One of the most important raids in the Second World War was the British raid on Bruneval in occupied France. Its aim was to steal German radar to help the British air force to attack Germany at a critical period in the war.

During WWII, Britain regularly bombed German cities but it was dangerous and costly. The German aerial defense systems were so advanced that British bombers could only attack targets at night. It was, therefore, necessary to obtain a German radar, to enable British planes to fly undetected by German air defenses. That was no easy task either and some scientists believed that it would not be helpful.

Although Hitler originally forbade the bombing of British cities, things changed on 24 August 1940 when German bombers made a mistake. They were only under orders to hit Royal Air Force (RAF) bases, but some went off-course and hit London instead. Churchill retaliated by ordering an attack on Berlin, so Hitler responded with the Blitz – the unprecedented massed bombardment of British cities.

At the start of the war, Germany used radio navigation to guide their planes over military and industrial targets. In response, Britain began jamming and distorting those signals – a period known as the Battle of the Beams. In a time before GPS technology, such distortion also made it harder for German pilots to navigate over Britain. As a result, the RAF had a better chance of downing enemy planes before they could fly back across the channel. This didn’t stop the Blitz, but it made it harder for the German Air Force (the Luftwaffe) to hone in on specific targets. During the Blitz, civilians were the targets.

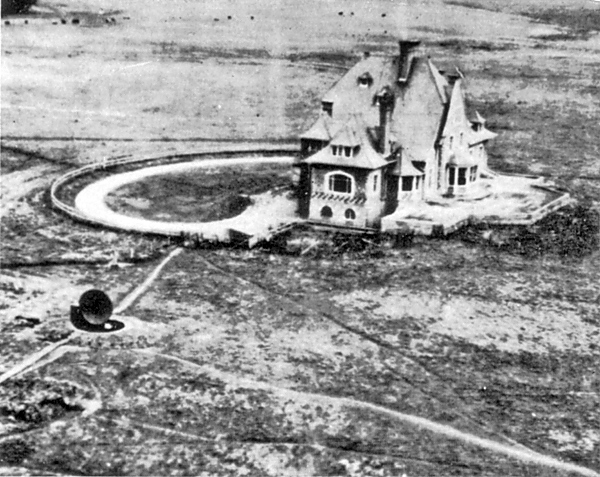

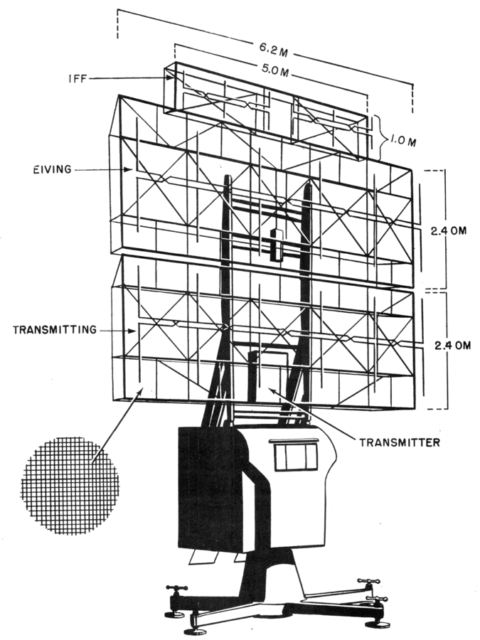

With German cities now under attack, General Josef Kammhuber created a line of search lights and anti-aircraft defenses stretching from Schleswig-Holstein in northern Germany, all the way to Liège, Belgium. These were linked to a radar network along the western European coastline which told the Luftwaffe exactly where to intercept British planes.

As soon as the RAF made it halfway across the channel, radars picked them up. Once they flew over the European coastline, searchlights picked them out for anti-aircraft batteries on the ground. Finally, they had to contend with the Luftwaffe’s fighters.

Dr. Reginald Victor Jones, a physicist with military intelligence, was ordered to crack the Kammhuber Line. He felt certain that radar was the key, but not everyone agreed. Frederick Lindemann, 1st Viscount of Cherwell, was Churchill’s scientific advisor and friend. Lindemann didn’t believe the Germans had sophisticated radar technology, so he ignored Jones’ claims.

Though a respected scientist, Jones was from an ordinary background, while Lindemann was a nobleman who had Churchill’s ear. In a Britain where class hierarchies mattered, Jones was literally outclassed. But as British casualties rose and RAF bombers suffered heavy losses, Churchill finally listened to Jones.

