As Allied soldiers stormed the beaches of Normandy on D-Day, the 6th of June 1944, others were paving the way for their arrival. The French Resistance, the covert volunteers who had been struggling against the Nazis since 1940, leaped into action. They put their lives on the line as at no other time in the Second World War, risking everything to help the professional soldiers. This was their chance to liberate their country, and they seized it with both hands.

A Covert Army

The French Resistance first emerged following the fall of France in 1940. With the nation’s armed forces shattered, some French people fled to Britain to remain free and continue the war. Most others bowed, with varying degrees of willingness, to the occupiers and the collaborating Vichy regime. But a few took another path, forming cells of spies and guerrillas who kept the hope of a free France alive. They provided intelligence to the Allies, sabotaged German facilities, and smuggled downed airmen and escaped POWs to safety.

The risks were incredibly high, and many Resistance members met horrible deaths at the hands of the Nazi regime. But their numbers kept growing, and by June of 1944, 100,000 Resistance members were waiting to rise up.

Strained Coordination

From the start, the Resistance had received support from elsewhere in the Allied camp. Britain’s Special Operations Executive (SOE), America’s Office of Strategic Services (OSS), and the exiled Free French forces under General de Gaulle had all made efforts to strengthen the volunteer force. They had forged connections with existing Resistance cells, fostered the growth of new ones, and provided them with supplies.

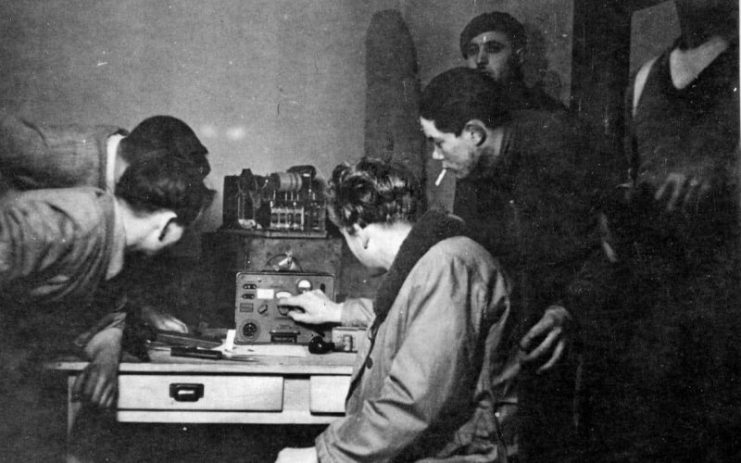

Perhaps the most important support the Allies gave came in the form of radio sets. These allowed the Resistance to more effectively coordinate with the rest of the Allies and with each other. Central to this was Radio London, a propaganda station the Allies used to keep hope alive in Europe. By transmitting pre-arranged code phrases in the personal messages part of its broadcasts, Radio London let Resistance members know about specific events, such as supply drops.

Immediately before D-Day, the Allies sent in the Jedburgh teams; three-man groups of Allied soldiers who were parachuted into France with radio sets. They joined up with Resistance cells, supporting them in their work and bringing them under Allied military leadership.

The Americans and British couldn’t afford to entirely trust the Resistance or even the Free French. Therefore, they kept details of the plans for D-Day from these critical allies until the last minute. In the lead-up to D-Day, signals told the Resistance that something was coming. They were encouraged to launch attacks on specific types of targets to prepare the way. At the start of June, a signal told them that the invasion was imminent, but when and where remained a closely guarded secret.

Operations for Liberation

The Resistance carried out several distinct but related operations around D-Day:

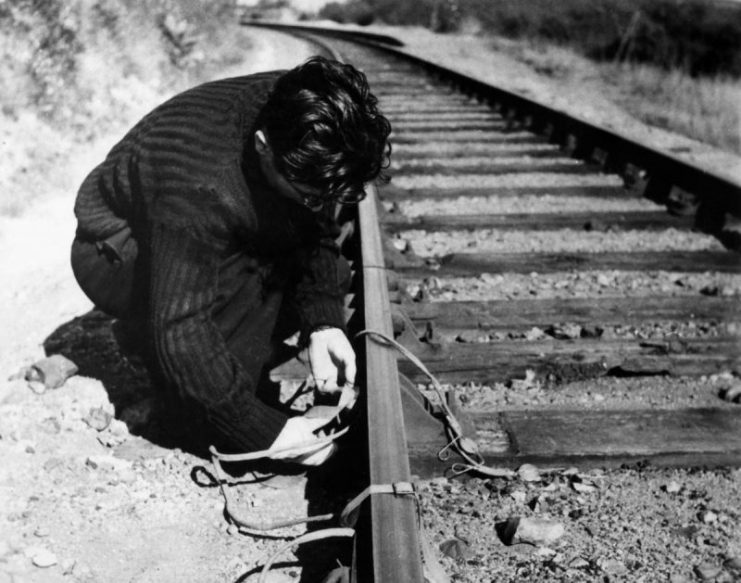

- Plan Vert – sabotaging the railway system.

