WWII was not just fought between regular armies. Wherever the Germans invaded, resistance movements sprang up to defy them.

Backing those groups was an important part of the Allied strategy. In Yugoslavia, where two distinct resistance movements existed under two very different men, a choice had to be made about which to back.

Setting Yugoslavia Ablaze

Early in the war, British Prime Minister Winston Churchill promised to “set Europe ablaze” in resisting the Axis powers. The Special Operations Executive (SOE) was formed to do just that. The secret group stirred trouble wherever they could. They landed agents behind enemy lines, provided supplies to resistance groups, and coordinated with whoever was fighting Hitler.

In Yugoslavia, the SOE turned their hand to intelligence gathering. There, the resistance was divided. Shortly after the German invasion in April 1941, two leaders had emerged, each with their own agenda and ways of working.

Mihailović: The Military Man

Dragoljub “Draža” Mihailović was an ethnic Serb and a career soldier in the Yugoslavian army. He had spent time in postings in other countries as well as commanding troops within Yugoslavia. Shortly before the war broke out, he had run into trouble for criticizing his country’s preparedness for war. In his opinion, the focus should have been less on defending the borders and more on fighting from the mountainous highlands.

At the time of the invasion in 1941, Mihailović was a staff officer. As the Germans advanced, he briefly took command of a “Rapid Unit” before heading into the hills when the Yugoslav High Command collapsed.

Mihailović formed a network of Chetnik units. Originally Serbian guerrillas in the early 20th century, the Chetniks were reinvented as the royalist face of Yugoslav resistance, while retaining their Serbian heritage.

Tito: The Communist Rebel

The other resistance leader was Josip Broz, known by his nickname of “Tito.”

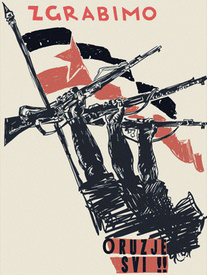

Tito was a committed revolutionary. During the inter-war years, he had been trained in his Communist activities by the Russian government. He served on the Republican side during the Spanish Civil War. Long before the Germans arrived, he was committed to the cause of armed resistance.

A powerful leader, Tito’s nickname came from his tendency to order others to “do this” or “do that,” translated as “tito.”

He reached out to a broader support base than Mihailović. In a country divided along ethnic and religious lines, Catholic Croats, Muslim Bosnians, and Orthodox Serbs all rallied to his cause. His Communist ideology overcame their differences and helped them work together; leading them to a deeper commitment to the Communist cause.

The Political Angle

At first, the British were inclined to support Mihailović rather than Tito. Communism was seen as a serious threat to the British establishment, including its most prominent leader, Churchill. The exiled Yugoslavian King Peter naturally supported the royalists over the Communists. His London-based government-in-exile influenced the Foreign Office and Chiefs of Staff to back Mihailović.

In the early days of the Yugoslav resistance, the British began sending equipment to Mihailović and the Chetniks. Tito had the manpower and the experience of resistance work, but Mihailović now had the weapons.

Hudson’s Mission

The SOE was divided on the issue of Yugoslavia. Its London headquarters was staffed by men drawn from Britain’s mainstream leadership, conservatively-oriented businessmen and bankers. Those based in Cairo, through whom much Balkan intelligence came, had a different outlook. They were more likely to be politically liberal, career military, or both. It led them away from politically-driven support for Mihailović, making them more open to seeing who would really offer the best resistance.

To assist, Captain Hudson, a mining engineer who was fluent in Serbo-Croat, was sent to Yugoslavia in the autumn of 1941. He knew the country well. Hudson met with both leaders and discovered they had been unable to find common ground. The two resistance networks could not cooperate.

Of the two, Tito was much more active in fighting the Germans. It fitted with Mihailović’s stated policy which was that he could do little to resist on his own and must instead prepare to support an Allied invasion.

Following his initial report, Hudson lost radio contact until August 1942, leaving SOE to look at other evidence.

German Signals

Prominent among that other evidence was the interception of German messages which provided information on the German experience of fighting in Yugoslavia. Some of it came from high-level signals. The Allies were careful not to let the Germans know they could read them, so the information was often not widely shared.

What those messages showed was that Tito was by far the more active and effective in fighting the Germans. Far from resisting, Mihailović and the Chetniks were in some cases collaborating with the Germans against the Communists.

In October 1943, the German Supreme Commander Southeast told Hitler that “Tito is our most dangerous enemy.”

Switching Allegiance

In the three-way fight for Yugoslavia, Tito was increasingly looking like the best bet.

In May 1943, Captain William Deakin parachuted into Yugoslavia on another fact-finding mission. It confirmed that Tito was fighting hard while Mihailović was collaborating. At last, practicalities overcame politics, and the flow of equipment shifted from Mihailović to Tito.

Supported by the Allies, Tito continued a campaign of resistance that made him a national hero and allowed him to take control in the post-war era, establishing the Communist government he had sought.

The Allies’ failure to see the truth for years had done nothing to stop him in his work.

Sources:

Ralph Bennett (1999), Behind the Battle: Intelligence in the War with Germany 1939-1945.

Richard Holmes, ed. (2001), The Oxford Companion to Military History.