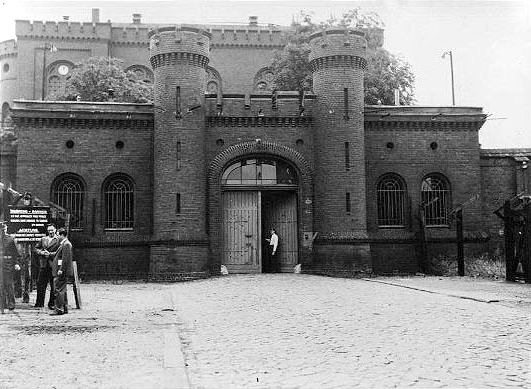

In the borough of Spandau on Berlin’s west side, there sits a shopping complex on Wilhelmstraße that was once a shopping and leisure fixture for the British forces stationed there in the late 1980s. Until 1987, it had been the site of a prison built in 1876 that was demolished, pulverized to dust, and thrown into the sea after the last inmate died in an apparent suicide.

Spandau prison once held those in military detention in the German Empire. After World War I, civilians were also held within the walls. Starting in the 1930s, Spandau prison began holding dissidents, journalists, and many who opposed Hitler and the Nazi Party.

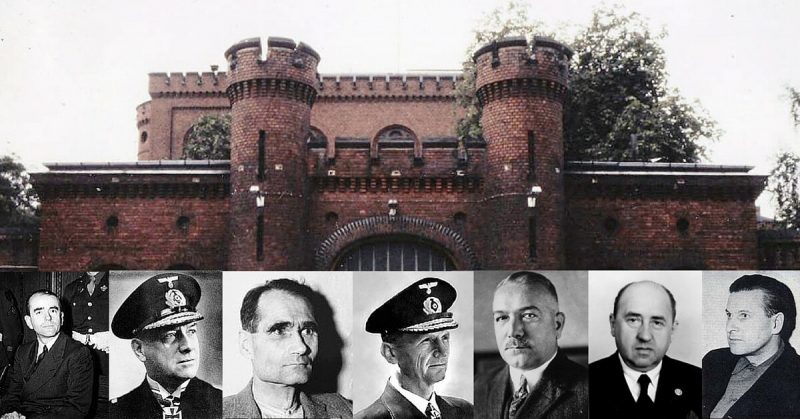

The prison had a capacity of up to 600 inmates, but shortly after the Second World War, it would only hold seven: some of the highest ranking German Nazi government and military officials, sentenced to between 10 years and life in prison.

Management of Spandau prison was an elaborate collaboration between the four powers, Britain, France, Russia, and the U.S. Each country would take one month on a rotating schedule to run the prison for a total of three months each per year. In this way, the prison had four of every official, one from each of the four Allied nations. This dramatic and costly feature was the center of much debate and scorn for the decades in which the prison was operating and especially in its last years when it only housed one inmate.

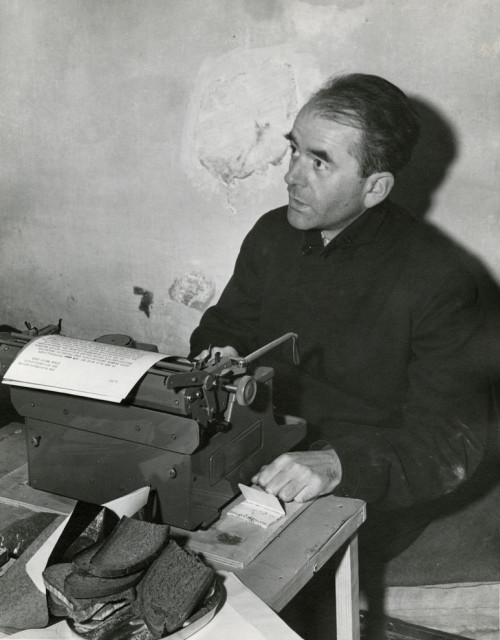

Conditions in the prison were strict, including a ban on any diary or memoir writing, no talking between prisoners and short and scarce family visits. Many guards and officials, especially those who developed relationships with their wards, often bent these rules; the one banning writing, for example, was often not enforced.

But all inmates dreaded the months in which Russia ran their prison. The Russians had no leniency and were far more punitive, not least because Russia had suffered some 19 million civilian deaths during the war.

At least 60 guards, half a dozen machine guns in towers, high walls and barbed wire kept Spandau Prison closed up tight 24 hours a day. And with Nazi sympathizers or those looking to exact revenge on the high-ranking prisoners around, these measures were just as much to keep people out as to keep them inside.

The men who were kept in Spandau prison became known as the Spandau Seven. Some hated each other, some could get along nicely. Some saw a future in politics again and some saw themselves as still the legitimate leaders of Germany. Some lived as fully as they could, accomplishing a lot in their time in captivity and some despised every last minute of it.

