September 1939 is mostly remembered for the German invasion of Poland, the event that triggered the Second World War in Europe. But Germany wasn’t the only power that invaded Poland that month. The Soviets were also on their way.

Propaganda Preparations

Germany and the Soviet Union were unlikely allies. Hitler’s Nazi ideology included repeated condemnation of Communism. The Nazi party itself gave capitalist businesses the sort of free hand that Communists detested.

But as the Second World War repeatedly showed, realpolitik could be more powerful than ideology. The two countries secretly agreed the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, a deal in which they would divide Poland between them along a pre-agreed border.

When the Germans invaded Poland at the start of September 1939, the Soviets didn’t immediately react. They were dealing with a conflict with Japan on their eastern border and needed time to mobilize.

On the 15th of September, Soviet troops began massing along the Polish frontier. Officers were gathered for briefings on the coming campaign. These briefings weren’t just about practical plans for the invasion but also contained a large propaganda element. According to commanders, this would be not an invasion but a liberation, freeing the Polish workers from the unjust rule of the landowners.

On the 16th, commissars went out among the men, providing more of the same briefing. The plight of the Polish workers, including their starvation and torture by landowners, was depicted in lurid detail to fire the men up to fight.

First Clashes

On the 17th, the invasion began. At five in the morning, mechanized cavalry crossed the frontier, soon followed by the rest of the army.

The Poles were poorly prepared for a Soviet invasion. The Molotov-Ribbentrop pact was a secret, while the threat from Germany had been clear for months. Most Polish forces had been focused in the west even before the Germans attacked, and the fighting there had drawn more troops away. The eastern border was poorly defended.

The Polish army was large and courageous, but it was already dealing with the chaos of the war in the west. As the massed forces of the Red Army advanced, they swept all before them. Defensive positions were quickly overcome. Polish troops were captured or brushed aside, inflicting only minor losses on the invaders.

During the first day, the Soviets advanced up to 60 miles. It wasn’t long before Eastern Poland was theirs.

A Ragged Army

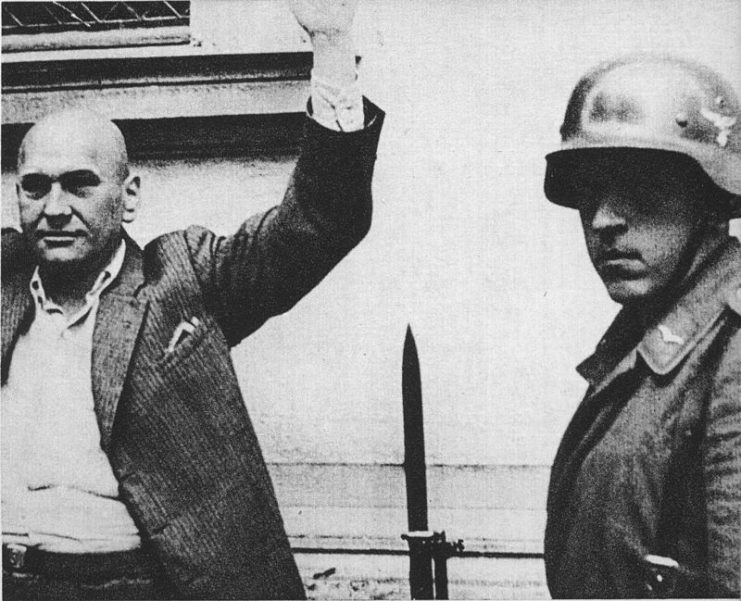

At the sound of rumbling tanks and tramping boots, Poles emerged from their homes, frightened and bewildered, to see what was happening.

What they saw was less than impressive. Many of the Soviet soldiers were carelessly dressed or missing parts of their uniforms. Rear units trailed out along the roads. Supply services were poorly organized. Tanks, tractors, and other vehicles had to be left by roadsides due to lack of fuel.

Far from finding impoverished peasants, the Soviet troops found a country apparently wealthier than their own. Twenty-five years later, Colonel G. I. Antonov still remembered troops disobeying the orders of their superiors to rush into shops and buy everything they could, making the most of a favorable Soviet-set exchange rate.

Dispirited Polish civilians, unable to resist, could only accept this sudden upheaval.

Confrontation

Within days, the Soviets were approaching the new border they had agreed with the Germans for the division of Poland.

Before the invasion, the Soviet troops had been ordered to avoid fighting with the Germans when they met them, settling any disputes peacefully. But as they drew close to the German lines, there were inevitably clashes. Both armies were in a war zone, facing unfamiliar forces. If shots were sometimes fired before questions could be asked, confrontations could easily escalate.

This led to a number of casualties in the new border region. But officers understood their role in this strange new situation, stepping in to resolve disputes even when their men had been injured or killed.

In places, the Germans had passed the new border and were occupying territory meant to go to the Soviets. This sometimes led to tense discussions before the Germans withdrew, taking portable property with them.

On the whole, the two armies cooperated well. The Germans handed Brest fortress over to the Red Army, then the two forces held a joint military parade in the town.

While small enclaves of Polish troops kept fighting a doomed fight and thousands more followed their government abroad to keep up the fight, the Soviets settled in.

Sovietization

Now began the process of “Sovietization”, transforming occupied Poland so that it could follow the same political and economic model of the USSR. Led by the Soviet Union’s interior ministry, the NKVD, this transformation would bring ruin for many Poles.

Economic change came fast. Monetary reforms saw the Soviet ruble replace the Polish zloty, depriving Poles of their existing wealth. Goods disappeared from the shelves of stores, forcing many to pay extortionate prices on the black market.

Private businesses were closed down, to be replaced by ones run by the government. There was no smooth transition. Instead, people were left without basic necessities like bread while the new systems were put in place.

An investigation by the Central Committee of the Communist Party eventually recognized the existence of a food crisis and moved to tackle it. But the Polish workers the Red Army had come to liberate were still worse off than they had been under the much-demonized landowners.

One Man, One Vote

The greatest symbolic act came with elections to the Supreme Council of the Polish Soviet Socialist Republic, as the region was renamed by the Soviets. After six weeks of intense propaganda, voters found only one option for the first member of the council – Joseph Stalin.

Read another story from us: Blitzkrieg Tactics: Lightning Conquest of Poland

The Soviets had quickly conquered half of Poland, bringing in a ruinous regime. Only when the Germans came again two years later would the Poles learn that things could be even worse.