Jones believed that the Germans had used radar as early as 1940 when they invaded France and used it to employ a British destroyer in the English Channel, but he had little proof. By 1941, things had changed. Information from German POWs and the decryption of German secret communications gave Jones’ argument greater weight.

Bletchley Park (which cracked German communications) gave the final clue and proved Jones right. The Germans kept talking about Heimdall – watchman of the Nordic gods who could see by day and night. They also spoke of Freya – the goddess whose jewelry Heimdall guarded. Jones believed these were codes for a radar system. More decoded messages revealed the presence of such a system just outside Bruneval, a village in northern France.

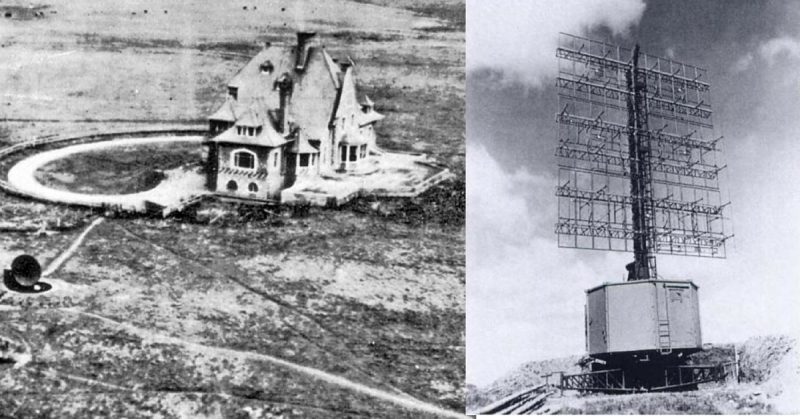

On 5 December 1941, an RAF Spitfire took aerial reconnaissance photographs of the area, revealing a strange, dish-like object beside a cliff. Jones believed it could be the radar he was looking for, but he needed to study it.

So the British decided to steal it. A naval attack on such a heavily-defended site would be suicidal, however, so they chose another option. The RAF had been experimenting with a new parachute regiment called the 1st Airborne regiment. Using paratroopers was new, but Admiral Lord Louis Mountbatten felt it would limit casualties. He also wanted to know if it the parachute regiment was effective.

Aerial photos and information from resistance movements in France allowed the regiment to train on ground which was similar to Bruneval. The plan called for five groups to parachute into the area. The units were called Jellicoe, Hardy, Drake, Nelson and Rodney. One unit would secure the beach. Three units would secure the radar site and take it apart, while the fifth unit was held in reserve. Once they seized the radar, the paratroopers would head to the beach and be picked up by the Royal Navy.

Operation Biting (also called the Bruneval Raid) began on the evening of 27 February 1942 when twelve bombers took off from RAF Thruxton beneath a full moon. Enemy flak met them off the coast of France, but they flew high and avoided getting hit. Then the five groups of forty men made their drop.

All the groups, except the group named Rodney, made it to their landing sites and the attack began. Dismantling the radar was not easy because of heavy enemy fire, so Flight Sergeant CWH Cox (the radio mechanic in charge of dismantling it), just ripped out what he could, hoping the scientists could figure it out. Fortunately, the Rodney group finally reached them. With the Germans overwhelmed, the four groups made it to the beach the next day at 2:15 AM.

But there was a problem. The Nelson unit had secured the beach, but the navy wasn’t there. Off at sea, Commander FN Cook of the Royal Australian Navy was delayed because of two German U-boats. Up on the cliffs, German reinforcements were firing down on the men and more were on their way.

Just before 2:30 AM, Cook’s ship finally the reached the British paratroopers and began firing on the German positions. However, now the men on the beach were trapped between enemy fire from above and friendly fire from out at sea. Fortunately, the Germans retreated because of the British ship’s shelling.

The paratroopers got the radar back to Britain at a cost of two dead, two left behind, with another six missing. The captured two German POWs, one of whom had operated the radar which the Germans called the Würzburg system.

In response to the attack, Hitler ordered that all radar installations were to be protected with barbed wire – making them stand out even more from the air. It also made it easier for them to be spotted by planes from the sky and easier to attack.

The raid was regarded as a great success. It raised British morale and was widely reported in the newspapers. The radar seized also gave the British valuable technical knowledge and allowed British bombers to avoid German air defenses and to limit their losses on air raids over Europe.

The raid also inspired the British to launch other special operations throughout the war. The Bruneval Raid is little remembered today but was of truly great importance to the history of the Second World War.