The name “U-boat,” an abbreviation of the German unterseeboot which, literally translated, means “undersea boat,” is a name that has become synonymous with swift and deadly attacks from the depths of the ocean, torpedoed Allied warships sinking into the icy waters of the Atlantic after having been taken by surprise, and the most potent submarine fleet of the Second World War.

While the U-boat fleet’s reputation for ruthless effectiveness is generally well known, a fact that is perhaps not so widely known is that these legendary submarines were, ultimately, almost as deadly to their operators and crews as they were to their foes.

By the time the war ended, of the 40,900 Germans who served on U-boat crews 5,000 were taken prisoner and 28,000 lost their lives.

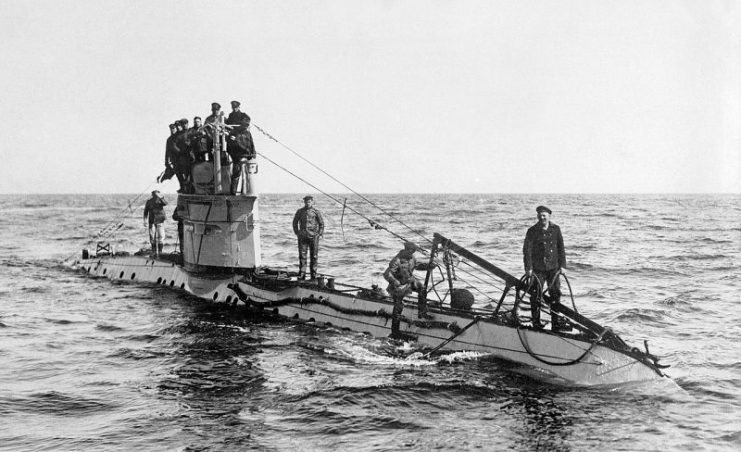

Germany’s history with submarines goes back to the First World War, and they were the first nation to use subs during that particular war.

While their WWI fleet started out with only 38 U-boats – which were small, almost flimsy watercraft, each no larger than 1,000 tons – they proved to be tremendously effective against British warships and later against American merchant vessels, sinking more than 10,000,000 tons throughout the duration of the war.

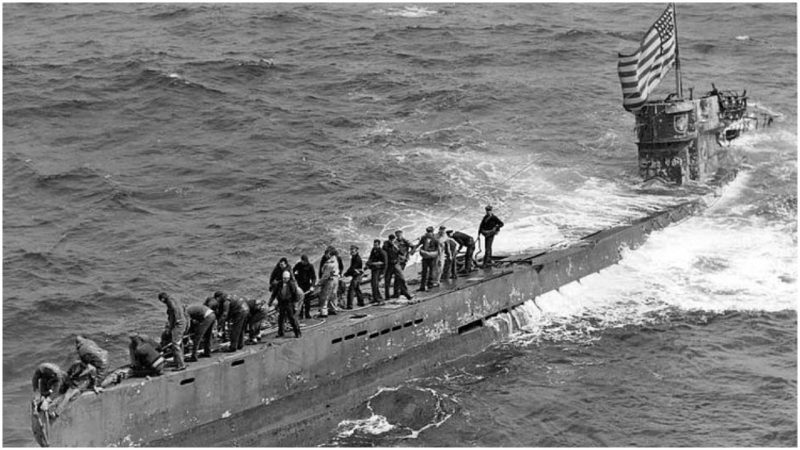

While the Armistice of 1918 forced Germany to surrender its entire U-boat fleet, and the Treaty of Versailles prevented them from constructing any more, the effectiveness of the U-boat fleet was not forgotten by Germany’s military leadership.

Soon after Hitler took power, he made the restoration of Germany’s U-boat fleet one of his priorities. After repudiating the Treaty of Versailles in 1934 and withdrawing Germany from the League of Nations in 1935, Hitler began a program of rearmament. This, of course, included the construction of a fleet of U-boats.

