One of the best-known films about the Second World War is The Longest Day (1962), which centers around D-Day. In a number of scenes, members of the cast, whether they’re portraying members of the French Resistance or German officers, listen to a BBC announcer read off a list of nonsensical statements. Some are genuine nonsense, while others are meant to instruct the Resistance on how to carry out their sabotage plans prior to the Normandy landings.

The BBC‘s messages to the French Resistance in The Longest Day

In one particular scene in The Longest Day, the mayor of Colleville-sur-Mere, France and his elderly mother sit down to eat a meal. He has the radio quietly playing in the background as he gets ready to eat his soup. As the scene progresses, the audience hear the voice of a BBC announcer beginning the nightly broadcast, which occurred virtually every night until the liberation of France between 1944-45.

“London calling with Frenchmen speaking to their countrymen… London calling with messages for our friends,” the announcer dictates, after which he twice repeats a series of seemingly meaningless statements. The first is, “Molasses tomorrow will bring forth Cognac.” The second, “Jean a de longues moustache,” translates to “John has a long mustache” in English.

At that, the mayor springs into action, almost too excited to remember to put away the radio. He then gets together with another man and blows up a series of telephone poles, throwing the Germans into disarray before the Allied invasion.

The Longest Day shows how quickly the French Resistance acted

Other scenes in The Longest Day show audiences the impact of another message – perhaps the most famous of them all. The BBC announcer reads, “The long sobs of the violins… Fill my heart with a monotonous languor.” Upon hearing this, a German general, who, having received information gleaned by informants and from interrogations, believes the message to signify something very important. Despite his concerns, he’s ignored by his superiors.

The film then turns to a scene where a group of French Resistance fighters are caring for downed Allied pilots in a cellar. When the message is broadcast, they suddenly burst into action, retrieving hidden weapons and going on to blow up a bridge. The first portion of the statement featured lines from a poem by Paul Verlaine, titled Chanson d’automne. It indicated the Allied invasion was underway.

BBC broadcast across Europe prior to and during World War II

While many of the messages related to D-Day, others meant something completely different, as life didn’t stop in other parts of France. Some were as nonsensical as they sounded; they had no meaning attached to them and were only meant to confuse the Germans.

The BBC began to broadcast to German-occupied Europe almost immediately following the fall of France. Prior to the start of the Second World War, the public service broadcaster aired its radio shows to its many foreign assets and English-speaking relatives. At the time, it was called the “Empire Service.”

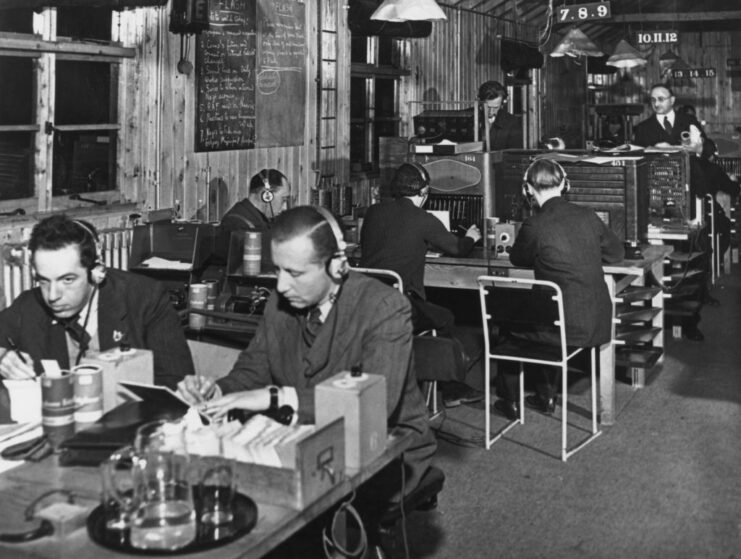

However, just two months after the German invasion of Poland, it became the “Overseas Service.” When the conflict broke out in September 1939, the BBC had 103 employees working on its non-domestic programming. With television broadcasting suspended almost immediately, broadcasters were now the primary source of information and morale. This led the BBC to increase its staff to 1,472 by 1941, a total that only continued to grow until the end of the war.

Radio was still a relatively novel technology

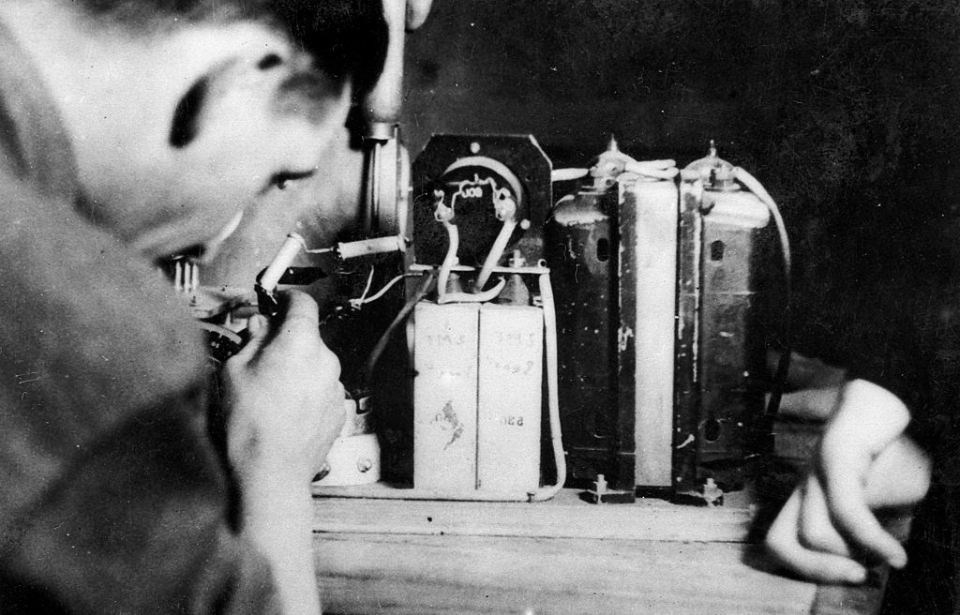

Radio was still a relatively new technology when World War II broke out. Of course, it had served a purpose throughout the First World War, but this mostly involved communications between military units, and it was limited at best. That being said, the time period did see the development of continuous wave radio transmitters and other technology, pushing forward the medium.

