Close your eyes and imagine an act of wartime courage. What do you picture? A soldier carrying a comrade to safety? A captain buying his crew vital time to abandon ship? A pilot hurtling through the skies, intercepting the enemy’s deadly engines of war?

Imagining acts by military personnel is natural but civilians were also the heroes of some of the most extraordinary acts of wartime courage. One of those acts took place in Soham, England in June 1944.

Moving Supplies

The Second World War was an industrial war. More than in any war before or since it was fought with the provision of entire economies. In Britain, factories worked around the clock to make vehicles, weapons, and ammunition. Supplies from America poured through the ports on a daily basis.

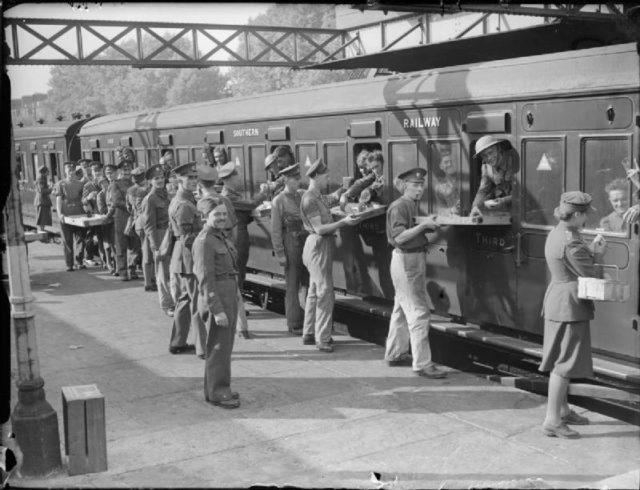

To move all those goods around, the railway system worked far beyond its previous maximum capacity. A 50% increase in military freight was managed by 1943 without increasing the number of wagons, through the initiative and efficiency of the railways’ controllers.

In late May 1944, D-Day was approaching. Troops and supplies were being transported to the south coast for the invasion while other areas of the war still had to be maintained. Any failure in the system could have enormous consequences.

A Deadly Cargo

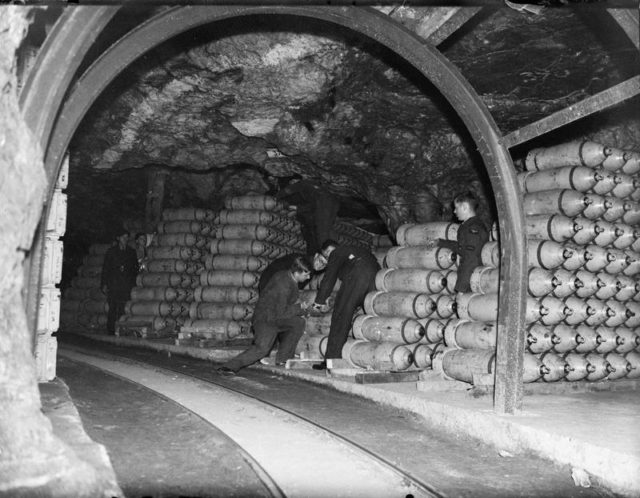

On May 31, 1944, a 61-wagon train was filled with bombs at the port of Immingham in the Humber Estuary. The weapons were intended for a USAAF bomber group in Colchester. The train had been reduced by ten carriages but was nearly 400 meters long.

Thousands of bombs meant a potentially deadly cargo. Great care was taken in transporting them. The explosives were sent separately from the primers and detonators. Low-combustibility tarpaulins covered the loads to stop sparks from the coal-fired engine. The train traveled slowly and was checked at every stop.

Ordinary Men in a Dangerous Job

There was three staff on the train. Ben Gimbert, 41 years, was an experienced engine driver. He was at the controls. Accompanying him up front was his fireman, Jim Nightall, 22 years. At the back of the train was Herbert Clarke, the guard. He was 59 years old, a veteran of the railways.

Just after midnight on June 2, the train set out from a small town in Cambridgeshire headed toward Soham. In the signal-box at that station, sat – Frank “Sailor” Bridges.

They were ordinary men doing ordinary jobs, made extraordinary by their cargo and the courage they would soon have to show.

Fire!

As they approached Soham, Gimbert looked back along the train. What he saw was terrifying. Flames were coming from the bottom of the first bomb carriage.

Acts of Courage

Gimbert thought quickly. He could not let himself panic. Stopping the train suddenly might trigger an explosion igniting its whole cargo of thousands of bombs. The train, its crew, and much of the town would be wiped out.

Something had to be done. If the fire ignited any of the bombs in that first wagon, they would trigger the rest of the cargo, with the same disastrous results.

He brought the train calmly to a stop and instructed his fireman to uncouple the front wagon. Nightall grabbed the coal hammer in case the coupling was hot, leaped from the train, and rushed to detach the rest of the carriages from the burning one. Gimbert joined him, as did Bridges and Clarke, rushing from the signal tower and the back of the train to help.

Gimbert and Nightall then got back in the engine and headed along the tracks, dragging the flaming cargo behind them, leaving the rest safely out of range.

Gimbert was intent on getting the train clear and saving the lives of others before he took care of himself. He was still at the engine’s controls when, barely out of the station, 400 tons of bombs exploded in the wagon behind him.

A Swift Response

Gimbert was thrown clear of the train. Battered, dazed, and in incredible pain, he survived the explosion. Nightall and Bridges were not so lucky and were killed in the blast.

The explosion threw Clarke 80 feet. Staggering to his feet, he realized that if the mail train hit the remaining carriages, it could still cause the devastating explosion they had just avoided. In the aftermath of an explosion that had almost killed him, he made his way two miles back up the line, laying warnings for oncoming trains.

The explosion carved a crater in Soham 15 feet deep and 60 feet wide. Hundreds of homes were damaged, thirteen beyond repair. Many people were injured, but no-one in the town was killed.

Emergency services rushed to help from across the surrounding area. With only days before D-Day, this was a vital rail line. Civilian and military engineers hurried to the scene. Within eighteen hours, both rail lines through Soham, wrecked by the explosion, were back in working order.

What Was Lost, What Was Saved

Two brave men lost their lives, and two others were injured protecting Soham from a devastating explosion. Without their courage, countless others would have been killed or wounded, and a critical transport route would have been crippled.

Gimbert and Nightall were both awarded the George Cross for their courage during the accident, Nightall posthumously.

In war, many heroes carry weapons, but some civilians are heroes by putting others before them when duty calls.

Source:

Gordon Brown (2008), Wartime Courage.