Following the D-Day landings of June 1944, the Allies poured troops into Normandy. By the 25th of July, they had 1,450,000 soldiers ashore in France, ready to liberate Europe from the power of Nazi Germany.

Not all of these troops were on the front lines. Some were held in reserve or resting between battles. Even had the generals wanted to send every man in, they were contained by the Germans, narrowing the front line and preventing all these troops from being used.

Hundreds of thousands of soldiers found themselves living a strange, dislocated life behind the front lines.

Surroundings

The soldiers lived amid a mixture of abject destruction and smooth efficiency.

The D-Day beachhead had seen some of the most intense fighting in history, both on the first day and in the weeks that followed. The landscape was littered with the shattered remains of concrete bunkers and the burnt-out wreckage of tanks.

Villages had been reduced to bullet-riddled ruins as the occupiers tried to fight off the invaders. The ground was cratered by the impacts of bombers and artillery. Fields were torn up by countless track marks.

Amid this destruction, military administrators carried out remarkable feats of logistics. Heaps of food, fuel, and ammunition sat beside rows of newly arrived tanks, waiting to be distributed to their units. Telephone wires lay strung across the trees while signposts directed men around this zone of bustling activity.

Local Relations

Reactions from the locals were mixed. Though some were relieved to be liberated, many were indifferent to which band of armed foreigners was clogging their roads and ordering them around.

The inhabitants of the region had been through a grueling ordeal. First occupation by the Germans, then the heavy bombing that preceded the invasion, and then the fighting between the Allies and the Nazis. They had lost friends and relatives, then had their lives turned upside down as their homes and businesses were damaged or destroyed. Preoccupied with rebuilding, they didn’t always pause to give the soldiers the praise they wanted.

Some locals tried to make up for their losses by looting dead bodies. This could end badly, and some were shot by military police.

A few soldiers got lucky and found a warm welcome as families provided hospitality to the liberators, offering them home-cooked meals. The region’s prostitutes also welcomed them with open arms, leaving medical officers to deal with the consequences.

Staying Entertained

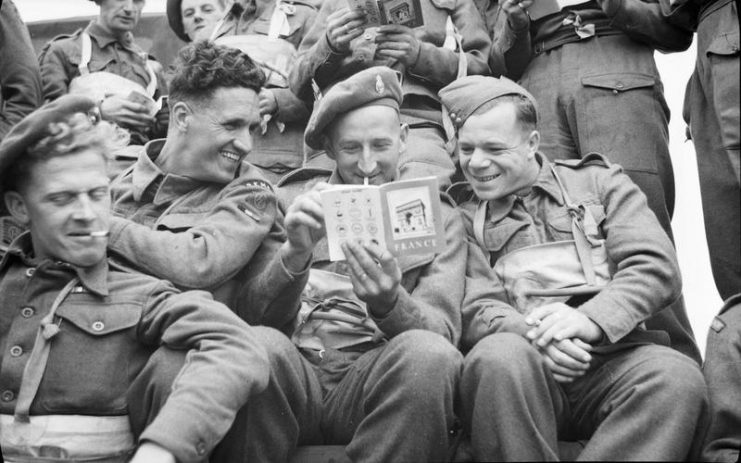

Options for entertainment were limited. When they weren’t at the fighting front, soldiers did whatever they could to avoid boredom. Walks through the less ravaged parts of the Norman countryside. Reading books or comics if they had them. Playing cards. Drinking the locally brewed cider and calvados.

Communication provided a lot of the entertainment. Some of the time, this meant writing letters back home, reassuring families that they were still alive and telling them a little about their adventures. But mostly it came down to soldiers chatting with each other about whatever came to mind. This was often the things they missed from back home, particularly women, though the war itself inevitably played a part.

Chaplains sometimes tried to encourage more enlightened conversation. Padre Lovegrove of the Green Howards, a British regiment, tried to keep his men connected to their civilian lives by talking about their homes and jobs, to retain some sense that normality was waiting for them.

Ironically, it was often harder to stay connected to events just down the road. Army newsletters sometimes provided updates on the war, but these couldn’t always be produced in the field. The men were otherwise reliant on gossip to keep them informed, so often they had little idea of what was happening while they rested.

Staying Supplied

Shortage of supplies is often the bane of the poor soldier, and the British Army’s history was full of incidents when the poor infantry had been left cold and hungry. But despite the expectations of many soldiers, supplies were plentiful in Normandy.

After years of rationing back home, this was a source of great pleasure for the British troops. They were regularly provided with more plentiful food than they got in Britain. This was supplemented by whatever they could find, buy, or steal from the locals, depending upon their morals and opportunities.

British supplies were nothing compared with those of the Americans, whose substantial rations left the British green with envy. Cartons of C and K rations provided the Americans with regular, nutritious, though sometimes monotonous meals.

Like the British, they bolstered these with locally acquired food. The Americans were also supplied with sweets and even ice cream, the latter made in machines brought across the Channel.

For the first few weeks, the biggest absence from the soldiers’ diets was fresh bread. Once supply lines were well established, bakeries sprang up. Rations of tooth-jarring hard tac were replaced by fresh-baked loaves.

The supplies included plenty of cigarettes. Almost everyone smoked. This was the simplest comfort for the armies to provide and easy for men to carry around. Morale was maintained through a steady flow of tobacco.

Ever-Present Danger

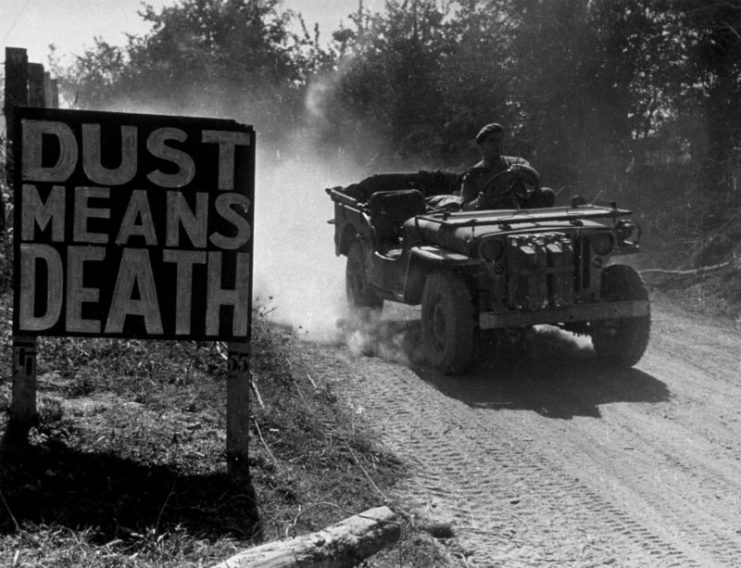

Even away from the front lines, life wasn’t always safe. Though the RAF and USAAF dominated the skies, German planes and artillery occasionally managed to reach past the front lines. One image of the campaign shows a jeep driving past a sign that reads “DUST MEANS DEATH”, a reminder to drivers not to go too fast and so draw attention through clouds of dirt.

For any soldier in Normandy, danger was coming. Though they might rest for a few days away from the front, sooner or later they would be sent into the fight. They enjoyed the moments of calm, boredom and all, and waited for the order to come and send them back to war.