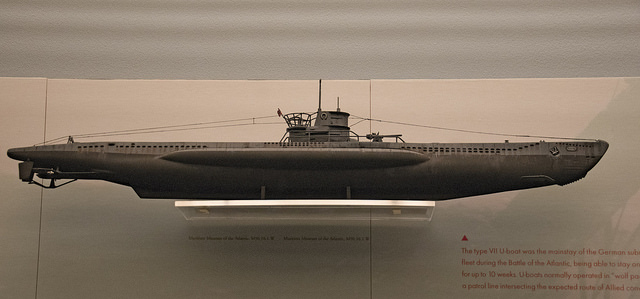

In 1939, when the Second World War broke out, Germany had only managed to construct 57 U-boats, but these new U-boats were far sturdier and more technologically advanced than their WWI predecessors, featuring heat-seeking torpedoes, large gun decks, and spiderweb mines. These 57 submarines were used with tremendous effectiveness against British warships and merchant vessels, which were ill-prepared for undersea warfare.

The U-boat attacks on supply ships transporting goods between Europe and Britain were especially devastating, and if left unchecked could have cut the British Isles off from a great number of vital civilian and military supplies.

During this first phase of the war, each U-boat operated alone. They had to update their tactics when Allied ships began to travel with escorts trained to counter the U-boat threat, as well as Allied airplanes which worked to spot and destroy U-boats from the sky.

To counter this, the U-boats began traveling and operating in groups, which were given the ominous-sounding moniker “wolf packs” by the British. The U-boats also strived to become even more stealthy, surfacing only under cover of darkness, and striking when least expected.

Often one U-boat would shadow an Allied convoy and then, when conditions were ripe for a strike, call in the other members of the “wolf pack” to launch a combined attack.

The Allies soon upped their game, however, and developments in radar technology meant that the U-boats’ potential for stealth became diminished. In addition, the Allies began to develop specific anti-submarine weapons and tactics, and the situation for German U-boats changed quite drastically.

In March 1943 U-boats had almost crippled Britain’s Atlantic supply line, but by May that year the Allies had struck back in force, and 41 U-boats had been sunk – often with their entire crews perishing.

From this point on, German submarine commanders had to revise their tactics, and U-boats largely withdrew from the Atlantic Ocean, operating instead in less populated waters like the Indian Ocean or the Pacific, where unescorted Allied targets could still be found.

There they once again proved effective, but they never again reached the heights of effectiveness they had attained in the early stages of the war.

Life on board a U-boat was uncomfortable for the crew, to say the least. The average deployment time of a U-boat mission could be anywhere from three months to six, and during this time the crew had to put up with extremely adverse conditions.

The living quarters were cramped to the point of being claustrophobic, and essential supplies like food and water were strictly rationed. Often the men of the crew could not even change their clothes for weeks, while the scarcity of freshwater (priority was given to storing diesel instead of water) meant that bathing and shaving were forbidden.

The crews operated on strict shifts of four hours during the daytime and six hours at night, and with space being extremely limited, as soon as one man got up from his bunk, whoever was switching shifts with him would climb straight into it. Only canned food could be taken on board, as anything fresh would quickly be contaminated with diesel fumes or simply rot.

Read another story from us: Predators of the Seas: Life Inside a U-Boat – In 41 Images

In addition to these extremely taxing living conditions, there was the added element of always having to be on full alert, and knowing that a single torpedo strike or bomb dropped from an airplane could result in the death of everyone on board the sub. Not surprisingly, being part of a U-boat crew could wreak significant psychological havoc on a man’s mind.

In the end, while technology made the U-boats so effective at the start of the war, technology was also what ended up putting them out of action.

The Allies kept upping their game against the U-boats, and ultimately, of the 1,162 U-boats the Germans constructed during WWII, 785 were destroyed by the end of the war and the total casualty rate of U-boat crews was almost seven out of ten men. Nonetheless, the name “U-boat” still rings with a deadly authority to this very day.