The events of May and early June 1940 were equal parts disaster and Miracle. For France, it was a complete disaster – a total military defeat by Germany and the loss of their country, all in less than two months.

For the United Kingdom and their British Expeditionary Force (sent in defense of France after Hitler invaded Poland and war was declared in September of the previous year), the rescue of over 300,000 troops from the shores of Dunkirk, France, where the encircling German army was coming down fast and heavy to destroy them, was nothing short of the miracle that kept their hopes for eventual victory alive.

The Prime Minister at the time, Winston Churchill, had to remind people in his famous We Shall Fight on the Beaches speech, “wars are not won by evacuations.” Yet the mere success of rescuing most of their army – not to mention a fair portion of French troops as well – from the unprecedented onrush of German Blitzkrieg felt like victory – and yes, the battle would go on.

How had this happened? The formidable alliance of the UK and France wielded enough troops, technologies, and defenses to never imagine that a German assault could wipe aside all resistance in a matter of weeks. It was a new age of warfare, and they weren’t yet prepared. The Evacuation of Dunkirk was the only saving grace that gave the alliance time to learn the new game and push back against Hitler. For for the next four years, the Nazi flag flew over much of Western Europe, with the Western Front pushed into the sea.

Between the British Commonwealth forces, the French army, and those of Belgium, Holland, and Luxemburg, troops preparing to take on the Wehrmacht in the West numbered well over three million (not including French troops gearing up for fighting Italians in the South). But Hitler had soldiers to match, not including the ones still engaged in Poland, Denmark, and Norway.

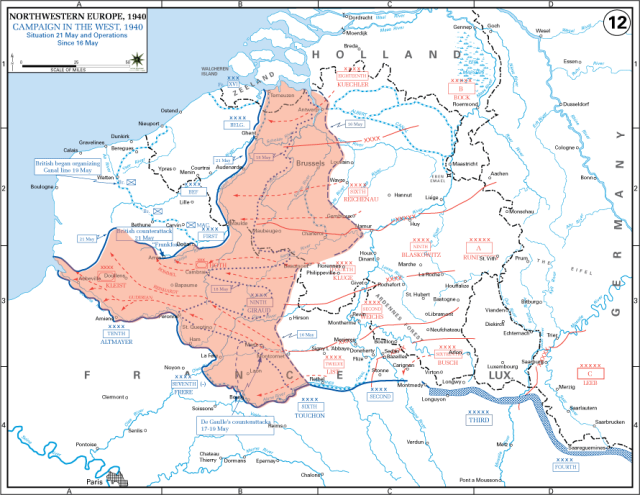

The French had constructed the famous Maginot Line to defend their border with Germany and considered the Ardennes region to the northwest to be too heavily forested to risk moving an army through only to be met on all sides when marching out of it by the full force of several French armies. Along with these defense tactics, and the added might of the BEF and their Belgium neighbors would surely lock the Germans in a prolonged and costly ground battle before barely pushing into France.

However, the French had prepared for another war based around infantry and artillery, like the First World War. Though they possessed an impressive array of large guns, their weapons for fighting tanks and aircraft were not nearly sufficient. As German troops poured through Holland, Luxemburg, and Belgium beginning on May 10th 1940, and into the Ardennes, the French couldn’t match the Luftwaffe’s air superiority.

By May 16th, Germany had punched through the Ardennes and well into France. Three Panzer Divisions were sent to secure the Somme River and raced along it, reaching the English Channel just a few days later. Blitzkrieg had swept aside the French armies and by May 21st they had cut off French First Army, the BEF, and the Belgium army, with their backs against the sea.

In a decision which has been debated ever since by historians and military strategists (and certainly in German high command during the rest of the War), Hitler and the Wehrmacht ordered a halt to the German advance on May 22nd. Though this gave the Allies time to regroup and prepare what defenses they could, it took away the German concern that they were advancing too fast to retain their supply chain and were leaving forward troops vulnerable to counterattack until reinforcements arrived.

On the 27th and 28th of May, King Leopold and the Belgium Army surrendered, putting the full weight of German Forces on the BEF trying to secure the coast and the French First Army, which was further inland at Lille, trying to keep their forward position until everyone could retreat to the sea.

By this time, the British cabinet was already debating the evacuation of the BEF, though they avoid including the French government in their deliberations so as not to give their ally the impression that they were being abandoned. Thousands of men of the BEF had been forced to surrender Calais on May 26th. On May 31st, after holding off seven German division – including tanks for which they were woefully unprepared – the 35,000 men remaining of the French First Army at Lille capitulated.

Now, the BEF position in Dunkirk was the only real Allied holdout in northwestern France and Belgium. They area had been chosen because it was the most suitable for evacuation.

Churchill ordered Operation Dynamo, the evacuation plan, to begin on May 26th. Though over 28,000 men had been returned to Britain already, it was clear on the first day of Dynamo, when only 7,669 men in total were taken from Dunkirk, that they were going to need more than the British Royal Navy if they were going to save the BEF.

While the Luftwaffe bombed the harbor at Dunkirk, making evacuation even harder, the Royal Navy was requisitioning every craft they could find that was seaworthy and could carry men. Many citizens with boats of their own volunteered and sailed out to rescue men from across the channel. In total, almost 700 British ships were involved in the evacuation. With craft from other Allied nations included, 861 boats ferried men from Dunkirk to Dover and other British ports.

As German forces closed in on the BEF and remaining French troops, General John Vereker, 6th Viscount Gort, commander of the BEF was struggling to supply food and water to all the men. Many were drinking whatever they could find. Though many thousands of men were able to be rescued from the harbor by small craft, many other thousands had to wade out into the sea to shoulder-deep water to wait for hours.

By June 4th, the entire remainder of the BEF was evacuated, over 336,000 men and the vanguard of 40,000 French troops surrendered to Germany. But 68,000 British, alone, had already perished in the fight.

Each day during the evacuation, tens of thousands of British, French, and other Allied troops were returning to Britain. Many thousands of the French troops were soon returned to France, only to be killed or captured as the Nazis swept through their nation. France formally surrendered on June 22nd. Operation Ariel, the evacuation of the second BEF, took place between June 15th and 25th, removing the remainder of British forces from France that weren’t cut off in the northern pocket. They would return on June 6th, 1944, along with U.S. and other Allied troops for the D-Day invasions.

By Colin Fraser For War History Online