1. Erich Raeder

The Grand Admiral of the German Navy, the Kriegsmarine, for the first half of Word War II, Raeder was replaced by his now fellow prisoner, Karl Dönitz. The two argued endlessly about who had lost the war for Germany on the high seas. However, they spent most of their time together, liking the other prisoners even less. During his time served, Raeder was chief of the prison library and Dönitz was his assistant.

Raeder was sentenced to life in prison at the Nuremberg Trials but was released from Spandau Prison in 1955 due to ill health. He died in 1960.

2. Karl Dönitz

Dönitz was the Grand Admiral of the Kriegsmarine after Hitler jilted Raeder. Not only this but from April 30th to May 23rd, 1945, Dönitz was president of Germany, appointed by Hitler before his suicide. Charged with conducting unrestricted submarine warfare at the Nuremberg trials, his case wasn’t decided on this point because other nations, including Britain and the U.S., admitted to the same in many instances.

Dönitz was sentenced to ten years in Spandau prison and released in 1956. During his prison term, he still believed he was rightfully head of the German state.

3. Konstantin von Neurath

Neurath was the foreign minister of the Reich from 1932 to 1938 before Hitler replaced him with one more committed to the Nazi agenda. Later, as Protector of Bohemia and Moravia, Neurath oversaw the suppression of Czech resistance and the execution of students. These details were included in his trial at Nuremberg where he was charged with several counts including war crimes and crimes against humanity.

Arguing that his successor in the office of foreign affairs was far more culpable, Neurath was sentenced to 15 years in Spandau prison, instead of life in prison or death, and was released in 1954 because of failing health. He died two years later. Being a very diplomatic man, he got along with all his fellow inmates better than most.

4. Walther Funk

The former Reich Minister of Economics and head of the Reichsbank was sentenced to life in prison at the Nuremberg trials for, among other things, overseeing the theft of property from Jews in Germany. This even extended to the taking of eyeglasses, rings, and gold teeth from those held in the concentration camps.

Funk was released from Spandau prison in 1957 due to poor health and died three years later.

5. Baldur von Schirach

Schirach was convicted for crimes against humanity at Nuremberg for his part in deporting Jews to concentration camps while Reich Governor of Vienna. He was also the head of the Hitler Youth, but was acquitted on the charge of crimes against humanity related to that. He was sentenced to 20 years and released from Spandau prison in 1966 at the end of his term

He was one of two Nazi officials at the Nuremberg trials to denounce Hitler he also claimed he didn’t know about the extermination camps.

6. Albert Speer

Speer was one of the most ambitious and high-profile Nazis held in Spandau. Hitler’s infamous architect, he also honed the German war machine to its maximum production (which included the use of slave labor) and oversaw the removal of many Jewish families from Berlin.

However, though convicted of war crimes and crimes against humanity, Speer was sentenced to just 20 years, gaining sympathy as the top Nazi to denounce Hitler and his false claim that he knew nothing of the exterminations.

Speer wrote prolifically in Spandau prison, producing a memoir and a book of secret diary entries from his time there. In his 20 years (released in 1966) he also tended the prison garden with his love of design and planning.

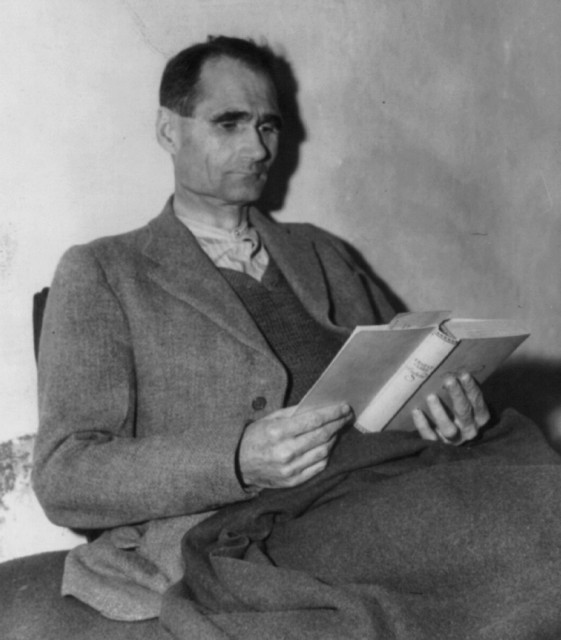

7. Rudolf Hess

Hitler’s Deputy Minister was sentenced to life in prison for crimes against peace and conspiracy to commit crimes. He had been in captivity for several years already, however, after an unauthorized flight to Scotland when he hoped to negotiate a peace with Britain in 1941 and the British arrested him, instead.

Hess was the most detested inmate by his fellow prisoners, besides Speer who often cared for the paranoid hypochondriac. Hess constantly complained of various illnesses and pain. He refused to do “demeaning” work, like weeding the garden. He also refused visits from his family until 1969.

After the release of Speer and Schirach in 1966, Hess was the sole inmate in Spandau until his suicide in 1987. Spandau Prison was then destroyed to prevent it from becoming a neo-Nazi shrine.

Colin Fraser for War History Online