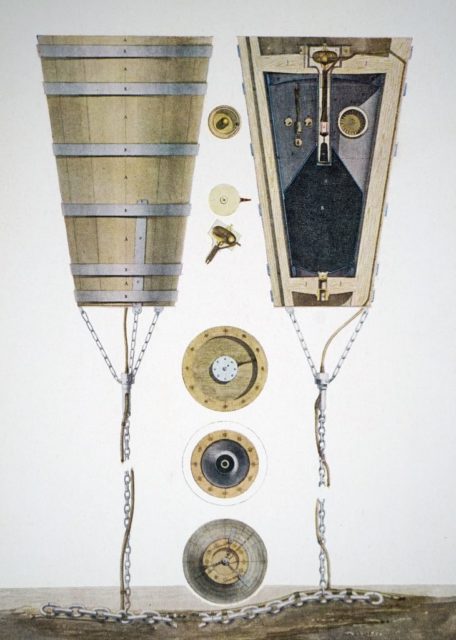

The invention of the sea mine is directly attributed to David Bushnell, a Yale student who discovered gunpowder could explode underwater. In 1777, during the American Revolutionary War, General George Washington granted him permission to sink a fleet of British ships in the Delaware River.

Bushnell’s mine consisted of gunpowder in a key, supported by a float on the water’s surface. Within the device was a gunlock rig, meaning the slightest impact would cause an explosion. It took out a small frigate, HMS Cerberus, killing four.

Global use during the 19th century

While US use was of sea mines was scarce during the 19th century, given John Quincy Adams’ belief that their use was “not fair and honest warfare,” they were prominent in Europe, particularly in the Imperial Russian Navy.

In 1812, Russian engineer Pavel Shilling exploded a sea mine using an electrical circuit, and in 1853 the Jacobi mine was invented. Tied to the seafloor by an anchor, it used a cable connected to a galvanic cell powered from shore. The production of the mine was approved by the Committee for Mines and eventually phased out its competitor, the Nobel mine.

The Imperial Russian Navy also used sea mines during the Russo-Turkish and Crimean wars, the latter of which saw the laying of over 1,500 mines in the Gulf of Finland.

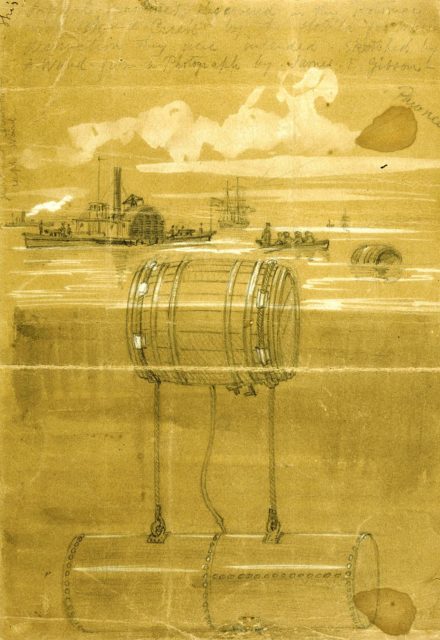

During the American Civil War, the Confederate Navy used sea mines against the Union naval force, sinking the USS Cairo in the Yazoo River and 27 Federal vessels during the Battle of Mobile Bay in 1964.

After 1865, the US chose the sea mine as its primary weapon for coastal defense. Initially controlled by the US Army Corps of Engineers, it was later the responsibility of the Artillery Corps, before being given to the Coast Artillery Corps in 1907.

Development during WWI and WWII

Following the conclusion of the Russo-Japanese War, there was an attempt to have sea mines banned as weapons of war at the 1907 Hague Peace Conference. This didn’t happen. However, it was decided drifting mines would be outlawed, due to their uncontrollable nature.

Throughout the course of World War I, sea mines were used as a defensive measure against German U-boats. An example of this was the North Sea Barrage, which the Allies began laying in 1918. It spanned 250 miles from Scotland to Norway, and consisted of 72,000 mines, taking out six submarines and damaging numerous German vessels.

The Germans fought back with their own mines, sinking British merchant and naval vessels. One of the German Navy’s most successful mining campaigns was the sinking of the HMHS Britannic by SM U-73.

World War II saw sea mines become an offensive, rather than defensive, weapon. German U-boats patrolling the Atlantic used them to mine British ports and routes, and the overall design of the explosives changed. While before they only detonated upon contact, they could now explode based on acoustic, magnetic and pressure changes in the water – they were even programmed to only detonate against certain ships.

One of the largest strategic uses of sea mines was Operation Starvation, in which the US Navy laid 12,000 mines along Japanese shipping routes in the Pacific. This not only sank 650 Japanese ships, it showed how they could be used for psychological warfare, as nearly all ships were made to stay in port or divert course.

Sea mines in the post-WWII era

Following the end of WWII, sea mines largely fell out of use, as the majority of countries were scaling back their militaries. This was especially true of the US, as its military believed they would not be a part of advanced warfare. However, it found that its disregard for the explosives greatly affected their abilities during the Korean War.

The Korean Navy held up the US fleet for almost a week, despite having only 45 vessels, because it laid 3,000 mines in the waters off North Korea. As well, 70 percent of the US Navy’s losses in Korea were the result of mine warfare, made worse by the fact that only two percent of sailors were trained in minesweeping. This prompted US Chief of Naval Operations Admiral Forrest Sherman to change the service’s stance.

The US developed the Destructor-class of mines in 1967, and while highly-sophisticated, they were rarely used in Vietnam. The Quickstrike Mine was favored by US military forces, as it was relatively cheap, developed for strategic use and could be used defensively.

Sea mines continued to be used in conflicts between the Vietnam and Gulf wars. Once the Gulf War began, they became the explosive of choice for the Iraqi Navy, inflicting severe damage on the USS Tripoli (LPH-10) and USS Princeton (CG-59). Upon the war’s conclusion, eight countries conducted clearance operations in the Persian Gulf.

The use of sea mines today

Given the destructiveness of sea mines, international law now requires that all signatory countries declare areas in which they’ve been placed. However, this is not a full-proof system, as the exact locations are not revealed. As well, some countries refuse to comply with the law and therefore do not disclose such information.

Today, the US uses two different types of mines. The first is the aforementioned Quickstrike Mine, designed for use against subsurface and surface craft. They’re placed in shallow waters by aircraft. The second is the Submarine-Launched Mobile Mine (SLMM). As the name suggests, it’s deployed by submarines and typically used in areas where other mine-laying techniques aren’t an option. Each SLMM is equipped with an MK37 torpedo that has a mine target detection device.