There are few places on earth with a more ominous name than Iron Bottom Sound, of Guadalcanal. It earned its name through the sinking of almost 50 ships over the course of the Second World War.

For the men who served there, it was a constant battleground. During August 1942, it was where a young Coast Guardsman had the most terrifying experience of his life.

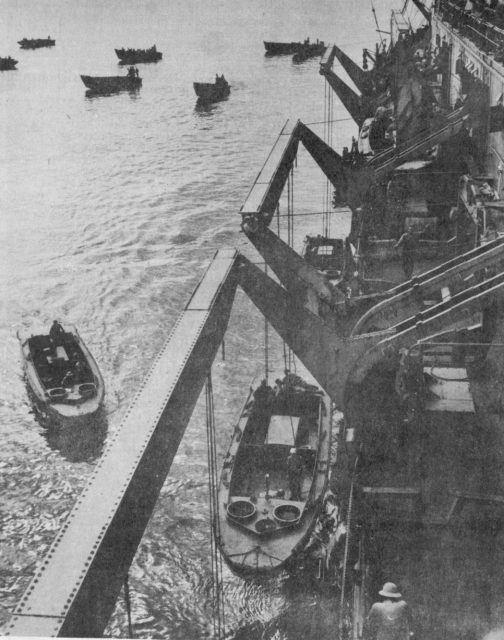

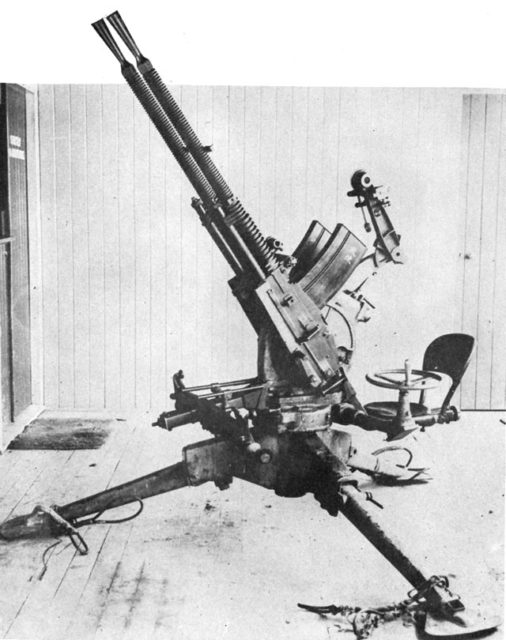

Ten days after American troops landed on Guadalcanal, the situation off the coast was tense, at best. At night, Japanese torpedo boats stalked the waters near Savo Island, and their destroyers continued to harass American transports. To combat this threat, American Sailors and Coast Guardsmen went out in small LCPs, (Landing Craft Personnel), loaded with depth charges and machine guns.

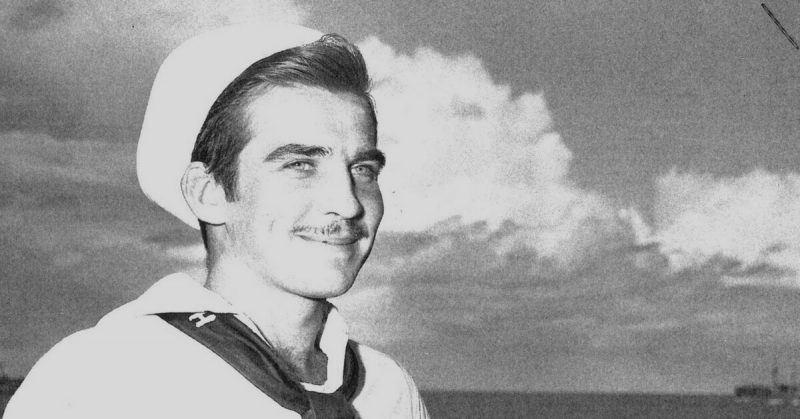

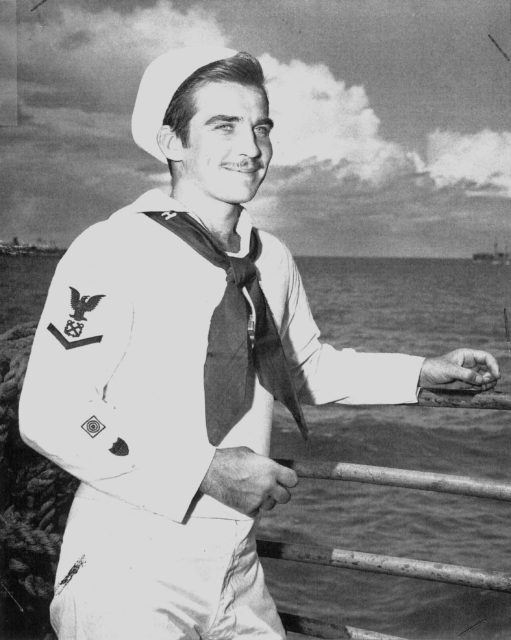

On the evening of August 18, 1942, a young Coast Guard Coxswain, Boatswains Mate 3rd Class Bob Canavan, volunteered to pilot one of these patrols.

