What was it like to land on D-Day in the deadliest place? Over many years, I’ve read a fair few accounts of the hell that was Omaha Beach, where more than nine hundred Americans were killed on 6 June 1944.

While researching my new book, The First Wave, timed for the 75th anniversary of D-Day, my jaw dropped when I discovered the story of First Lieutenant Robert Edlin, a 23-year-old platoon leader from Indiana in Company A of the famed 2nd Ranger Battalion.

His story of how he survived D-Day – only just – is by far the most dramatic and vivid I have come across.

Edlin arrived on Dog Green sector of Omaha Beach, where from the first wave of some 180 men in A Company of the 116th Infantry Regiment more than a hundred were killed. His own Ranger unit also suffered very high casualties. Indeed, the sector of Omaha fronting the D-1 draw was the most fatal of the eight assigned to the US invaders.

As Edlin closed on the beach, his landing craft got stuck on a sandbar some seventy-five yards from the waterline. “We had hoped for a dry landing,” Edlin remembered. “I told the coxswain, ‘Try to get in further.’ He screamed he couldn’t. That British seaman had all the guts in the world but couldn’t get off the sandbar. I told him to drop the ramp or we were going to die right there.”

“We had been trained for years not to go off the front of the ramp, because the boat might get rocked by a wave and run over you. So we went off the sides. I looked to my right and saw a B Company boat next to us with Lt. Bob Fitzsimmons, a good friend, take a direct hit on the ramp from a mortar or mine. I thought, there goes half of B Company.

“It was cold, miserably cold, even though it was June. The water temperature was probably forty-five or fifty degrees. It was up to my shoulders when I went in, and I saw men sinking all about me. I tried to grab a couple, but my job was to get on in and get to the guns.

“There were bodies from the 116th [Infantry Regiment of the 29th Division] floating everywhere. They were face down in the water with packs still on their backs. They had inflated their life jackets. Fortunately, most of the Rangers did not inflate theirs or they also might have turned over and drowned.”

Time to sprint, run for your life, thought Edlin. Make for the seawall, at the base of the D-1 draw leading up to Vierville.

Move or die.

Men who still breathed were pinned down, cowering behind obstacles like ruined vehicles.

The constant whine of bullets sounded like a maddened beehive. The cold morning air buzzed with death.

Edlin shouted at men who were paralyzed by fear.

“You have to get up and go! You gotta get up and go!”

They refused to move – to save themselves. They were beaten, exhausted, broken teenagers, screaming for their mothers if they could speak at all.

No time to help. No time to stop.

Move or die.

No shelter. No bomb craters. Nowhere to hide. Mines still attached to so many obstacles.

The bombers hadn’t touched a single thing.

Not a goddamn scratch on a single piece of wire.

Not far to go. Thirty yards to the gray seawall, the first place any man had a chance to lay down and maybe live.

Twenty yards. A few seconds more….

Edlin was hit – a sniper’s bullet shattered the bone in his right leg.

Well, I’ve got a Purple Heart.

Edlin fell to the sands. “It was like a searing hot poker rammed into my leg. My rifle fell ten feet or so in front of me. I crawled forward to get to it, picked it up, and as I rose on my left leg, another burst of I think machine gun fire tore the muscles out of that leg, knocking me down again. I lay there for seconds, looked ahead, and saw several Rangers lying there.”

One of Edlin’s fellow Rangers was a large guy called Butch, from Wisconsin.

“Get up and run!” screamed Edlin.

Move or die.

The man was too badly wounded to move.

“I can’t.”

Edlin pulled himself to his feet somehow and tried to reach the man from Wisconsin. “I was going to kick him in the [butt] and get him off the beach. He was lying on his stomach, his face in the sand. Then I saw the blood coming out of his back. I realized he had been hit in the stomach and the bullet had come out his spine and he was completely immobilized. Even then I was sorry for screaming at him but I didn’t have time to stop and help him.”

Well, that’s the end of Butch.

Now the pain was excruciating. He fell to the ground and began to crawl, collapsing after a few yards, blacking out for a few minutes, coming to, close to the seawall. Conscious again, he recognized a sergeant, called Bill Klaus, at the seawall.

Klaus had seen him and he was crawling under rifle fire, the steady stonk, stonk of German mortars firing…still Klaus moved toward him and then pulled him over the sand to the protection of the wall, saving him, just in time.

No man escaped injury. So it seemed on Dog Green on Omaha on 6 June 1944. Klaus had also taken one in the leg and Edlin saw a medic jack him with a morphine spike, and then he gave Edlin a jab too. Could the medic put the jab in the left leg? It hurt most.

