When Japan entered the Second World War, the island nation of Timor was a big target. A small group of Australian, Dutch and British soldiers were tasked with defending it against invasion. While they might have lost the overall battle, the fight they put up was more than the Japanese could have ever bargained for.

Timor was important to the Japanese

Timor, an island nation in Indonesia, was split in half in the early 1940s. The east was controlled by Portugal and the west side by the Dutch. When Japan joined World War II, it was the country’s intention to take control of it.

Portugal remained neutral during the conflict, while the Dutch allied with Australia. Timor became an important part of what the Australian forces called the “Malay Barrier,” which ran down the Malaysian Peninsula. A group made up of British, Dutch and Australian soldiers – called Sparrow Force – was tasked with defending the island and arrived in Timor in December 1941.

The skirmish, now known as the Battle of Timor, began on the evening February 19, 1942, with 1,500 Japanese troops with the 228th Regimental Group, 38th Division, XVI Army landing on Portuguese Timor. That same night, Dutch Timor suffered air attacks, followed by the landing of additional soldiers with the 228th.

Sparrow Force started the battle with around 1,800 troops and fought hard, but they were no match for the number of Japanese.

Sparrow Force faces issues

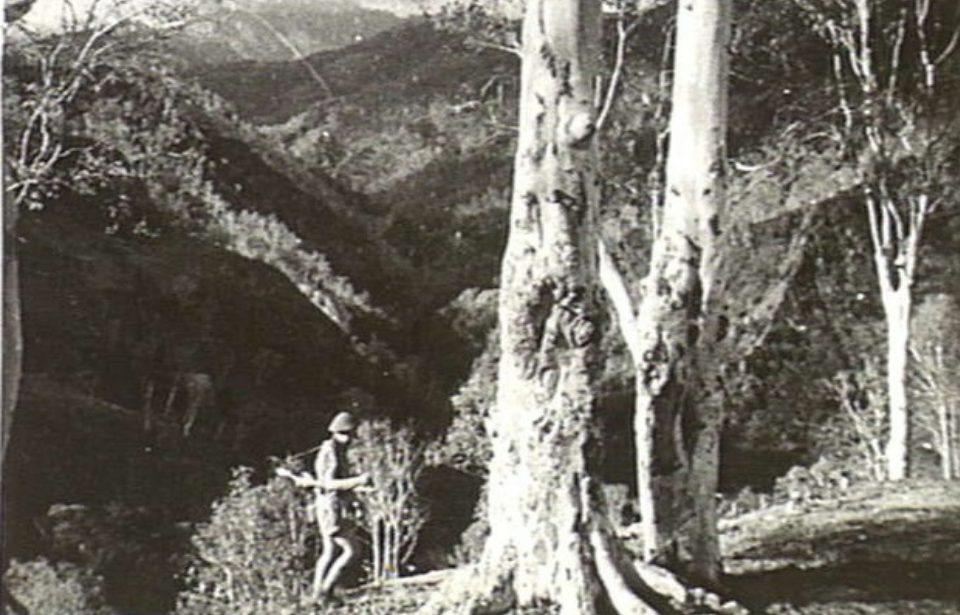

The Sparrow Force HQ team consisted of around 290 men led by Brig. William Charles Douglas Veale. The team began marching east, aiming to meet up with the 2/2nd Commando Squadron. The 2/2nd was especially suited for the upcoming operation and was trained to conduct commando operations. The squadron also had its own engineers and signalers.

The Japanese had taken over much of Dutch Timor, and the Australians had been cut off from communicating with the mainland. The commandos did have one thing going for them: the support of the local people. They were sympathetic to the Allies and allowed them to use their telephones to communicate with each other. Timorese mountain guides also aided troops in planning raids against the Japanese forces.

Through honorary counsel David Ross, the Japanese requested an Australian surrender. This was rejected. Ross also sent a note from the Australians, letting the natives know they would be reimbursed for anything they provided to the troops.

The fighting on Timor continues

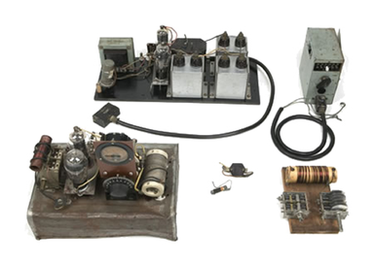

In March 1942, Veale and his men were able to meet up with the 2/2nd. The engineers in these two groups constructed a radio, which they called “Winnie the War Winner.” It allowed them to finally make contact with Darwin, an Australian military base. Soon after, supplies were airdropped to the troops on Timor.

The Japanese grew increasingly anxious about Sparrow Force and the effect they were having. They sent a well-regarded veteran of the Battle of Singapore and the Malayan Campaign, nicknamed the “Tiger of Singapore,” to take them out. However, he was killed by an Australian sniper. After another 24 soldiers were killed, the Japanese pulled back.

Supreme Allied Commander in the South West Pacific Area Gen. Douglas MacArthur and Allied Land Force Commander Gen. Thomas Blamey discussed the possibility of sending more troops to Timor, but decided it would be too much of an investment. It would require an amphibious assault and the use of at least 10,000 personnel, which the Allies couldn’t risk diverting.

Australia pulls out of Timor

The Japanese began to turn the tide in November 1942. One key method they used was pressuring the Timorese and Portuguese people into helping them. They did this largely through threats. The plan worked and this, paired with the increasing skirmishes between the commandos and Japanese soldiers, forced Australian officials to begin pulling officers out of the area. By the end of the year, Japan had over 12,000 troops on the ground.

In December 1942, Australia decided it was best to pull all personal from the island. Evacuations continued into the beginning of 1943, with just a small intelligence team known as S Force left behind. They were soon detected by the Japanese and evacuated by the American submarine USS Gudgeon (SS-211).

More from us: Junkers Ju 87Bs Utilized Psychological Warfare Against Allied Ground Troops

While the Japanese were able to take over Timor, at least until their surrender in 1945, Sparrow Force had made an impact. Over the 10 months they were on the island, they’d had killed 1,500 Japanese soldiers, while only 40 of their own commandos had died. The mission also forced the Japanese to keep troops and resources on Timor, rather than in other areas of the Pacific, such as New Guinea.

Winston Churchill would later say of the group, “They alone did not surrender.”