Japan entered WWII with the most diverse submarine fleet of any nation. Some subs were capable of the fastest underwater speeds and were armed with the best torpedoes. Despite this, they actually achieved very little. There was, however, one notable exception.

The Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) deployed midget submarines, purpose-built supply subs and long-range fleet subs capable of carrying planes. Sixty-five of these could exceed 20,000 miles at ten knots – something the Allies couldn’t match. Their 78 midget subs were able to reach 18.5 to 19 knots underwater – making them faster than even the famed German Type XXI at 17.5 knots.

Then there were their torpedoes. The Type 95 torpedo used pure oxygen for burning kerosene – unlike the compressed air and alcohol system used by others. This gave Japanese torpedoes three times more range while reducing their wake to make them harder to detect and avoid.

Finally, there were their explosive systems such as the Type 87 which used a mixture of 60% TNT and 40% hexanitrodiphenylamine – making them even deadlier. As they used simple contact exploders on their torpedoes, they were far more reliable than their American counterparts (which sometimes didn’t explode even when they hit their targets).

The IJN’s weakness lay not in their submarines, therefore. It lay in their military strategy.

Japan won the Battle of Tsushima (part of the Russo-Japanese War) in 1905. Russia’s defeat allowed Japan to begin its occupation of China’s Manchukuo region virtually unchallenged. From that point on, the IJN was convinced that a single, decisive battle was the way to go – making it their official doctrine.

During WWII, therefore, they focused on enemy warships which were faster, better-defended, and more maneuverable. While they did destroy some merchant ships, this was not their primary focus.

Japan entered WWII with 63 ocean-going subs and built another 111. Unfortunately, because their main targets were warships, they lost 128 subs – about three-quarters of what they had.

There was also the matter of waste. Japan couldn’t match the resources or level of industry available to the Allies. During the Solomons and Guadalcanal campaigns, their submarines would sometimes cruise for over a month before finding the enemy, thereby decreasing morale and imbuing the crews with a sense of shame.

Finally, there was the fact that Allied abilities to detect and destroy submarines improved as the war progressed. For many, however, such advances came too late.

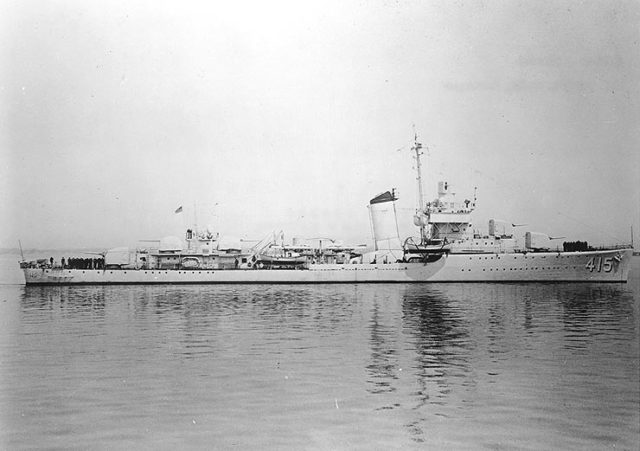

I-19 was a Type B1 submarine. It measured 357’ in length, 31’ at the beam, and 16.9’ at its draught. With its two diesel 12,400 hp engines and 2,000 hp electric motors, it could reach speeds of 23.5 knots on the surface and 8 knots underwater with a range of 14,000 nautical miles at 16 knots.

It was also armed with 6 X 533 mm forward torpedo tubes, 17 torpedoes, and a 1 X 14 cm/40 11th Year Type naval gun. Capable of carrying a 1 Yokosuka E14Y floatplane, the sub had a crew of 94 men.

I-19 was at the bombing of Pearl Harbor – providing support to those doing the bombing. It tried to sink the Panama Express, a Norwegian merchant ship, on December 21, 1941. Fortunately, the ship got away. A second attack the following night on the HM Storey also failed, as did a third on the Barbara Olson on December 24.

The crew of I-19 was dejected until they found the Absaroka later that day. They fired two missiles. The first missed, but the second hit its mark. Before they could do more, however, US Army bombers arrived, forcing the I-19 to retreat.

On March 4, 1942, I-19 took part in the second attack on Pearl Harbor. Its mission was to disrupt the ongoing repair and salvage operations, and to support further attacks on the US mainland in Texas and California.

I-19 lay at the French Frigate Shoals, Hawaii, ready to do its part. As with the first bombing, American codebreakers had intercepted and correctly interpreted the Japanese plans. Although these plans were ignored by their superiors, the Japanese operation failed for various reasons.

On May 26, I-19 was off Nikolski Bay near Bogoslof Island, Alaska, ready to launch its floatplane to search for US military installations when the Americans found it. The sub dove so quickly that its plane was destroyed.

I-19 made up for everything on September 15, 1942. Under the command of Narahara Shogo, it was on a routine patrol south of the Solomon Islands during the Guadalcanal Campaign, when it entered naval legend.

The US Task Forces 17 and 18 were on their way to Guadalcanal, escorting a fleet carrying the 7th Marine Regiment reinforcements. Among these were the USS Wasp, the USS Carolina, and the USS O’Brien.

The Wasp was some 170 miles southeast of San Cristobal Island refueling her planes and being rearmed for antisubmarine patrol operations. At around 12 pm, it launched F4F Wildcats to intercept a Japanese 4-engined flying boat – obliterating it some 15 minutes later.

At 2:20 pm, it launched 26 planes and received 11 more that had been on reconnaissance missions when the Japanese had their revenge. Four minutes later, the I-19 fired six Type 95 torpedoes.

The Wasp’s lookout saw three approaching the starboard (right) beam. The ship turned, but it was too late. Three torpedoes hit, knocking out her power. She was on fire in minutes, forcing the crew to abandon ship.

The other three torpedoes went on. One hit the Carolina on her port side, punching a hole some 32’ X 18” wide and killing five sailors. Despite this, the ship got away.

The O’Brien was also lucky… initially. The crew spotted the smoke from the Wasp at 2:42 pm, so it turned a hard right. Two minutes later, the torpedo missed. They were still watching it move off with a sigh of relief when the sixth torpedo struck her port bow.

The damage seemed superficial, allowing the O’Brien to reach Espiritu Santo, Melanesia for repairs. On October 19, however, her bottom gave out due to the structural weakness caused by the impact, forcing the crew to bail.

With a single salvo of six torpedoes, the I-19 sank three American ships. She would go on to sink two more and damage another in 1943 before she was sunk by the USS Radford west of Makin Island on November 25, 1943. There were no survivors.