The summer of 1942 should have been a joyous period and full of prospects for Charles “C.B.” Smith, who had recently graduated from high school. Yet it became a time of apprehension as the United States was embroiled in World War II, highlighted by the recent Battle of the Coral Sea that resulted in a strategic Allied victory that left both the U.S. and Japanese with major losses to their naval fleets.

Weeks after this battle, while conflict brewed in both the South Pacific and Europe, Smith was working at a small shop in St. Louis repairing electric motors when he not only registered for the draft, but also made the decision to enlist.

“I volunteered for both the Army and Navy but neither one of them wanted me because I had some medical problems with my ears,” said Smith. “After that, I just thought that I was considered ‘4F.’” That was a classification given to military applicants deemed unfit for service due to medical or dental issues.

With the opinion his services were not needed, Smith packed up some clothes and traveled to California in early 1943, where he found work in a synthetic rubber plant south of Los Angeles. He explained that he was doing “pretty good” in his civilian endeavors when he received a letter stating he needed to report to Jefferson Barracks in St. Louis.

“I took my draft induction physical in St. Louis and told them that I would be interested in the Navy,” Smith recalled. “They sent 12 of us over to the federal building and interviewed us. Then,” he concluded, “they said they had openings in the regular Navy, Coast Guard and the Seabees.”

When Smith asked about the mission of the Seabees, he was informed they were construction battalions that built naval bases, airstrips and provided maintenance support in several combat theaters of the war. With an electrical background from construction work he did for a contractor in Russellville during high school, he was convinced the Seabees was the service for him.

“I was inducted into the Navy on April 2, 1943 and they sent me to the Seabees boot camp at Camp Peary, Virginia,” he recalled. “That lasted about six weeks or so and then we came home for 9 days of leave before returning to advanced training at Camp Peary,” he added.

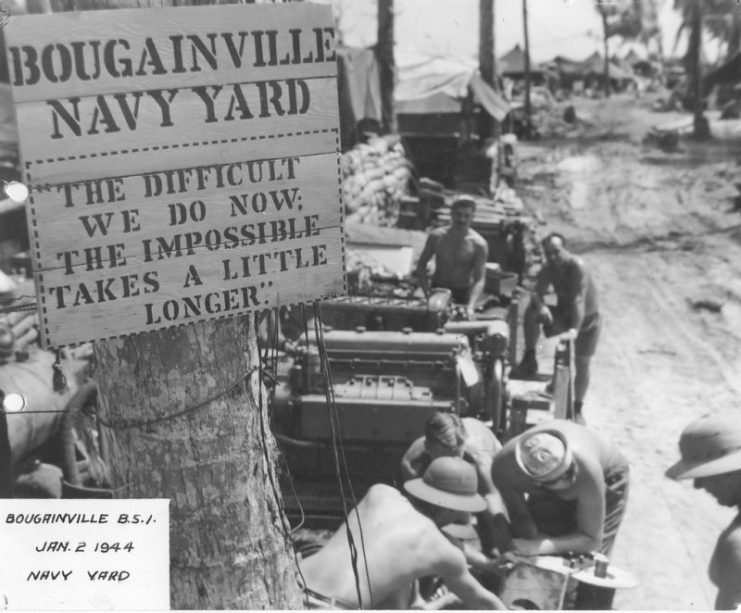

Assigned to Naval Construction Battalion Detachment 1007—a newly commissioned heavy equipment repair outfit—he was transferred to Port Hueneme, California, in mid-June 1943, for additional training. Three weeks later, he and the battalion boarded a troop ship for a journey of more than three weeks to their new home in the South Pacific.

“We got off the ship at the island of Espiritu Santo,” Smith said. “It was a small island 900 miles or so northeast of Australia and was a military supply base during the war.”

Smith went on to explain, “When we got there, they had a place for us already fixed up with Quonset huts to stay in.” Grinning, he added, “There were 250 of us in the outfit but only 20 or so of us were 18-21 years old. The average age of those in our group was 37 years because they were all experienced in their specified jobs.”

Despite his appointment as an electrician, Smith noted the first eight months of his overseas combat assignment was less than glorious since it was spent on KP (kitchen police) duty, primarily helping dispose of the trash produced by the cooks in the mess facility.

In his off-duty hours, Smith went to a nearby airstrip where B-17 Flying Fortresses and B-24 Liberators were repaired, and hitched rides when test flights were conducted. Other times, he and friends visited an inert volcano that had become filled with water and served as a “swimming hole.”

As the months progressed, he was sent to work in the electrical shop but eventually became responsible for the telephone exchange system for the battalion when the sailor who previously held the position transferred back to the States.

“We were situated in a coconut grove and that’s where I learned how to climb coconut trees,” he said. “Our communication wires had to be strung across the trees and other times the trees had to be scaled to trim fronds and remove coconuts to prevent them from falling on our huts.”

Activity slowed on the island as the war progressed to different locations and the bomber strip was closed. During this period, Smith learned to operate various types of construction equipment and machinery staged in a centralized location after it was repaired by his fellow Seabees.

In August 1945, two years after their arrival, the battalion boarded a troop ship for the United States. Upon their return, Smith was briefly assigned to Quonset Point, Rhode Island. Weeks later, he served aboard a ship that sailed to Honolulu and back to San Diego carrying a group of Marines. On February 2, 1946, he received his discharge from the U.S. Navy.

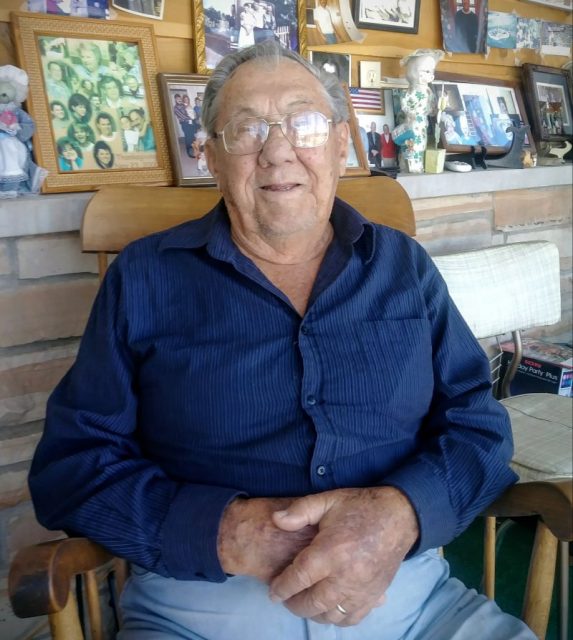

In the years after the war, Smith married, raised eight children and enjoyed a lengthy career as a lineman with Missouri Power and Light. His time in the South Pacific, he mirthfully recalled, may not have been as inspiring as that of other combat veterans, but was a period of great influence in his life.

“I volunteered three times before they drafted me but they got me when they needed me, I guess,” Smith said. “It was our war…our responsibility, and I enjoyed my time in the service even though it wasn’t in combat.”

He added, “And I must say, it was an experience that helped me through a lot of things because I learned to climb coconut trees during the war, which,” he grinned, “may not seem like much but it sure helped me when I became a lineman for the power company years later.”

Jeremy P. Ämick writes on behalf of the Silver Star Families of America.