He set out with three other Coasties: Boatswains Mate 2nd Class Charles Stickney; Boatswains Mate 2nd Class Charles Williams; Boatswains Mate 3rd Class John Alcorn and two Marines: PFC G. Benson; and Private R. Peterson. Each LCP patrolled a different section of the sound, and Canavan headed to Savo Island.

As the boats pulled away, night enveloped the sound of distant gunfire and could barely be heard over the dull roar of the engines. The six-man crew on Canavan’s craft strained their eyes, peering into the inky black, searching for some speck of light. The night passed peacefully, and the first rays of light crept over the horizon. It was a new day, and it would change Canavan’s life forever.

Silhouetted against the dawn, the young Coxswain saw the outline of a ship. Assuming it was friendly, he approached the vessel, his 36-foot landing craft dwarfed by the almost 400-foot destroyer as it came into clear view. Suddenly Canavan realized he had made a terrible mistake.

Off the stern of the ship, a large flag flapped in the wind. It had a red sphere, with rays emanating out, on a white field; the Japanese Naval Ensign.

Canavan immediately swung his boat about and pushed the throttle all the way forward. It was too late, they were spotted, and the Japanese destroyer Hagikaze steamed towards them. The LCP was barely able to make 8 knots (9 MPH,14.8 Km/H) especially with its heavy load of depth charges. This paled in comparison to Hagikaze which quickly reached 35 knots (40 MPH, 65 Km/H).

Canavan zigged-zagged, hoping to make a harder target for the approaching enemy, but to no avail. The Hagikaze was within firing range, and her machine guns and anti-aircraft guns opened up on the small wooden landing craft.

As bullets tore through the hull, and splinters flew about their heads, they knew they had no choice but to jump. The crew donned their life preservers and jumped off the speeding boat. Canavan ducked down behind the wheel, driving almost blind, but making a smaller target.

Suddenly the wheel went limp; the Japanese had shot out his steering. With all hope lost, Canavan jumped overboard. As he left the boat, he heard rounds smash into the hull where he had been kneeling only moments before.

Canavan had not had time to put on a life preserver, and he immediately started sinking. Swimming below the surface, he re-emerged and then decided to play dead.

The Japanese destroyer circled the small LCP, which was running in a right-hand circle. They shot out its engine, boarded it and removed its machine guns. Then they changed course, back to deal with the surviving crew members.

While Canavan lay limp in the water, the destroyer systematically shot the rest of his crew, all floating helplessly in the inky blue waters of the sound.

Assuming the entire crew was dead, the Hagikaze returned to its mission: bombarding American troops on the shore.

Canavan was now alone, without a life preserver, in shark infested waters, near the bodies of five dead friends. Weighing his options, he considered suicide by drowning but instead he chose to fight for his life.

He swam 12 miles to Florida Island. Over the course of 20 hours, he pushed and pulled himself through the water, fighting hunger, thirst, exhaustion, and the paralyzing fear of discovery. Amazingly he made it.

As he walked up to the beach, his feet were lacerated by the razor sharp coral. He collapsed on the soft sand, immediately passing out. Natives covered him with palm fronds in his sleep. Awaking, he tried to eat a coconut, and drink its milk but his stomach could not handle it, and he threw up. Hungry, exhausted, and in great pain, he kept moving forward, walking across the island to Vatururu point, across from the Marine base on Tulagi Island.

Finally, he reached the small channel between Florida and Tulagi, only 400 yards wide. Attempting to swim this short gap, he was at first pushed back by the strong current.

On his second attempt, he made it across only to find the Marines there pointing their rifles at him. They thought he was an enemy infiltrator. Their commanding officer, not seeing any threat from this exhausted and battered man crawling out of the water towards them, ordered his men to stand down. They hauled him out of the water.

The Marines took Canavan to a nearby field hospital where he recuperated and had his wounds treated. He had just survived the most terrifying experience of his life, narrowly making it out alive. Canavan’s story, however, was not finished.

Shortly after his recovery, he received troubling news. The US Navy had issued his transfer orders out of the combat zone. Canavan was loyal to his officers and crew and did not want to be removed.

Possibly he felt a sense of survivor’s guilt after the loss of five men; three of which were close friends.

He caught wind of an amphibious bomber being transferred to Guadalcanal and saw his opportunity. Stowing away in the storage section of the plane, he disembarked once they reached their destination. He set out in search of his old outfit.

Shortly after arriving, Canavan walked into Commander Dwight Dexter’s office and reported for duty. Surprised to see this crazy young Coastie again, Dexter gave him a thorough reprimand for disobeying orders, but let him stay. Canavan, despite being dropped a rank for going AWOL, stayed on Guadalcanal for the remainder of the campaign.

The Irish-born Coast Guard hero finally passed away at the age of 49 in 1971.