‘The Raid on Taranto, Italy, 11–12 November 1940’ by Ralph Gillies-Cole. Painting in collection of Fleet Air Arm Museum.

In 1940, the British military situation in the Mediterranean was a tricky one. The Italians and Germans were well supplied in their North African conquests via shipping lanes from Sicily. The British, however, in order to supply their forces in Egypt had to either send cargo the long way around the entire continent of Africa or take the risk of sending convoys via Gibraltar and Malta through waters constantly threatened by the Regia Marina—the Italian Royal Navy.

The British Royal Navy knew they needed to shift the balance of power in the Mediterranean. Their answer to this challenge was a blow to the Regia Marina’s main battle fleet harbored at Taranto (a city tucked inside the heel of Italy’s boot). It was Operation Judgement.

To be clear, 1940 was the year this action was finally considered critical and then taken. British plans to neutralize the Regia Marina in Taranto began way back when Italy invaded Ethiopia in 1935 and the Royal Navy began to fear the loss of their safe shipping lanes in the Mediterranean. In 1938, during the Munich Crisis, the British knew that attacking Taranto had to happen, sooner or later.

The commander of the British Mediterranean Fleet in 1938, Admiral Sir Dudley Pond, was won over by a plan from Captain Sir Arthur Lumley St George Lyster to strike the port with torpedoes and bombs dropped by Fairey TSR Swordfish biplanes. Training began and, when Pound was eventually replaced for command by Admiral Andrew Cunningham, continued until the time came.

The time came in 1940 when France had fallen and Britain lost the aid of their ally’s naval fleet. The tables were turning in the wrong direction.

Interestingly enough, during this time, the Italians managed to stay the top dog in the Sea by keeping their battle fleet in harbor and never provoking a fight. This strategy is known as keeping a “fleet in being.” The idea is that one has a large naval force, large enough to cause concern, but not large enough to just go out and start whatever huge battle one will. Instead, the fleet in being causes the enemy to stay on the defensive, taking huge precautions in fear of the threat.

And the British were doing just that. Shipping supplies through the Mediterranean was more than just a headache. They couldn’t risk totally losing control of the Sea and the Italians couldn’t risk losing their irreplaceable battleships, thus a decisive battle was never sought.

Lyster, a Rear Admiral by this time, commanded the raid that would end this precarious situation on the night if November 11, 1940. Operation Judgement had become a part of the larger Operation MB8, which was mostly focused on escorting several different convoys between British ports, and the Taranto raid, while some ships mounted attacks meant as distractions.

Surveillance planes were flown over Taranto prior to the raid to gather intel. This never caused alarm in the Italians who figured it was in support of shipping convoys trying to avoid the dreaded Regia Marina battle fleet.

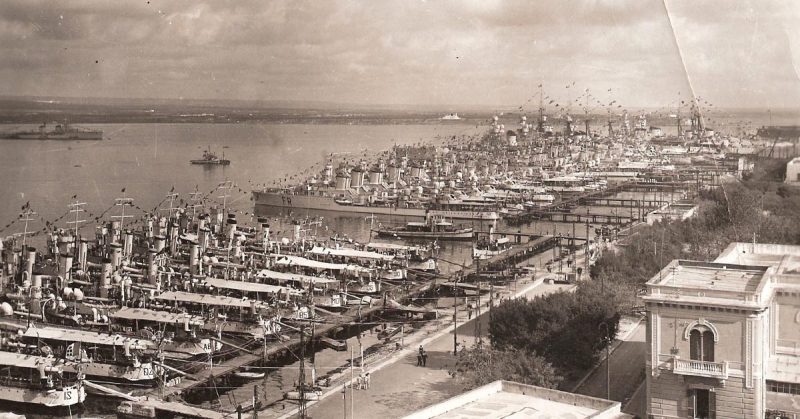

Here’s what the Brits faced at Taranto: The harbor had six battleships, nine heavy cruisers, seven light cruisers and 13 destroyers. There were barrage balloons (fixtures to rebuff low-flying aircraft) and torpedo netting, but neither were near their full, needed deployment due to high winds and continued construction. There were also 101 anti-aircraft guns, 193 machine guns, and flood lights.

