As the dismal weather of a Balkan winter lashed the streets, German soldiers and civilians lined up waiting a chance to leave. WWII was almost at an end. The Red Army was approaching, bringing death and destruction. The people of Kurland and East Prussia wanted to escape and reach safety in the German heartlands.

It was a slim hope.

Army Group North on the Baltic

As the winter of 1944-5 gave way to spring, Army Group North was in retreat. Repeated Soviet assaults had battered the once formidable German army. Naval and Luftwaffe units had joined the infantry, to provide men to fight on the front lines. Every unit was under strength and undersupplied.

In the face of the rising Red tide, Army Group North retreated toward Baltic ports. They were their sole source of supplies and the only potentially safe route out for Germans trapped in those provinces. For the same reason, they were the target of Soviet advances.

By April 1945, most of the German-held territory along the Baltic had fallen. Army Group North clung on in small pockets around the cities of Libau, Pillau, and Danzig.

No Retreat, No Surrender

Kurland and East Prussia were regions with significant German populations vulnerable to the Soviets. Following WWI, East Prussia became an enclave cut off from the rest of Germany as the land between West and East Prussia was ceded to Poland. Kurland had a mixed population of Latvians and Germans. It had been one of the strongest pro-German holdouts in the war that formed an independent Latvia after WWI. The USSR conquered it in 1940, but then it was seized by Germany in 1941.

Far from Germany’s heartland, the troops were increasingly isolated as the Soviets advanced in the spring of 1945, but they were not allowed to escape. Even after successive poundings at the hands of the Russians, Hitler would not allow the battered army and the German civilians to evacuate. He explicitly rejected such a plan in January 1945. He was determined to cling on.

The Plight of the Refugees

An estimated seven million Germans were hoping to be evacuated from Kurland and East Prussia. As the days went by, hope gradually wore thin for the trapped civilians. The lack of a coherent evacuation plan left them desperate. Following rumors of an evacuation, thousands tried to cross the frozen waters between Pilau and Danzig, but Russian air attacks smashed the ice, and they were drowned.

The Navy made attempts to help them escape, but the Soviets bombed German shipping, shrinking the Navy’s ability to transport people.

The civilians were trapped in a cold and miserable Baltic spring while Russian bombs rained down on their cities. They had been taught to fear the Russia barbarians, and they knew the Red Army was coming.

Koch’s Betrayal

Erich Koch, the Nazi official in charge of the region, condemned those who fled as well as his troops who failed to break through the Soviet lines. Meanwhile, he gathered his possessions, loaded them on two railway wagons, and had them sent back to Germany for safe keeping. Then he and his staff headed to Libau. There, he had two ice-breaking ships waiting to take them through the Baltic to safety. He refused to take refugees with him, showing no concern for the people. He could not see the hypocrisy of his actions.

Königsberg

During the second week of April, Königsberg, the capital of East Prussia, fell to the Soviets.

The Russians promised honorable treatment to the surrendering Germans. Soldiers were told by their officers not to destroy their equipment but to hand it over intact to the Soviets.

What followed reinforced all the fears the Germans had about the Red Army. The Soviets were bitter and frustrated from a grueling war and the atrocities carried out by the Nazis in Eastern Europe. They vented those frustrations on their prisoners. Many were beaten and killed. Others suffered terrible conditions as they disappeared into Soviet prisons for years on end.

Fleeing Danzig

In Danzig, another Nazi governor showed his true colors. Just like Erich Koch, Albert Forster sought to save his own skin. He took his entourage on board a luxury steam yacht and set sail from the port. While his vessel was nearly empty, thousands of refugees waiting for rescue watched him leave.

As Forster’s yacht left Danzig, it passed an old ferry boat overloaded with refugees and struggling to stay afloat in heavy seas. When the yacht did nothing to help, the commander of a German destroyer turned his guns on Forster’s boat. He was obliged to help or risk being sunk. He took the ferry in tow, helping it reach a safe harbor in the west.

Evacuation at Last

Hitler’s suicide at the end of April finally brought a change. Without his opposition, a proper evacuation plan was arranged.

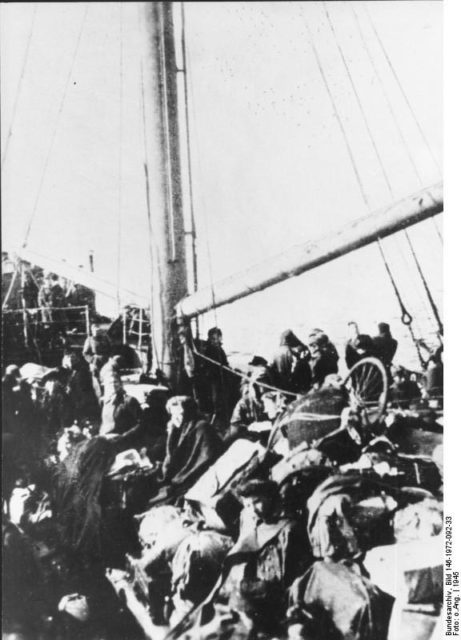

The German Navy made a desperate attempt to get as many people as possible out of the beleaguered territories. Minelayers, minesweepers, torpedo boats, and trawlers shuttled evacuees from isolated spots along the coast to the main ports. Convoys gathered in the harbor at Libau and were crammed full of Germans seeking sanctuary.

They had to be quick. Soon, Army Group North would be compelled to surrender and then all convoys would end. Anyone left behind risked life in a Soviet concentration camp.

By the time it ended, more than 2,000,000 people had been evacuated out of the eastern provinces. Many died along the way as ships were sunk and Soviet attacks pounded German cities. Many more people were left behind.

It was a shameful era for the governors meant to protect the people and for the way those who remained were treated. Some civilians, at least, escaped.

Source:

James Lucas (1986), Last Days of the Reich