By 1939, the BBC and its counterparts in the United States, Germany, the Soviet Union and Japan were able to broadcast across the globe. Politicians, in particular, took advantage of this during the 1920s and ’30s, using radio to reach audiences they hadn’t previously been able to.

Germany used the radio to spread propaganda

The Führer and his propaganda minister were quick to realize the value radio could have in swaying the masses, and soon after coming into power launched a campaign to give cheap radios to every German family. Joseph Stalin did the same in the USSR. Unsurprisingly, both regimes gave out the equipment with pre-set channels on the dial; only government-approved ones were indicated.

In Germany and occupied regions across Europe, listening to Allied broadcasts was a crime. Penalties varied; while first offenses often resulted in just a warning being issued, additional instances saw the issuing of fines and the confiscation of one’s radio. It also wasn’t uncommon for someone to be arrested and sentenced to hard labor, or even given a one-way ticket to a concentration camp.

By 1940, the majority of those living in German-occupied countries, as well as a growing number of Germans and Italians, knew Axis-run radio stations mostly lied to audiences – or, at the very least, exaggerated the information and messages they delivered. As the war drew on and the Axis position deteriorated, a greater number of wounded soldiers with knowledge of what was really going on began returning home, leading more and more Germans to tune into the BBC.

BBC ‘Overseas Service’

The BBC‘s headquarters for both domestic and foreign broadcasts in London was aptly named the “Broadcasting House.” In December 1940, an air raid occurred as part of the Blitz. A landmine exploded, setting the building ablaze.

The foreign broadcast division was sent outside of the city to an unused skating rink. However, it was soon realized that the structure may not be the safest place to be during a German attack, since it had a glass ceiling. Eventually, the BBC Overseas Service settled in London’s massive “Bush House,” one of the most expensive buildings in the world at the time.

Of course, the Overseas Service had broadcasting centers, power/relay stations and antennae throughout Britain and the world. The Far East, Africa and the Middle East were all places where the British and Imperial forces saw action, and the BBC also had stations in Canada, the US, Australia and New Zealand. By the end of 1940, the broadcaster aired shows in 34 languages, with 78 news bulletins, consisting of 250,000 words, being sent out each day.

The Overseas Service was able to do this because it employed native-speaking refugees. While able to speak well in their native tongue, they also had to be bilingual in English and translate their scripts quickly, meaning it wasn’t an easy job. The BBC was also keen to promote the British point of view, not those of the refugees, as many had very different political outlooks to those held by the British government.

Most of the German refugees were Jewish. At first, the BBC refused to put them on the air, as it was thought that any Germans listening would know the announcers were Jewish and not listen. Later, however, a number of German Jews were allowed to speak on the radio, with many employed as writers for the broadcaster’s German programming.

The BBC broadcast messages to Resistance fighters across Europe

The idea to broadcast coded messages was initially thought up by Special Operations Executive (SOE) operative Georges Bégué, who wanted to get messages to other agents without the risk of them being intercepted by the Germans. The SOE was a super secret organization helping to coordinate the Resistance, sabotage and assassination efforts being conducted across Europe.

Returning to The Longest Day, the primary titles of the film involve the first notes of Beethoven‘s Fifth Symphony. These came to symbolize the Allied effort, coming from the observations of Belgian refugee and program organizer, Victor de Laveleye.

Laveleye was the one to realize that British Prime Minister Winston Churchill‘s famous “V” for victory sign could translate in a variety of ways. In French, the word translates to “Victoire,” while it’s “Vrijheid” in Dutch and Flemish. The letter “V” in Morse code is “dot-dot-dot-dash.” The opening of Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony? “Da-da-da DAHH” – virtually all overseas broadcasts began with these ominous notes.

It also wasn’t just the French Resistance to whom the BBC directed their coded messages. In one particular instance, they were broadcast to Poland after the German invasion, with the aim being to inform Resistance members within the occupied country of what was needed of them. They were a minute shorter than others, allowing for a musical message from the Polish government in exile.

How did the French Resistance know the meaning of the messages?

How did members of the French Resistance know the meaning behind the BBC‘s messages? They were relayed by courier on a one-time pad through the SOE. To indicate that a coded phrase was about to be played, broadcasts would start with, “Before we begin, please listen to some personal messages.”

The BBC‘s messages to the French Resistance were typically of the utmost seriousness, and when not relaying information were used to thank agents for their efforts. They were also used to give the impression that something was being planned against the Germans, to divert the enemy’s attention.

In some cases, these messages resulted in some slightly humorous results. “Courvoisier, nous vous rendons visite” translates to “Courvoisier, we’re coming to visit you” in English. The head of the famous brandy-making company, Courvoisier, who lived in London, reported to the BBC and asked about the message.

More from us: POW Camp 198 Was the Site of the ‘German Great Escape’

Another person, a Mme. Courvoisier, also contacted the BBC to ask if it meant her sons, who were being held as prisoners of war (POWs), were returning to France. While intended for the French Resistance, it’s obvious the BBC accidentally targeted the wrong people in this instance.