The British ships selected for this raid were two heavy cruisers, two light cruisers, four destroyers, and the brand-new, top-of-the-line aircraft carrier HMS Illustrious. On the deck of the Illustrious were 24 Swordfish from the four different Naval Air squadrons.

There had been much concern that an aerial torpedo strike on a harbor like Taranto would be entirely ineffective due to the shallow depth of about 12 meters. The typical torpedo dropped from a plane would need at least 23 meters to avoid hitting the bottom. However, the British had developed a rig to attach on the nose of their aircraft with a wire tied to the nose of the torpedo. This caused the torpedoes to land on the water length-wise, rather than nose-first, for a much shallower dive.

Lyster decided to send out two attack waves of Swordfish (the first with 12, the second with 9), each with planes carrying torpedos and planes carrying bombs. The first wave took off from the Illustrious at 21:00 on November 11, but one plane suffered a failure in its fuel tank and the pilot had to turn around.

The remaining 11 planes struck Taranto in two groups, the first just before 23:00, right over the mouth of the harbor.

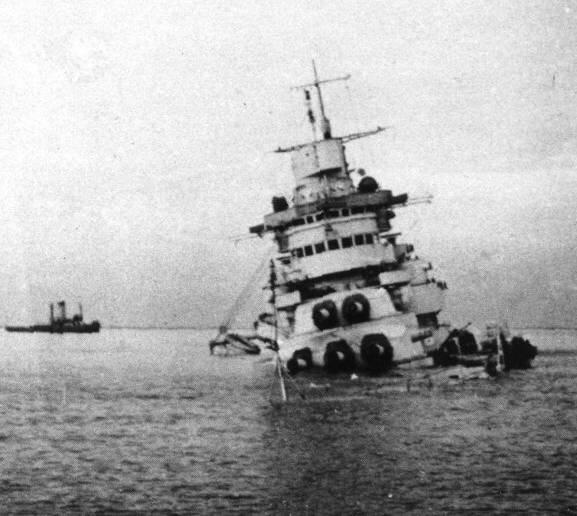

The first group, carrying torpedoes, managed to strike two battleships hard, and the second, carrying bombs, damaged a couple light cruisers and a few destroyers. One plane was shot down.

The second wave of nine Swordfish came over land, Northwest of Taranto at midnight. This wave struck two battleships, one the same as the last wave and one as yet untouched. This wave, too, lost one plane.

The two-man crew of one downed Swordfish was killed and the other pair captured by the Italians, who, strange as it may seem, never used their flood lights (it is easy to assume they might have downed more planes if they had).

The raid managed to disable half the Regia Marina’s battleships. Two were repaired after some months, but one would remain out of commission until it was too late and the Allies had secured control of Italy in 1943.

Admiral Inigo Campioni, Commander of the Regia Marina, quickly moved the remainder of his prized fleet to Naples, on the West coast of Italy, until Taranto was deemed safe to house it again.

Admiral Cunningham had assumed Campioni would be unwilling to engage the Royal Navy after his fleet was so badly handicapped, but was proven wrong just five days later when Campioni struck a shipping convoy bound for Malta.

Though the raid on Taranto failed to decisively shift the balance in the Mediterranean in favor of the British or disrupt Axis shipping to Africa, it did end the Italian’s leisurely strategy of a fleet in being and the naval battle in the Mediterranean began to heat up drastically.

The other fleet in being that this raid would put an end to was that of the U.S. Navy. In the year following the Battle of Taranto, Japanese naval attaches and advisors made several trips to the port city and eagerly used the tactics and results of the raid as lessons for their coming assault on Pearl Harbor, December 7th, 1941.

The Japanese Imperial Navy struck the imposing U.S. fleet with a much larger force than the British had Taranto, launching aircraft from six, massive carriers. The U.S., in turn, had to drastically change their strategy for control in their parts of the Pacific. Instead of a mighty force of battleships, groups of vessels were now based around aircraft carriers, which became the far-reaching fortresses needed for controlling the vast Pacific Ocean.

By Colin Fraser for War History Online