- Plan Tortue – sabotaging the road network.

- Plan Violet – destroying phone lines.

- Plan Bleu – destroying power lines.

- Plan Rouge – attacking German ammunition dumps.

- Plan Noir – attacking enemy fuel depots.

- Plan Jaune – attacking the command posts of the occupying forces.

Some of these plans went active in the weeks leading up to the invasion. Plan Vert was particularly effective. Together with an Allied bombing campaign, the Resistance destroyed 577 railroads and 1,500 locomotives, three-quarters of the trains available in northern France. As part of Tortue, they also destroyed 30 roads and, again with British bombers, 18 of the 24 bridges over the northern stretch of the River Seine.

These attacks on the transport network were crucial to the success of D-Day. With trains out of action and roads ruined, the Germans struggled to get reinforcements to the front. The work of the Resistance crippled any potential for a significant counter-attack.

The Signal Comes

On the night of the 5th of June, the crucial message arrived from Radio London. The attack was coming.

Now was the time for Plan Violet, perhaps the most important work the Resistance would do around D-Day. Across the country, they sprang into action, cutting phone lines and attacking communications centers. 32 telecommunications sites were destroyed in these attacks.

The Germans used phone lines for communication in occupied France, and the damage made it harder to coordinate their response to the landings. Forced onto radios, the Germans were now communicating through signals that the Allies could intercept. Unknown to the Germans, the Allies could decipher even high-level signals, thanks to the decryption of the Enigma code. And so the Resistance’s work attacking phone lines also revealed German plans to the Allies.

On the Attack

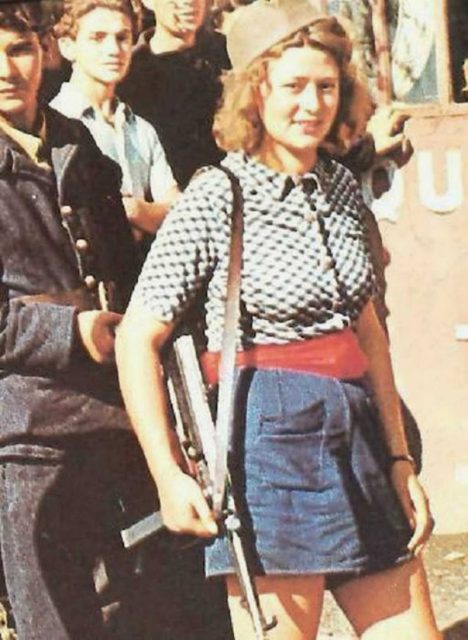

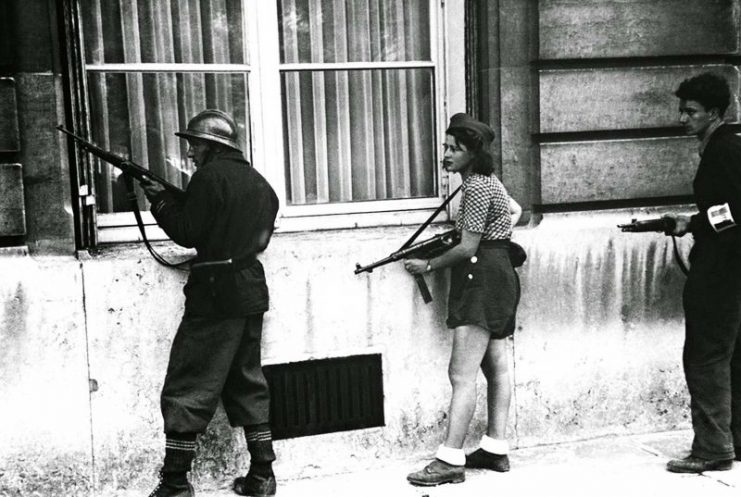

Emboldened by the Allies’ arrival, many Resistance cells went on a war footing. They ambushed German troops heading for the front. In some towns and villages, they killed or drove out the occupying authorities.

Close to the Allied landings, some of these operations were carried out in coordination with the SOE and Jedburgh teams, or with paratroopers who had landed behind German lines. As the regular forces advanced, the Resistance rose up to help and to punish the occupiers who had oppressed them for the past four years.

Unfortunately, this ended badly for some groups. Far away from the newly arrived armies, they lacked the support they needed to survive now that they had revealed themselves. Some of these groups were forced on the run. Others were killed weeks before the Allies could reach them. French leaders encouraged them to stand down and return to guerrilla operations until regular forces reached them, in hopes of saving lives.

When the signal went out from Radio London on the night of the 5th of June, it unleashed a force of men and women desperate to free themselves from the Nazis. Their courage and energy were vital to the success of D-Day, crippling the enemy’s infrastructure and destroying troops destined for the front. Many died in the fight, falling just too soon to see their country freed. But for the 100,000 members of the French resistance, it was a price worth paying.