The first naval battle of the Second World War, the Battle of the River Plate was a symbolically important encounter. British ships clashed with a more powerful but isolated German raider off the coast of Uruguay, in a confrontation which proved the truly global spread of the war.

The Ships

The most powerful ship in the Battle of the River Plate was the Admiral Graf Spee, a German Deutschland-class pocket battleship commanded by Captain Langsdorff. The Graf Spee had a top speed of 26 knots. Aside from anti-aircraft weapons, she was equipped with six 11-inch and eight 5.9-inch guns, with a range of 30,000 yards.

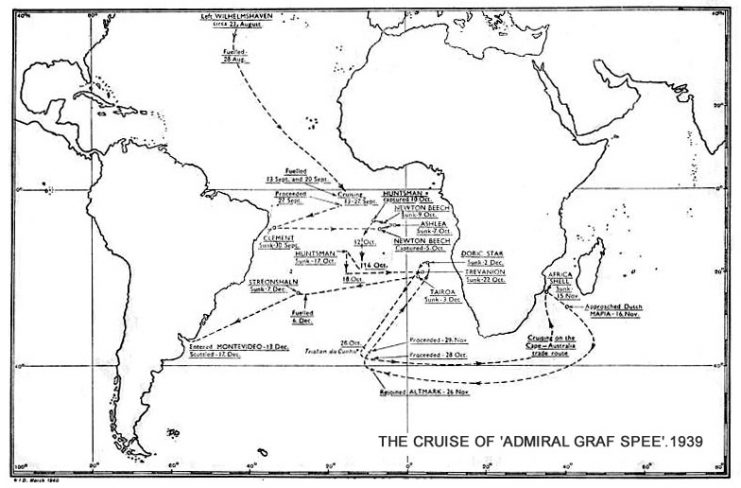

Since the start of the war, the Graf Spee had been prowling the sea lanes, attacking Allied merchant shipping. The British sent several hunting parties to find her. The group that eventually found her consisted of three cruisers – HMS Exeter, HMS Ajax, and HMNZS Achilles, the latter a part of the New Zealand Division. They were commanded by Commodore Harwood.

The Exeter had six 8-inch guns with a range of 27,000 yards. Ajax and Achilles each had eight 6-inch guns with a range of 25,000 yards. All three had a top speed of just over 31 knots.

The British had better speed, giving them an advantage in maneuvering. But when it came to the fight, they risked being outgunned by Graf Spee’s heavier weapons and longer range.

Attacking the Exeter

At 0552 on the morning of the 13th of December, Langsdorff’s crew spotted the masts of the British ships over the horizon. Believing that they would be defending a convoy, he advanced towards them.

On spotting the Graf Spee, Harwood divided his fleet. The Exeter turned left, heading towards the Graf Spee, while the Ajax and Achilles kept their existing course, at a right angle to the enemy. The idea was that the Exeter could provide corrections to the other ships’ aim by spotting where shots fell, even as it engaged the enemy.

At 0617, the Graf Spee opened fire. Within minutes, the Exeter was devastated by the main German guns. The wheelhouse was a wreck, several firing control systems were out, and the captain, though still in command, had been injured.

She had done little damage in response. In one last effort, the captain launched torpedoes, but a turn in the Graf Spee’s course meant that they missed. A further barrage from the Graf Spee took out most of the Exeter’s turrets and left her taking on water.

Seeing that the Exeter was no longer a threat, the Graf Spee turned towards the other ships.

Closing In

Even as the Graf Spee turned her guns to find fresh targets, the Ajax launched her spotter plane. This would give the Allied ships better information with which to target their guns.

The Graf Spee hit the Achilles with her guns. The captain and gunnery control team were put temporarily out of action, silencing the New Zealanders’ guns. Meanwhile, the Graf Spee had taken several hits. While none of them did serious damage to the ship, Langsdorff himself was injured and at one point lost consciousness.

Langsdorff now tried to break away. He had engaged unnecessarily in a battle with the Royal Navy but turned it to his advantage in crippling the Exeter. It would be good to escape while he was still ahead.

Harwood pursued, ordering his two functioning ships to head at maximum speed straight for the enemy. They sacrificed the ability to bring all their guns to bear so that they could better get in close and neutralize the Graf Spee‘s better range.

Both sides launched torpedoes. Both commanders, very aware of the danger these represented, maneuvered their ships to avoid being hit.

Pursuit

By 0738, the Allied ships were within 4 miles of the Graf Spee. But though they were hitting the German ship, as far as Harwood could tell, they were doing little damage. For their part, they had sustained heavy damage and were running low on ammunition.

At 0740, Harwood ordered the Achilles and Ajax to turn east, away from the enemy. His hope was to tempt Langsdorff into pursuing and so close the gap. It didn’t work. The Graf Spee kept steaming west and so Harwood turned to pursue once more.

Despite the relatively light damage to his ship, Langsdorff had decided that she was no longer seaworthy, and so was heading for the port of Montevideo. The Achilles and Ajax shadowed him throughout the day, with both sides sporadically firing at each other, to little effect. After nightfall, the Graf Spee finally reached sanctuary in the neutral port. The battle was over.

While the Exeter headed for the Falklands for repairs, the other Allied ships waited out at sea. They had sent for reinforcements, but for now, their duty was clear – keep the Graf Spee trapped in port. Don’t let her run free again.

Aftermath

Now the battle became one of laws, not guns. International treaties restricted the behavior of belligerent warships in neutral ports. British diplomats used those rules to put pressure on Langsdorff while containing him in port. A steady trickle of British and French merchant ships left Montevideo, and the Graf Spee was not allowed to leave until 24 hours after each one had gone, so was effectively trapped. Meanwhile, the British spread rumors of a powerful force waiting nearby to finish the Graf Spee off.

Believing the rumors, Langsdorff decided that all was hopeless. Rather than risk the lives of his men to no advantage, he scuttled the Graf Spee on the 17th of December. Hitler was enraged that a German captain had given in like this.

Langsdorff took his own life in Buenos Aires on the 19th. The survivors of his crew were interned in Argentina, where many settled after the war.

The battle was a major victory for the British and they made the most of the propaganda coup. It caught the public imagination enough for a film of the battle to be made in 1956. The Achilles, by then the flagship of the Royal Indian Navy, played itself in the film.