Didn’t matter where he put it, the medic said. It would still work.

How about a second shot of morphine – just one more – for the other leg?

No such luck. Too many other wounded to waste precious morphine on him.

Edlin saw other Rangers nearby. They had to get away from the beach.

“You have to get off of here! You have to get up.”

Finally, Edlin was off the beach and found cover in some bushes behind a house. “There was a round stone well with a bucket and handle that turned the rope. It was so inviting. I was alone and I wanted that water so bad. But years of training told me it was booby-trapped.”

He looked up at the top of the bluffs above Dog Green sector of Omaha Beach, where so many men had been killed, including nineteen men from Bedford, Virginia – the so-called Bedford Boys.

Edlin knew he had to keep moving to stay alive. He had to get up, away from the bluffs, out of the range of German guns.

I can’t make it on this leg.

Where had everyone gone?

Had they all quit?

A Ranger shouted nearby.

“Come on up. These trenches are empty.”

Were they? Who knew?

German fire…a machine gun…that by now familiar metallic stutter.

Oh God, I can’t get there!

The steady bark of an American Tommy gun.

The trenches had not been empty.

An angry voice.

“Damn it…they’re empty now.”

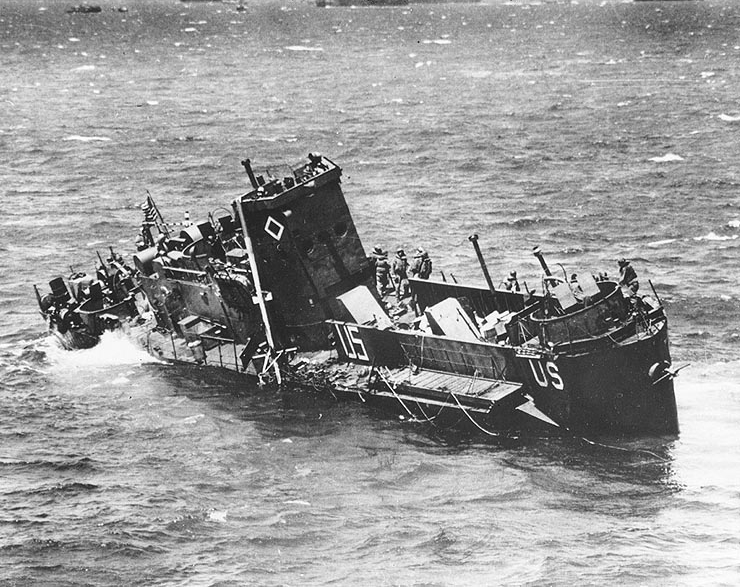

Edlin looked down at the sands, the bloodiest on D-Day. At the cold seas, washing against the scuttled and burning landing craft, and the jagged obstacles. At the stiff and already bloating bodies with blue and gray patches on their shoulders, bobbing solemnly in shallows.

“There were no reinforcements. I thought the invasion had been abandoned. We would be dead or prisoners soon. Everyone had withdrawn and left us. Well, we had tried. Some guy crawled over and told me he was a colonel from the 29th Infantry Division. He said for us to relax, we were going to be okay.”

Men were starting to get off the beaches, the Colonel said.

Some of Edlin’s fellow Rangers had moved inland.

“You’ve done your job,” the colonel told Edlin.

“How?” asked Edlin. “By using up two rounds of German ammo on my legs?”

Edlin was evacuated to England and rejoined the Rangers that July, fighting with great courage and distinction in Brittany. On September 9, 1944, according to one report, “Edlin led one of the most amazing assaults of the war by sneaking a small patrol into the most powerful fortress on the Brest Peninsula.

At great personal risk, he forced a captured officer at gunpoint to lead him to the fortress commandant whom he threatened with a live grenade to surrender the fortress; this ultimately resulted in the capture of over 800 German soldiers and caused a cascading of surrenders throughout the area.”

Lieutenant Colonel James Earl Rudder, commander of the 2nd Ranger Battalion, believed Edlin should receive the Medal of Honor for his actions but Edlin was having none of that. Instead, he received the DSC, having insisted on staying with his unit – had he received the highest award for valor, he would have been sent home and reassigned to a new unit.

Edlin fought on and survived bitter combat in Germany. He returned home to marry his high school girlfriend and enjoyed a long and happy life, dying in Corpus Christi, Texas in 2005. He was hailed far and wide as one of WWII’s greatest Ranger legends.