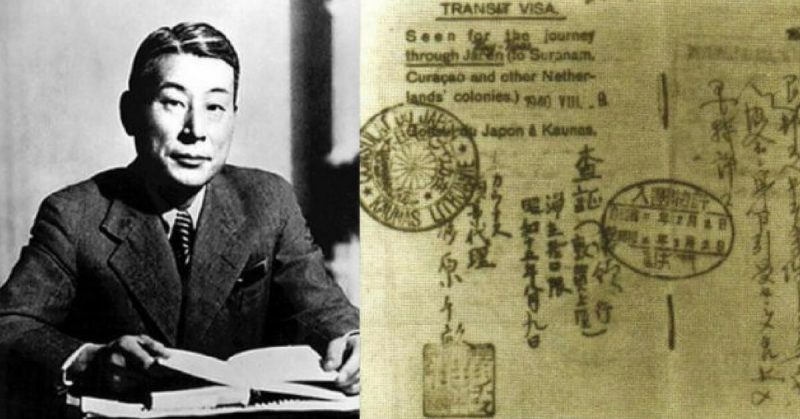

Chiune Sugihara, better known as Sempo, was a Japanese diplomat who came to prominence during WWII. Sugihara was responsible for saving the lives of thousands of European Jews by providing them with the necessary papers for which they could emigrate to Japan.

The Japanese never officially adopted the anti-Semitic doctrines of the Third Reich. The Germans did try to influence their Japanese allies to conduct extermination policies, but the closest they got was forming a ghetto in Shanghai. The rules that led to the Holocaust did not apply in Japan, which enabled Sempo Sugihara to fulfill his compassionate duty after witnessing the extermination of Jews in Europe.

Born into an upper-middle-class family, Sugihara’s father intended that he become a physician, but instead, he purposely failed his admission test and went to study English in Tokyo. Then he applied for the Foreign Ministry in 1919 and was accepted.

Sugihara’s first assignment was in Harbin, China, where he took part in negotiations with the Soviet Union concerning the Northern Manchurian Railroad. There was a dispute between the USSR, Japan, and China over the ownership of that particular part of the railroad.

During his stay in Harbin, Sugihara learned Russian and German and became an expert on Russian affairs. He was a promising diplomat, but his concern over the mistreatment of Chinese civilians by the Japanese authorities got him branded as a disobedient servant of the Empire.

He was a skilled diplomat, and his competence was needed in Europe. In 1939 Sugihara was transferred to Kaunas, Lithuania, where he served as a vice-consul of the Japanese Consulate.

He was instructed to monitor Soviet-German relations and report to his superiors in Berlin and Tokyo. He was also in contact with elements of the Polish intelligence. As the invasion of Poland began, Polish Jews fled to Lithuania. The following year the Soviets invaded the Baltic states, including Lithuania.

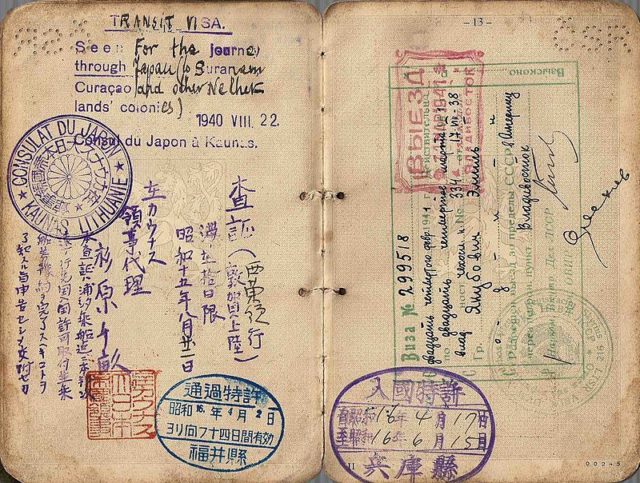

Local Jews and those seeking refuge were now applying for exit visas in large numbers. An exit visa was of great importance, as no sovereign country would accept an immigrant without one. The Dutch government made an exception. They approved access with no exit visa to its colonies in Curacao in the Carribean and Suriname in South America, but the number of people was limited. Thousands of people queued at foreign consulates, desperately seeking permits.

Several hundred people applied for a visa at the Japanese consulate, but the Japanese government had very strict criteria concerning its immigration policy. A permit was only given to individuals who had gone through appropriate immigration procedures and had enough funds. Given the circumstances, many failed to reach that criterion.

Sugihara asked for instructions from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, but their answer was uncompromising. They were prepared to issue visas for Japan only as a transit option to a third country.

The vice-consul then acted on his own. He was well aware that the Germans and Soviets (who were still operating under the non-aggression pact of 1938) had their own agendas and that the war was coming to Lithuania soon enough

From July 18 to September 4, 1940, Sugihara ignored all orders from the Ministry and granted visas to as many applicants as he could. He arranged meetings with Soviet officials and negotiated with them that the refugees could travel via the Trans-Siberian Railway. Using the opportunity, the Soviets raised the price of the journey to five-times the regular ticket price.

Sugihara, who was called Sempo by the applicants became well known among the Jews in Lithuania. He was seen as a beacon of hope and a man whose principles were not overridden by the crushing pressure of bureaucracy. He wrote day and night, issuing a month’s worth of visas during a single day!

When the consulate in Kaunas was closed, and he was ordered to evacuate, he issued visas on the way to the railway station. When there was no time left, he stamped and signed blank pages and distributed them so that they could be forged into exit visas.

It was reported he was so concerned about the fate of those people that he bowed deeply just before his departure and said: “Please forgive me. I cannot write anymore. I wish you the best.” The answer came from the crowd by an unknown man who spoke for all of them when he said: “Sugihara. We’ll never forget you. I’ll surely see you again!”

While the train was leaving the station, he threw more documents out of the window into a crowd of desperate refugees.

As he departed reality struck, and he wondered what his superiors would say. Luckily, in the confusion caused by the hasty closure of the consulate, Sugihara avoided detection. His superiors failed to find out how many exit visas were issued by him.

It is hard to determine how many managed to flee from Lithuania thanks to Sugihara, but research estimates he issued around 6,000 visas. As some of them were group permits enabling entire families to travel, the number of people he helped is suggested to be around 10,000. Unfortunately, not all managed to escape, as the German invasion of the Soviet Union came less than a year later.

Sugihara spent the rest of the war serving in consulates in Prague and Bucharest before the Soviet troops arrested him after the capitulation of Romania in 1944. He returned to Japan in 1946, after spending two years as a POW, together with his wife and three sons.

In 1985 his actions were acknowledged by the government of Israel, and he was granted the title the Righteous Among the Nations, reserved for individuals who helped Jews during the Holocaust. When asked about his motives for helping all those people, Chiune Sempo Sugihara humbly answered:

“I do it just because I have pity on the people. They want to get out, so I let them have the visas.”

His philanthropy went largely unnoticed in Japan during his lifetime. However, he was posthumously awarded some honors, including streets named after him, and an asteroid that bears the designation 25893 Sugihara.